Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowEven after 45 seniors from Indianapolis Metropolitan High School grabbed their diplomas and threw their mortar boards at a June 4 commencement, they knew they wouldn’t lose touch with their school.

It’s not allowed at Indy Met.

That’s because, for two years after graduation, school officials regularly e-mail, text and visit alumni to see how they’re doing in college. Indy Met teachers even offer to help former students with their college work.

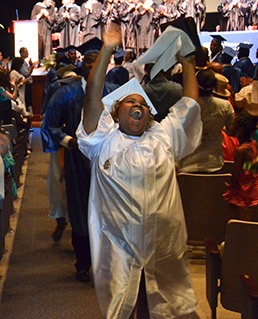

IndyMet graduate Latoya Phillips, winner of the Teresa S. Lubbers Award, leads the recessional after the June 4 graduation at the University of Indianapolis. (IBJ Photo/Gene Herndon)

IndyMet graduate Latoya Phillips, winner of the Teresa S. Lubbers Award, leads the recessional after the June 4 graduation at the University of Indianapolis. (IBJ Photo/Gene Herndon)And the charter school takes the results seriously. This past year, Indy Met overhauled its educational program in large part because a big chunk of its graduates were dropping out of college before finishing a degree—and feedback indicated the school had not done enough team projects to prepare them for a college curriculum.

“The ultimate indicator of how well we do is how our kids do in the next phase,” said Jim McClelland, CEO of Goodwill Industries of Central Indiana, the not-for-profit group that created Indy Met.

Many state leaders would like the same to be true for all public high schools in Indiana. They are trying to create systems that feed information on each student’s success (or lack thereof) in college and even in a career back to the high schools they attended.

The stakes for such an effort are huge. Indiana ranks No. 43 in the nation in the percentage of its population with a bachelor’s degree—at a time postsecondary education has become the ticket to a middle-class income. Yet among all high school freshmen in Indiana, fewer than one in four goes on to earn a college degree.

If school leaders can see how many and which of their students struggle in college or need remedial work, they might be able to change their approaches to better prepare students for what comes next.

That’s exactly what Indy Met has been doing since late last year after realizing its existing approach was failing far too many students.

School leaders had prided themselves on graduating 76 percent of their students within six years and getting nearly all of them accepted to college. On top of that, 69 percent of its college-bound graduates either completed a degree or were still working on it two years later.

That’s a strong persistence rate, considering that only 70 percent of college freshmen statewide—at both four-year and two-year schools—even return for a second year, according to the most recent data from the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems.

It’s even more impressive considering that Indy Met, like most inner-city schools, has high percentages of students who are poor, who are minorities and who require special education—all groups that, on the whole, struggle at the college level.

It’s even more impressive considering that Indy Met, like most inner-city schools, has high percentages of students who are poor, who are minorities and who require special education—all groups that, on the whole, struggle at the college level.

But Indy Met realized that nearly all its alumni who did not remain in college at least two years were those who had graduated with waivers from the state after failing to pass required state standardized tests, a common practice in Indiana.

“If our mission is to graduate kids, then we’re good. Mission accomplished,” said Indy Met Superintendent Scott Bess. “If your mission is to prepare kids for what comes next, then I felt there was a moral imperative to do something about it.”

So he and other Indy Met leaders made a series of changes designed to increase the school’s academic rigor—and in the process get more students to pass the tests required for graduation, now called End of Course Assessments.

That’s exactly how high schools should use data from colleges to improve their performance, said Vic Borden, a professor of education leadership and policy studies at Indiana University.

The trouble is, high school administrators face myriad other state requirements they have to contend with first—obligations that only increased after the Legislature passed landmark school reforms this year.

“It’s very hard for K-12 systems to use these things, because their attention is so spread,” Borden said. “Now the Legislature has raised whole new things. … The demands are so intense; they’re from all over.”

Taking stock

Borden has contributed to multiple projects over the past two decades aimed at feeding performance data from colleges to high schools or to employers as a basis for improving educational performance.

One that is ongoing: annual high school feedback reports prepared by the Independent Colleges of Indiana, an association of the state’s private colleges. Since 1996, it has compiled students’ grades in specific freshman-year courses from all public and private colleges in Indiana.

High school administrators can download the reports for their students from the Independent Colleges website. The reports show the number of students from a particular school who attended each college, and how many earned A’s, B’s, C’s, D’s or F’s in common first-year English, math, social science, science and remedial courses.

The results for each school’s students are then compared with the total performance of each college’s freshman class that year.

Mary Ellen Hamer, director of strategic communications for Independent Colleges, said the reports are in high demand among superintendents and principals across the state, who often use them during faculty retreats or fall planning meetings.

Steve Baker, principal at Bluffton High School near Fort Wayne, said he presents the results of the Independent Colleges report each year to his local school board. Also, some Bluffton teachers have used the reports to see what skills were lacking in Bluffton’s graduates.

“I use them religiously. Religiously,” Baker said, adding, “I need to know how my students are doing at the next level.”

In 2010, the state Commission for Higher Education began publishing high school feedback reports, telling schools which of their graduates had to take remedial classes when they reached college.

The commission and Independent Colleges are working to send their reports at the same time this year and, over the next few years, meld them into one.

But the really valuable information will come when high schools are able to do the kind of sorting of data Indy Met did, so particular patterns in high school are identified as leading to either good or poor outcomes in college.

For example, Ivy Tech Community College President Tom Snyder has argued frequently that if high schoolers don’t take math courses their senior year, they are inevitably too rusty to take on college math the following year.

Going even further, educators could use another data-tracking system to identify patterns at both the high school and college levels that correspond with success (or failure) in the work force.

In development since 2006, the Indiana Workforce Intelligence System so far can track graduates from each of Indiana’s state universities to see what degree they earned, what job they landed, and what salaries they earn.

The state Department of Workforce Development uses the system to identify careers and degrees that are in high demand. But even after five years and $3 million in grant money, it’s difficult for outsiders to get information from the system.

The state Department of Workforce Development uses the system to identify careers and degrees that are in high demand. But even after five years and $3 million in grant money, it’s difficult for outsiders to get information from the system.

The Indiana Department of Education recently linked up K-12 data to the work-force and higher-ed information in the Workforce Intelligence System. But analysis of the data has yet to begin and the department could not say when such data might be available to high school administrators.

More feedback, less remediation?

Teresa Lubbers, Indiana’s commissioner for higher education, said she hopes greater feedback for high schools will help reduce the need for remedial classes in college. Research shows that three-fifths of students who need remedial classes never are awarded a degree.

Still, she acknowledged that the state might need to come up with an incentive to encourage high schools to put the tracking data to use.

For Indy Met, it was only when the school was preparing its case to win a renewal of its charter from Indianapolis Mayor Greg Ballard that it discovered the connection between students graduating with waivers and those failing to finish college.

But most schools never go through such a process—where the failure to win renewal means the school gets shut down.

It will be years before Indy Met knows whether the changes it made this year will move the needle for its graduates. And even with good information about students and post-graduation support, it’s hard for a high school to have any control over whether they complete a degree or not.

Jason Sutt, a 2008 Indy Met graduate who went to Vincennes University, said he often called his former Indy Met teachers to help him on college math problems or to proofread one of his English papers.

“Even after graduating from the Met, you still have that personal bond with teachers outside of school,” Sutt said.

Still, despite the tracking and support, Sutt didn’t finish at Vincennes. He didn’t like the special ed teaching program he was in and struggled with some of the social pressures of college. He left after a year-and-a-half.

He intends to enroll this fall at Ivy Tech to become a nurse practitioner.•

— IBJ reporter Francesca Jarosz contributed to this story.

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.