Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now The title elements aren’t quite given equal weight in “Sensual/Sexual/Social: The Photography of George Platt Lynes,” the exhibition running through Feb. 24 at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields.

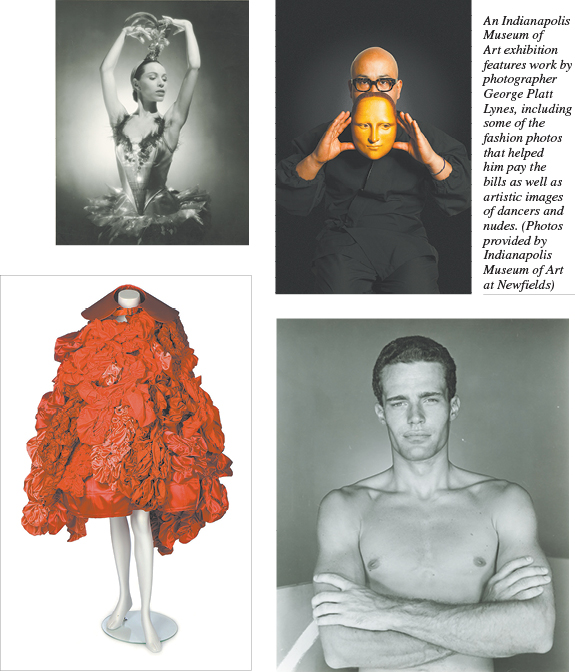

The title elements aren’t quite given equal weight in “Sensual/Sexual/Social: The Photography of George Platt Lynes,” the exhibition running through Feb. 24 at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields.

As for the social, rare is the image that has more than a single subject. And while sexuality is sometimes implied—and male nudity explicit—in the show, the emphasis is on the sensual, with the models formal and artfully lit and accented rather than presented overtly sexually when captured by Lynes.

Visitors to the exhibition—included with museum admission—are given a historical timeline right up front. From there, the exhibition offers a mild introduction to Lynes’ style through galleries of more modest, fashion-focused fare.

His work with publishing legend Diana Vreeland at Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue and shots for designer Henri Bendel remain fascinating three quarters of a century later. (Blame or credit the influence of the surrealists for some of the odder imagery, including a basket of birds on a model’s head.)

Primarily self-taught, Lynes initially shot family and friends, landing his work in gallery exhibitions in 1932 and opening his own studio in New York a year later. He built a relationship with the American Ballet (later New York City Ballet), leading to 20 years of dancers captured dramatically on film, some in motion, some not. Vera Zorina tying a slipper and Tamara Toumanova surrounded by butterflies are standouts. In the 1940s, Lynes reached another level of notoriety, moving to Los Angeles to head up Vogue magazine’s West Coast studio. (He is reported to have destroyed much of the fashion photography that had brought him acclaim while also paying his bills.)

The formality of the dancers and the structure of ballet clearly had an influence, and it shows in Lynes portraits of an array of figures more notable for their work at the typewriter, including Tennessee Williams (shot after “The Glass Menagerie” but before “A Streetcar Named Desire”), Aldous Huxley , e.e. cummings and Dorothy Parker. There’s a charming shot of George Balanchine with a gaggle of young dancers. And Igor Stravinsky and Marc Chagall are also in the cultural mix captured through Lynes’ lens.

Note that all of the above are clothed—although a then-unknown Yul Brynner is included in the nude gallery.

Back in New York in 1948, most of Lynes’ creative energy shifted to dance shots and male nudes. “More than anything,” Lynes said, “beauty is what makes things interesting.” Experiencing his work in such quantity offers a reminder of the inherent imbalance in art history: Heterosexual males gazing at female subjects has been—and remains—dominant.

Here, there’s almost a mythological confidence from and about the subjects. Shot in black and white, often with dramatic shadows and confrontational stares, the usually anonymous subjects seem to demand the viewer’s account for them.

A bit of a local angle comes into play through one of Lynes’ key supporters—Indiana University sex researcher Alfred Kinsey. At a time when simply sending Lynes’ photographs through the U.S. Postal Service was a federal crime, their communication had to be kept secret. When Lynes died in 1955 at age 48, many of his nudes were gifted to the Kinsey Institute.

A revisit to the opening timeline reminds that Lyons faced bankruptcy before his death, with the bank taking his equipment and studio—a sad end for a remarkable and influential artist.

The work of those in his wake provide a key through-line for the exhibition, with shots by Robert Mapplethorpe, Herb Ritts and others sprinkled in under a recurring “legacy” label.

“Sensual/Sexual/Social” is a bold offering for the IMA, more identified lately by brightly colored, whimsical creatures; blooming flowers; and holiday lights than by provocative material that might raise a few conservative eyebrows.

Not that nudity is unheard of at the IMA. It’s male frontal nudity—uninhibited and unapologetic—that makes it distinct.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.