Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhen refugees from Myanmar (formerly Burma), arrive in Indianapolis, they soon learn that one employment hot spot is a collection of Indy-area Amazon distribution centers.

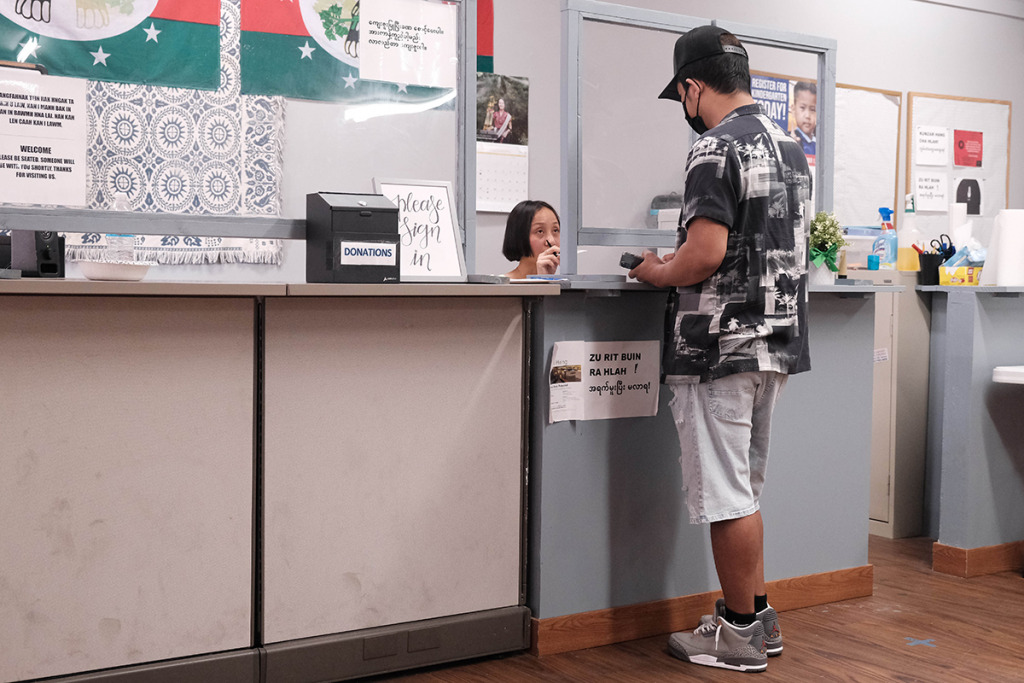

The Chin Community of Indiana, a not-for-profit center run by and for the Chin ethnic minority, has worked for years to develop a relationship with the company. Known as the Chin Center, it has helped at least 7,000 refugees and other immigrants land jobs there and at other businesses.

“A lot of companies and other staffing agencies are asking to do a job fair here,” said Dally Ta, an employment specialist at the Chin Center. “We already have a book of people that want to partner with us.”

Walmart and FedEx are other popular workplace destinations for Indianapolis immigrants, since the companies also have local distribution centers. Workers from the same country can end up clustering in the same warehouses, working side by side.

Organizations like the Chin Center partner with employers to make clusters on purpose, filling empty positions, getting refugees jobs and making it easier to manage the language and transportation barriers that arise.

The practice helps explain why so many Sikhs work for the FedEx Ground facility near Indianapolis International Airport, a concentration that became a matter of heightened curiosity last month after eight employees were killed when a former worker opened fire and then killed himself. Half of the victims were Sikh, members of the world’s fifth-largest religion, which originated in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent.

FedEx said it could not answer questions about what percentage of the facility’s workforce is Sikh because it does not collect information on its employees’ religious affiliation. The company said in a statement that it was “proud of our inclusive and diverse workforce,” and that it stood “in solidarity with all of our team members during this difficult time, including those of the Sikh community.”

One thing is clear: Such workplace clusters are common.

On average, 37% of immigrants working in urban America had co-workers who were also immigrants, according to a 2014 study published in population research journal Demography. Only 14% of a native-born employees’ co-workers were immigrants.

‘A Match.com’

Sometimes, the workplace clusters happen on their own. Immigrants often find jobs by word of mouth through networks that include other non-native family members, friends and community organizations like places of worship or cultural centers.

“The employer might find people from a specific group … and those workers will expand that information to their networks,” said Mónica García-Pérez, an economics professor at St. Cloud State University who researches immigrant labor, and a co-author on the 2014 study.

“Having employees from a particular group will continue to increase the chances that the new hires are going to be [from] similar countries,” García-Pérez added.

If someone’s friend or family member needed a job, other members of the community would encourage them to join places like FedEx, said K.P. Singh, a well-known Sikh community leader, activist and artist. The facility had become something of a gathering place for the community.

“The workforce was something they could easily relate to … with a language commonality, a cultural commonality,” Singh said. Sikhs “were gravitating toward that place because they felt it was friendly, with lots of people from their own community.”

Other times, employers, resettlement organizations, staffing agencies and prospective employees collaborate to purposefully create clusters. Employers can fill multiple positions in one go, while resettlement agencies can help several clients at a time and groups of immigrants can get hired.

The network “reduces the cost on both sides, on employees and workers, of finding that match,” García-Pérez said. “It’s like a marriage. Having a ‘Match.com’ increases information flow.”

Like with any other candidate referral, she added, employers can be more confident in their hiring if they’re happy with relatives and friends already on staff.

But workplace clusters are also a way to overcome language barriers for employees with a limited knowledge of English.

“We started to place some of our clients who are fluent in English … in a leadership position, like a supervisor or trainer,” said Sajjad Jawad, employment services supervisor at Catholic Charities Indianapolis’ refugee resettlement arm. “That supervisor or trainer will be in charge of all people coming from his own community.”

That way, “you can have some people that don’t speak English working on a team,” said Cole Varga, executive director of Exodus Refugee Immigration, another major resettlement agency in the city. Exodus also uses the strategy, which Varga called a “pod system.”

When employees can communicate easily, it cuts down on the time and effort it takes to coordinate work, according to García-Pérez.

The clusters also make it easier for resettlement agencies to set up carpools for their clients, who typically can’t get a driver’s license or buy a car right away.

“In Indianapolis, we don’t have the best bus system, so we make a carpool plan with other clients and they can go [to work] together,” Jawad said.

Carpooling is also a good way to pair recent arrivals with more established refugees who drive, own cars and can help newcomers settle in and learn the lay of the land, according to Varga.

On-premise opportunities

Starting any new job can be intimidating, but even more so in a new country with a different dominant language.

It can be hard for people who do long shifts to get to language classes, so offering them on-site sessions, right at work, can help. But that’s easier said than done, according to Varga.

It can be hard for people who do long shifts to get to language classes, so offering them on-site sessions, right at work, can help. But that’s easier said than done, according to Varga.

“We’ve talked about doing more English instruction with employers over time. It just gets hard,” he said. “Employees can’t lose the hour of work time, and it’s unfair to make them do it over their lunch. So you need employment partners that are willing to pay for it, basically.”

So the organization has been focusing on its own offerings, Varga said, doubling attendance during the pandemic thanks to the convenience of virtual classes.

Catholic Charities and the Chin Center, like other local refugee and immigrant organizations, also offer English instruction.

Morales Group, an Indianapolis-based and immigrant-run staffing agency, tries to match the diversity and languages represented in prospective employees with its staffing agents, said CEO and President Seth Morales.

“We want our employees that come through, to go to work, that they feel like somebody can speak their language or understand a cultural difference,” Morales said.

Workers come from all over, whether they hear about Morales Group by word of mouth or are connected through partnerships with organizations like Catholic Charities, Exodus and the Chin Center. The company has multiple employees who help move resettled applicants through the hiring process more quickly, Morales said.

About 250 to 300 people work at the company’s warehouse, he said, in addition to those in the corporate and staffing office and the thousands who hold jobs at other distribution centers or manufacturers through the Morales Group.

The company holds cultural-diversity training sessions for its own employees and for other organizations, Morales said, along with monthly town halls with major players like resettlement agencies and community organizations.

“We all talk about what’s working right now in the community and what’s not,” he said. “… It’s a good way to create dialogue, like, ‘Hey, we’ve got some challenges right now [with] transportation,’ or, ‘There’s a certain set of employers that aren’t willing to do this,’ and we need to find different ways to help.”

‘Self-fulfilling’ clusters

Fully 64% of the 4,637 refugees Indiana has admitted since fiscal year 2016 were from Myanmar, according to data from the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. In total, nearly 24,000 people originally from Myanmar lived in Indianapolis in 2020, according to the Burmese American Community Institute—mostly in Perry Township, Southport and Greenwood.

Ngung Tling arrived in Indiana as a refugee in 2015 and found a job driving forklifts at auto-parts manufacturer TOA USA in Mooresville. It took him just a few weeks to adjust, Tling said, having already driven forklifts during his six years in Malaysia.

But it helped, too, that Tling’s employer sent translated weather notifications via text and had notices on its website available in Chin, he said.

But other everyday documents, like utility bills, are a different story, despite the Chin Burmese community’s growing numbers. Tax season, for instance, always brings an influx of people asking for help, said Lian, the Chin Center manager.

Helping community members land jobs typically means working through an English-language application form, even for work that doesn’t require much English knowledge.

“Even just one paper, they will bring it to see what it is about, even if it’s just [an] advertisement,” said Ta at the Chin Center.

And the help isn’t just on paper. Ta described intermediating between community members and companies like AT&T, on phone calls lasting up to three hours. People even call the center for help after accidents, Lian said.

The Chin conentration here can help draw more Chin people from all over the country, center administrators said.

“A lot of them hear about Indianapolis being a great place to live, low cost of living, you can get jobs here,” said Jeff Lake, a center board member who volunteers in-person daily. “And you can also get support, because they have this Chin Center, which, that’s very rare.”

As the community continues to establish itself, more Chin people are moving up in the workplace. Amazon, Lake said, has expressed interest in supporting Chin employees’ gradual transitions to leadership positions.

Center administrators even met a Chin team leader while at a facility in mid-April, he added, who likely helped new Chin hires get settled.

“That’s why they want more people like her,” Lake said.

Long-term sustainability

And that’s ultimately the goal for employment services, whether from local organizations or refugee resettlement agencies: long-term sustainability for immigrant communities.

“We’ve seen that happen a couple times,” Varga, from Exodus, said. “We’d develop an employment partner and then eventually, they promote someone up to an HR position, and then the company doesn’t even need us because it’s just self-fulfilling.”

That’s the path successive immigrant communities have taken in Indianapolis across the centuries, said Singh, the Sikh community leader. British colonists moved to this area when it was still officially native land, followed by the Irish, Germans, enslaved and later free Black Americans, Eastern and Southern Europeans, and South Asians and Hispanics, according to the Indiana Historical Society.

Singh arrived in Indianapolis in 1967 as one of a handful of Punjabi Sikhs. On his first day of work, an Indy newspaper put him in a column on local oddities. A restaurant wouldn’t serve him unless he took off his “hat”—the turban that is an integral piece of Sikhism.

Decades later, the community is well-established and numbers in the thousands, with eight houses of worship serving the area. But its members continue to face discrimination and violence.

Still, Singh said, “We’ve come a million miles,” noting how Gov. Eric Holcomb was among those mourning at a memorial service following the mass shooting at FedEx.

Rather than “threaten someone’s dignity,” he said, “… count me in for the gifts I bring. Count me in for the work I do.”

To that end, Varga said he always tells employers: “Refugees are a really great source to find workers from these communities. They’re highly motivated … wanting to contribute. They’re becoming new members of this community.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.