Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA new law that will expand the number of charter schools in Indiana also could increase the number of teachers at those schools without licenses.

It’s a concept that has become popular in some education-reform circles as a way to provide easier entry into teaching for people from other careers. But it remains controversial, as some with traditional education training challenge whether such teachers can be effective.

Kelly Geisleman, a student teacher and senior education major at Butler University, helps freshman DaMontae King in political science class at Shortridge Magnet. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)

Kelly Geisleman, a student teacher and senior education major at Butler University, helps freshman DaMontae King in political science class at Shortridge Magnet. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)Under the law, 10 percent of teachers can be unlicensed at any charter school in the state. Charters that want to go beyond that 10 percent can ask the state for a waiver to increase their percentage.

At a charter such as Indianapolis Metropolitan High School, where about half the staff comes to teaching through non-traditional routes, that opens the door for more professionals such as engineers, physicians and politicians to teach—and increases the teaching pipeline in much-needed fields such as math and science.

It also adds experts, who proponents say bring a fresh perspective.

“Here’s someone who has done it, who has lived it,” said Indy Met Superintendent Scott Bess, who returned to education after leaving a job teaching middle school math to work in IT for several years. “They have the aptitude.”

His last point remains a topic of debate.

Opponents question how effective teachers with subject-matter expertise but little classroom experience are at conveying complicated information to students. That’s particularly true, they say, when it comes to reaching the challenging student populations many urban charters serve.

“Teaching at a middle school or high school level isn’t about being an expert in content. It’s about teaching kids to learn,” said Alene Smith, a 22-year educator who teaches social studies at Indianapolis Public Schools’ Shortridge Magnet High School. “Some students are in foster care; others have emotional problems. … They don’t care if you have a PhD.”

But as the state opens the door for more flexibility, it’s likely that some schools will trade pedagogy for professionals.

What’s still unclear is how that will play out in classrooms.

Some studies show that certification status has at most a small impact on student test performance. And there are schools where largely unlicensed teaching staffs have produced outstanding results.

Looking west for inspiration

Before the new law, which takes effect July 1, all teachers had to be licensed by the state.

That doesn’t mean they all had a four-year education degree and classroom experience. Those transitioning into the profession can get a so-called emergency license to teach for three years before they’re fully licensed.

In those cases, the teachers are taking education courses while they’re teaching, and they eventually obtain their certification.

The new law allows charter schoolteachers who enter from a different profession to avoid certification altogether. It would be up to schools to provide mentorship and training to help teachers learn to handle the classroom.

Other states already provide that leeway on a broader scale. Arizona, for example, doesn’t require any teachers at its 511 charter schools to be licensed.

As originally written, Indiana’s legislation would have allowed up to 50 percent of teachers at charters to be unlicensed, but lawmakers scaled that back.

State education leaders, though, say providing such flexibility can enable teachers to be trained in ways that makes them most effective.

“I want teachers to be consumers of preparation based on the needs of children,” said Indiana Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Bennett. “That’s going to be a major paradigm shift.”

To prove the approach is effective, Bennett and other education leaders looked to Arizona, where a charter school operator has been hiring mostly unlicensed teachers and producing stellar results.

In fact, Indiana’s push for more license with licensing was driven by the desire to attract the schools, called BASIS, to Indiana.

Just 24 percent of teachers at BASIS’ three schools are licensed. The schools recruit teachers who have strong knowledge in the areas they teach. Before they’re hired, prospective teachers must give a couple of mock lessons to show their aptitude to convey what they know.

Once they’re on staff, BASIS teachers go through a week-long summer program to learn basic teaching methods. They also have access to ongoing training throughout the year.

“We want to hire teachers who are experts, give them as much autonomy as possible, and hold them accountable for results,” said Arwynn Gilroy, the school’s communications director. “It’s much more difficult to learn a subject than it is to convey something you know to students.”

Those who teach education agree subject-area knowledge is important, but learning how to communicate it to students is equally critical.

“Having content knowledge alone is not sufficient to be an effective teacher,” said Lindan Hill, dean of the School of Education at Marian University. “You’ve got to be a manager of group psychology. A teacher has to convince 20 to 40 students every day they want to be in that classroom.”

Teacher perspectives

New teachers from both traditional and alternative backgrounds say they’ve learned how to do that mostly through classroom experience.

Eric Nentrup began teaching at Indy Met in August 2009 after seven months of courses in a transition-to-teaching program at Indiana Wesleyan University.

Nentrup, who entered the field after running his own video production company and working in marketing, is still taking those classes. But he said what prepared him most for his own classroom was a semester-long stint teaching computer graphics through a vocational program at Columbus North High School in 2004.

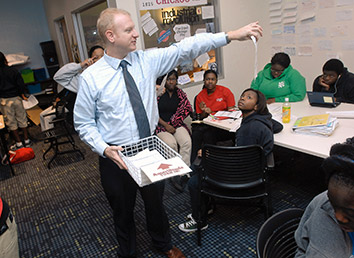

Teacher Eric Nentrup makes sure his students have turned in their homework. He became a teacher after working in marketing and video production. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)

Teacher Eric Nentrup makes sure his students have turned in their homework. He became a teacher after working in marketing and video production. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)It was there that he discovered so-called project-based learning, which minimizes lecture time and lets students collaborate to solve problems—an approach he employs frequently in his junior American history/literature class at Indy Met.

For a recent project, Nentrup divided students into groups to research a city’s growth during the Industrial Revolution. He assigned student leaders—whom he called “mayors” of those cities—to guide the groups.

“I am pushing against the notion that students come in on autopilot,” said Nentrup, who views his classroom as a creative agency in which his students are employed with carrying out projects. “It’s a … shift to come into the classroom and have your teacher teach you like a supervisor.”

Nentrup has a casual approach with students, rewarding good work with fist bumps and encouraging them to use laptops and iPads to do research, sometimes at the risk of losing them to YouTube or Twitter. Every day is a lesson in how to effectively employ that philosophy. Sometimes, he has major breakthroughs.

About a month ago, Nentrup got fed up with students’ persistent disruptive behavior in one of his classes. Instead of scolding them, he left the classroom and sat in a chair right outside the door.

Gradually, his students followed, and he told them to pull up a chair if they were interested in learning. Since then, he said, their cooperation has been significantly better.

“It was one of those halcyon clear moments,” Nentrup said. “I realized it wasn’t about classroom management. It was about human leadership.”

What would have been the best preparation for teaching, Nentrup said, is not more academic coursework but time spent as an assistant to a seasoned teacher.

Such classroom learning has been a core component in preparing Kelly Geisleman, a senior education major at Butler University who is completing her last semester of student teaching at Shortridge Magnet.

Geisleman, whose project-based teaching style and friendly interaction with students is similar to Nentrup’s, said her coursework in teaching methods helped her in the classroom. But what was most critical, she said, was time in the seven classrooms where she’s either observed or taught since freshman year.

Even with that experience, Geisleman said, figuring out how to run a classroom is hard, and she has a tough time imagining how difficult it would be if she were thrown in without training.

Smith, the 22-year teacher supervising Geisleman, said learning skills such as how to command students’ respect takes years of experience.

That was obvious one morning during Geisleman’s class when a group of sophomores was working in groups to select juries from lists of hypothetical characters. A pair of students who weren’t engaged in the project sneaked in a card game as Geisleman was busy helping their classmates.

When the pair saw Smith enter the classroom, they hastily put the cards away.

Effectiveness in dispute

Geisleman’s experience could underscore some educators’ arguments about why a licensing process is important.

Gerardo Gonzalez, dean of Indiana University’s School of Education, said allowing teachers in training to spend time in classrooms with mentor teachers is crucial—as is instruction about how to teach a certain subject and to a particular grade level.

“Having teachers who are not certified at all teaching students is a disservice to the students and teachers because you’re putting them in situations that, in many cases, they can’t handle,” Gonzalez said. Licensing “is the mechanism the state has to ensure that every teacher has met the minimum standards necessary to be a practicing teacher.”

Gonzalez points to a national study that IU commissioned to look at the relationship between teacher credentials and student achievement. The results, released last year, showed that fourth- and eighth-grade students whose teachers majored in education scored three to six points higher on standardized English and math tests than students whose teachers majored in something else.

However, a 2006 study that looked at the impact of teacher licensing in New York City public schools using six years of test-performance data showed little difference in the student-achievement impact among certified, uncertified and alternatively certified teachers.

BASIS’ results seem to exemplify that. The schools tout 100 percent pass-rate on state tests, and 87 percent of students pass AP exams.

The school doesn’t track students’ income levels, but officials estimate about 20 percent of students at the BASIS school in Tucson qualify for free and reduced lunch—a much lower percentage than in urban schools such as Indy Met.

Nonetheless, school advocates say BASIS’ results provide a strong argument that licensing shouldn’t be a prerequisite for teachers.

Those at BASIS and educators such as Gonzalez concur that critical teacher learning takes place while they’re instructing.

Where they differ is whether it should be left up to the state—or the schools themselves—to ensure that classroom time translates into quality teachers.

Bess said charters such as Indy Met have a strong incentive to make sure teachers are effective. If they don’t, they’re not only subject to state intervention but also could be shut down by authorizers.

Still, even proponents acknowledge that with looser licensing requirements, the state no longer has a direct way to monitor whether all teachers are qualified for their jobs.

But if there’s added risk, they say it’s worth taking.

“The flexibility to bring in someone who is extraordinary in the content area is a good thing,” Marian’s Hill said. “To say no one can teach without a license misses out on some significant opportunities for some great instruction.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.