Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe built environment that turned a trackless forest along the White River into a thriving metropolitan area nearly two centuries later would not have been possible without the inspired creations of construction, design, engineering and architectural professionals.

The city’s very essence was laid out 195 years ago by surveyors Elias P. Fordham and Alexander Ralston. The two designed a Mile Square Plan that provided for 100 blocks with 12 lots on each block. A central circular block would anchor a grid system for the Mile Square, which would be bisected by four, broad diagonal boulevards. Ralston, a Scotsman who had assisted in mapping the District of Columbia, paid homage to many of the ideas Pierre L’Enfant incorporated in the design layout for Washington, D.C.

By 1850, Indianapolis was a growing community of 8,000 people, with the Bates’ and Little’s hotels and the Odd Fellows Building beginning to define the downtown boundaries along Washington Street. South of downtown, the Union Terminal would be built in 1853 to give form and function to the city’s growing reputation as the rail Crossroads of America.

A city wouldn’t be a city without entertainment, and in the 1850s that meant the Indiana State Fair. The fair began its annual run at Military Park downtown in 1852. In the 1860s, it moved north to a plot bounded by 19th and 22nd streets, and Delaware and New Jersey streets. In 1891, the state fair board purchased the 219-acre Jay Voss farm northeast of the city. Bounded on the south by then-Maple Road, and what most residents have long known as 38th Street, and on the east by Fall Creek Boulevard, the state fairgrounds has been hosting the fair at the site for 122 years.

Indianapolis also prided itself on its green spaces. The city’s extensive system of parks and parkways dates to the early 20th century. During his last term as Indianapolis mayor in 1900-1901, Thomas Taggart established the nucleus of a city park system when he purchased 900 acres along White River.

Long before Indianapolis was ringed and bisected by interstate highways, a system of tree-lined boulevards designed by George E. Kessler carried automobile and carriage traffic from one end of the city to the other. The Indianapolis Board of Park Commissioners hired Kessler as its consultant, and he presented a comprehensive plan for parks and boulevards to the city in 1909. The plan called for a chain of parks every five blocks, linked by a series of wide, shaded boulevards.

Over the next two decades, the city put much of Kessler’s plan into reality, building boulevards along White River, Fall Creek, Pogue’s Run and Pleasant Run Creek. Kessler designed the Meridian Street Bridge over Fall Creek using a postcard of an Italian bridge as his inspiration, and his creation of the Sunken Gardens at Garfield Park was copied by landscape designers around the world. Following his 1923 death, Indianapolis completed the outer boulevard plan the nationally renowned landscape architect was working on and named it in Kessler’s honor.

The city kept expanding parks and public golf courses outward into the suburban reaches of Marion County during the 20th century, and created an innovative series of recreational trails during the 21st century, including the Monon Trail and Pennsylvania Trail along abandoned rail rights of way, and the Cultural Trail downtown.

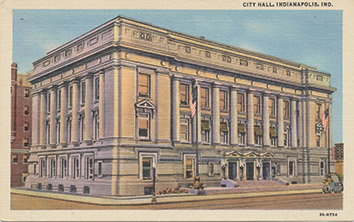

Homegrown architecture firms like Rubush and Hunter also helped the city’s commercial venues to transition from a 19th century to a 20th century city. Preston Rubush and Edgar O. Hunter helped transform downtown in the first third of the new century. Their body of work included the new City Hall at 202 N. Alabama St., the Masonic Temple on North Illinois Street, the Columbia Club on the Circle, The Circle Theatre, the Indiana Theatre and the Hume Mansur Building. Their later work included Circle Tower—the city’s pre-eminent downtown art deco building, on Monument Circle—and the Coca-Cola Bottling Plant on Massachusetts Avenue, which is targeted to be repurposed for 21st century mixed-use development.

A steam-fired, steel-wheel tractor compacted the turns at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in about 1909.

A steam-fired, steel-wheel tractor compacted the turns at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in about 1909.The built environment also included a number of iconic sports facilities. By 1911, the city was already regarded as the top automobile proving ground in the country. Frank H. Wheeler and Carl G. Fisher were making carburetors and headlamps in Indianapolis in the first decade of the century. In 1911, they teamed with James Allison to hold the first Indianapolis 500-mile race at the 2-1/2 mile oval they built on West 16th Street near the village of Speedway. The 500-mile race was suspended during World War II, but Terre Haute entrepreneur Anton Hulman bought IMS in 1945, and he and his heirs transformed it into an international sporting event.

Indianapolis has always been the hub for Hoosier Hysteria, and in 1928, Butler University celebrated its move to the Fairview Park campus on the northwest side by building Butler Fieldhouse, perhaps the nation’s most iconic basketball facility. The fieldhouse, later renamed in honor of Butler Coach Tony Hinkle, long hosted the Indiana High School Athletic Association boys basketball tournament and still is home of the Butler Bulldogs basketball team.

Professional basketball came to Indianapolis in the 1960s with the organization of the American Basketball Association’s Indiana Pacers. After dominating the ABA, the Pacers were one of a handful of teams admitted to the dominant National Basketball Association in 1974.

The administration of Mayor Richard G. Lugar had seen the potential of professional sports to help renew downtown. In 1974, the city opened the 17,000-seat Market Square Arena at Alabama and Market streets as the home of the Indiana Pacers. When the Capital Improvement Board opened an arena to replace Market Square Arena in 1999, the architects of Bankers Life Fieldhouse paid tribute to the heritage of Hinkle Fieldhouse.

Professional football took a much more circuitous path to arrive in the Hoosier capital city. Indianapolis was abuzz with rumors through much of winter 1984 about the city’s negotiations to secure a National Football League franchise. The city was in the final stages of completing the then-Hoosier Dome, a massive domed stadium just south of downtown, that Indianapolis hoped would provide for its entry into the NFL. The $82 million stadium would have proved to be an expensive white elephant had the administration of Mayor Bill Hudnut failed in its quest for an NFL team.

The rumors became reality in March when Robert Irsay, owner of the Baltimore Colts, packed up his team in the middle of the night and moved lock, stock and barrel to Indianapolis. Irsay, who had long feuded with Baltimore and Maryland officials, rubbed salt into the wounds when he selected Mayflower, an Indianapolis-based moving company, to haul his team west. The Indianapolis Colts played in the RCA Dome 23 years before the city replaced it with Lucas Oil Stadium in the same southwest quadrant of the Mile Square.

The built environment in the 21st century is the result of nearly two centuries of cooperation among city planners, architects, designers, engineers and construction firms. That is a collaborative endeavor that will likely guide the city’s direction in a third century of growth.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.