Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWilliam H. Hudnut III, the longest-serving mayor of Indianapolis and a towering figure who led the city out of its post-World War II decay in the final decades of the 20th century, died Sunday at age 84.

Hudnut's death was confirmed by Dave Arland, a former aide. Hudnut had suffered from numerous health problems, including congestive heart failure and complications from throat cancer.

Hudnut, the only mayor of Indianapolis to serve more than two terms, was the city's cheerleader-in-chief during his four terms as mayor from 1976 to 1991. The 6-foot-5 Hudnut visibly embraced the role of leader, whether driving a snowplow during the epic Blizzard of 1978 or donning a leprechaun costume in the city's annual St. Patrick's Day Parade.

"Bill Hudnut was a big man in all the ways that count most. Big heart, big dreams and a wingspan big enough to wrap around any citizen who wanted to help him make Indianapolis a greater place," said Purdue University President Mitch Daniels, who was Hudnut's campaign manager in 1972, when he was elected to Congress.

Hudnut's biggest Indianapolis legacy is the transformation of downtown from a city center struggling to remain relevant into an economic engine built on conventions and sporting events. Downtown's renaissance lifted the Indianapolis region, and some would say the entire state.

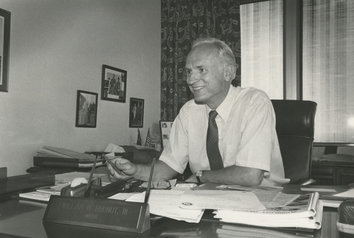

In one of the defining acts of his tenure, Hudnut was able to persuade the owners of the Baltimore Colts to relocate to Indianapolis. The team arrived via Mayflower vans on March 28, 1984. (Image courtesy Institute for Civic Leadership & Mayoral Archives at the University of Indianapolis)

In one of the defining acts of his tenure, Hudnut was able to persuade the owners of the Baltimore Colts to relocate to Indianapolis. The team arrived via Mayflower vans on March 28, 1984. (Image courtesy Institute for Civic Leadership & Mayoral Archives at the University of Indianapolis)"History will judge him for what he did in bringing the community together to tackle the revitalization of downtown," said David Frick, who served as deputy mayor under Hudnut in the late 1970s and remained a key adviser throughout Hudnut's mayoralty.

"He was a consensus builder," said Frick, noting the Republican met frequently with Democrats and organized labor. "Politicians these days tend to retreat to their core supporters. He was always looking for input from different parts of the community."

Shortly after taking office, Hudnut convened leaders from the business and not-for-profit sectors to map out the future of a city battered economically by suburban flight and the waning fortunes of large manufacturers located here. The consensus was a future that relied on sports as a driver of economic development and a tool for bringing life to the city's downtown.

That vision led to two transformative achievements of the Hudnut era: development of Circle Centre mall and the relocation of the Baltimore Colts to Indianapolis.

Taking risks

The $300 million Circle Centre reversed the decades-long flight of retailers from downtown. Its opening in 1995 was the culmination of 17 years of planning that started in Hudnut's first term. Though the mall didn't open until after Hudnut left office, much of the heavy lifting was done by Hudnut and his team working hand-in-hand with Melvin and Herbert Simon, the famous retail developers who partnered with the city on Circle Centre.

"I can't tell you how much time I spent talking to the Simons and other retailers about how we could build a retail presence in the downtown," said Frick, recalling constant setbacks. "Every time we'd get a retailer lined up they'd get bought by another retailer."

Hudnut's biggest gamble as mayor was tied to the city's quest to land a National Football League franchise. "It became pretty clear we were going to have to have a place to play before we could get a team," said Frick, who was in the thick of the effort with Hudnut.

That led to construction of the 60,000-square-foot Hoosier Dome—essentially an expansion of the Indiana Convention Center—which opened in 1984. "It was going to be Hudnut's folly if we didn't get a franchise," Frick said.

When chances of landing an expansion NFL team fizzled, Hudnut pursued the Baltimore Colts, famously working with Colts owner Robert Irsay to orchestrate the team's late-night move to Indianapolis before the Maryland legislature moved to block the team's relocation.

Hudnut was known for a roll-up-your-sleeves management style, whether that meant riding along with snowplows or helping patch streets. (IBJ file photo)

Hudnut was known for a roll-up-your-sleeves management style, whether that meant riding along with snowplows or helping patch streets. (IBJ file photo)Landing the Colts in 1984 followed a broader strategy of using sports—initially amateur sports—to revitalize Indianapolis. Hudnut worked with the Lilly Endowment and the Indiana Sports Corp., a not-for-profit created in his first term, to build the infrastructure to host various national and international sports championships. The Indianapolis Tennis Center (since demolished), the Major Taylor Velodrome, and the Natatorium and the Michael A. Carroll Track & Soccer Stadium at IUPUI are among the venues that helped the city lure the 1982 National Sports Festival and the 1987 Pan American Games.

Hudnut's Indianapolis success story made him a sought-after speaker and leading authority on urban revitalization after he left office. He taught at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and Georgetown University and became a senior fellow at The Urban Land Institute in Washington, D.C., a role in which he regularly convened public officials, architects, developers and other experts to discuss the revitalization of cities.

From pastor to politics

Hudnut was born Oct. 17, 1932, in Cincinnati to Elizabeth Allen Kilborne Hudnut and William H. Hudnut Jr., a Presbyterian minister. After graduating Phi Betta Kappa from Princeton University, Hudnut decided to follow his father into the ministry, graduating with his master's degree in theology from Union Theological Seminary in New York.

He was ordained in 1957 and served churches in Buffalo, New York, and Annapolis, Maryland, before becoming senior pastor of Second Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis in 1964.

In 1972 he dove into politics, running as a Republican and defeating the incumbent Andrew Jacobs Jr. in the race for the U.S. House seat representing Indianapolis. Hudnut served one term, losing to Jacobs in a rematch in 1974.

Hudnut soon turned his attention to the mayor's office, defeating Democrat Robert V. Welch, a local business leader, in a tight race in 1975 for the job vacated by Richard Lugar. Hudnut was never seriously challenged in his three reelection bids, winning all of them with more than 60 percent of the vote. He lost a 1990 bid for Indiana secretary of state to current Indianapolis Mayor Joe Hogsett.

Hudnut took care to reach out to the city's black community. (IBJ file photo)

Hudnut took care to reach out to the city's black community. (IBJ file photo)Hudnut decided not to run for a fifth term in 1991, but he wasn't through with elected office. He was elected to the town council of the Washington, D.C., suburb of Chevy Chase, Maryland, in 2000 and served as its mayor from 2004 to 2006.

Though he had relocated to the East Coast, Hudnut remained involved and deeply interested in the fortunes of the city he led for 16 years, regularly consulting with Democrat Bart Peterson, who was mayor from 2000 to 2008 and Republican Greg Ballard, who served from 2008 to 2016.

Peterson said Hudnut served as a sounding board and private cheerleader throughout his two terms. And the former mayor gave Peterson some advice that stuck. "This is a city that needs someone to put their arms around it," Peterson recalls Hudnut telling him. "The job is about far more than administering the government and doing development deals. It's about a relationship between the top elected official and the people of the city and keeping that relationship at the forefront of your mind at all times."

Hudnut's legacy, said Peterson, is more than the bricks and mortar that helped resurrect downtown. "He bolstered our self-confidence," Peterson said. "He helped convince us that we could do anything and that we were as good or better than anyone else. That was significant for a city that is famous for not having enough attitude."

Hudnut also became a confidante of Peterson's successor, Greg Ballard, who in 2013 renamed Capitol Commons, the park just north of the Indiana Convention Center, Hudnut Commons. The park includes "Mayor Bill," a slightly larger-than-life-size bronze likeness of Hudnut sitting on a park bench. The sculpture was dedicated in December 2014.

In a statement Sunday, Mayor Hogsett said: "Today, our city mourns the loss of a visionary leader who cared so deeply for Indianapolis that he dedicated much of his career to its transformation. Mayor Hudnut was ahead of his time, helping to turn, as he often said, 'India-no-place' into 'India-show-place' and paving the way for the world-class city that Indianapolis has become."

Stephen Goldsmith, who succeeded Hudnut as mayor, said in a statement Sunday that Hudnut's "vision and energy … truly transformed our city. Perhaps the most valuable part of his legacy was his life-long commitment to inclusivity and tolerance, which he continued to champion long after his elected life ended."

Writing for IBJ in November 2015 about his time in office, Hudnut focused on the qualities of a good leader: integrity, collaboration, respect for others, and joy. "Good leaders, beyond their trials and tribulations, enjoy what they are doing and communicate that enjoyment to others. … I am not saying I possessed all these characteristics when I was mayor of Indy. All I can say is that I tried, and did my best."

On his final post on the CaringBridge.org website, Hudnut wrote: "One cannot choose how one finishes the race, only how one runs it. I would not have chosen a long, slow slide into complete heart failure, but I tried to cope with it with 'gaiety, courage and a quiet mind,' to borrow from my mother who in turn was quoting Robert Louis Stevenson."

He added: "About the journey, it’s been a wonderful trip. As I have said many times, I hope my epitaph will read: 'He built well and he cared about people.'"

Hudnut is survived by his wife, Beverly, and four children. He was preceded in death by two sons, Michael and George, and a daughter, Laura.

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.