Subscriber Benefit

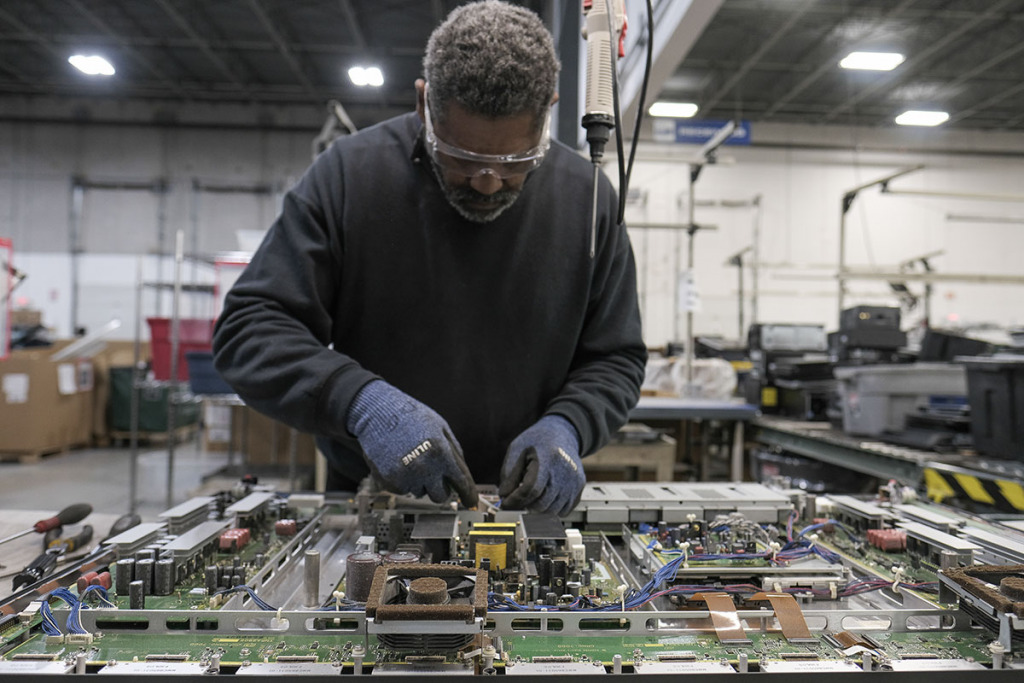

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWith a slight grunt, Darrell Gaines lifted a 52-inch, flat-panel television screen onto his workbench and got busy.

He removed the back of the screen and began unfastening parts inside, tossing metal scraps into one bin, plastic into another and electronic parts into a third. He had to move carefully so he didn’t brush up against toxic chemicals, break a mercury lamp or cut himself on sharp edges.

Breaking down a large screen into parts by hand can take up to 20 minutes and always carries the risk of worker injury.

“You don’t rush it,” said Gaines, a soft-spoken worker at Cascade Asset Management, an electronics recycling firm located on the southwest side.

But soon, Cascade could speed up the process significantly, with the goal of recycling an additional 1,000 tons of electronic material a year.

Last month, the company won a $730,000 state grant that will allow it to purchase automated equipment that can tear down a screen in two minutes or less, much faster than workers can do it by hand. That would give Cascade the capacity to dramatically increase the number of TV and computer screens it can recycle from banks, office buildings and other customers.

“We’ve got plenty of stock to stay busy,” said James Ellison, Cascade’s general manager. “But we’re estimating with the new equipment, we’ll be able to increase capacity between eight- and ten-fold.”

Cascade was one of three organizations in Marion County to win state grants from a pilot program designed to divert millions of tons of waste in Marion County from landfills.

Recycling advocates hope the program will begin to do something about Indianapolis’ bottom-tier ranking for recycling and landfill diversion. But some criticize it for not doing more to help ease Indianapolis toward losing its distinction as the largest city in the nation without universal curbside recycling.

In 2020, the city diverted only about 15% of all residential, commercial, industrial and construction waste from landfills, through a combination of recycling and composting. That was lower than the statewide rate of about 20% and far below the U.S. rate of around 35%.

Recycling advocates say the city and state need to do better.

“When we talk about diversion, we are talking about a resource management issue,” said Pam Francis, president of Circular Indiana, a not-for-profit formerly known as the Indiana Recycling Coalition. “Our resources are finite and becoming increasingly harder and more expensive to get.”

The grant program

The new pilot project could be one way to move forward, but it has attracted some criticism for handing out all of its grants to businesses, rather than helping set up programs to increase curbside recycling.

In addition to Cascade Asset Management, two other businesses landed grants through the pilot program. They are waste giant Republic Services, which got $2 million to install optical sorters to recover black plastics from recycling streams at the company’s Indianapolis recycling center, and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, which got $270,000 to expand public access to recycling through additional receptacles and education.

IMS officials did not respond to IBJ to discuss its plans. A spokesman for Republic Services said its plans were in early stages. He declined IBJ’s request to interview Republic management in Indianapolis.

“Republic Services is making investments to enable greater plastics circularity and improve capture rates,” spokesman Jeremy Walters wrote in an email. “At this time, we are in our initial planning phase and would encourage you to check back with us this summer.”

The pilot project was set up last year through a new state law that set aside $4 million to programs that could increase recycling landfill diversion in Marion County.

Some say the intent of the legislation was to help the county improve its laggard position in recycling, which has been among the lowest in the nation for cities its size.

About a dozen organizations applied for the funds, including the city of Indianapolis, which saw the pilot program as an opportunity to finally get some traction.

The city proposed setting up a partnership with RecycleForce, a not-for-profit recycling operation that helps ex-offenders transition back into the workforce. The plan was to use funding to expand drop-off recycling services by accepting more categories of recycling material for processing at RecycleForce’s new headquarters in Sherman Park on the east side.

Marion County currently has three trash haulers: the city’s Department of Public Works and two large companies, Republic Services and Waste Management. Waste is taken to an incinerator on South Harding Street operated by New Jersey-based Covanta or to the South Side Landfill on Kentucky Avenue.

Mayor Joe Hogsett’s administration has said it wants to establish universal curbside recycling by 2025, the year the city is due to renegotiate contracts with two hauling contractors, the incinerator service and the landfill.

Mixed reviews

Some officials say the Indiana Recycling Market Development Board, which awarded the pilot project grants, should have set aside some funds to help the city start to shift to universal curbside recycling, rather than awarding the money to three companies that will use it for private recycling programs.

“I thought there would be more coordination with the city, and a real focus on more access to recycling for Indianapolis residents,” said state Rep. Carey Hamilton, D-Indianapolis, co-author of House Bill 1226, which set up the pilot program. “I believe we have work to do, because I don’t believe the intention of the law was realized with the expenditure of that first round of money.”

The bill’s primary author, state Rep. Michael Speedy, R-Indianapolis, acknowledged that the funds didn’t go to any programs that would increase curbside recycling. A follow-up bill this year, House Bill 1512, would expand the program for another two years and broaden it out to counties bordering Indianapolis.

That bill is now advancing through the Legislature, but like the original bill, doesn’t specify that the money be used to increase curbside recycling. Speedy said he is trying to correct that with an amendment.

In the meantime, he said he was happy that the companies that won the grants are using them to divert waste from landfills in other ways, such as recycling electronics and black plastics. “We’re headed in the right direction,” he said. “I still think there’s a lot to be done out there. And curbside is a crucial part of that.”

Some environmental advocates applaud the pilot program for its goal of reducing industrial and commercial waste, even if it doesn’t do anything immediately about increasing curbside recycling.

Tim Maloney, senior policy director of the Hoosier Environmental Council, said the efforts being rolled out by Cascade, Republic and IMS “are all positive projects.”

“The notion of helping with the industrial waste stream was certainly a big part of the push for the bill,” he said.

But Francis, the president of Circular Indiana, said corporations “as large and influential” as Republic, Cascade and IMS could have self-funded their projects.

“We were hoping this money would be awarded more in line with expanding resource recovery infrastructure and participation for our residents and communities,” she said.

Republic is a unit of Phoenix-based Republic Services Inc., one of the nation’s largest haulers and recyclers, with operations in 47 states. It had revenue last year of $13.5 billion.

IMS is owned by Penske Entertainment Group, a private company based in Bloomfield Township, Michigan. Cascade Asset Management is a private company based in Madison, Wisconsin.

Francis also expressed concern that the Recycling Market Development Board awarded only about $3 million of the $4 million available through the project when there were other applicants to be considered.

Marion County has one of the lowest recycling rates in the state because of the low fees charged for trash pickup. The current rate of $32 a year was established in 1987 and does not cover the city’s costs, which are estimated at $44 a household.

About 11% of Indianapolis residents subscribe to a private recycling service. The city projects universal curbside recycling could cost $10.4 million to $17.9 million per year or about $3.17 to $5.48 per household per month.

Thrive Indianapolis, the city’s sustainability plan, was adopted in 2019. One of its goals is to provide universal curbside recycling to all Indianapolis households by 2025.

Back on the recycling floor at Cascade Asset Management, workers were busily disassembling all types of electronics, from laptops to an antique 3D printer as large as a coffee table.

Last year, the company disassembled and recycled more than 1.2 million phones, computers and other electronic items. Flat-panel television screen made up about one-third of its intake.

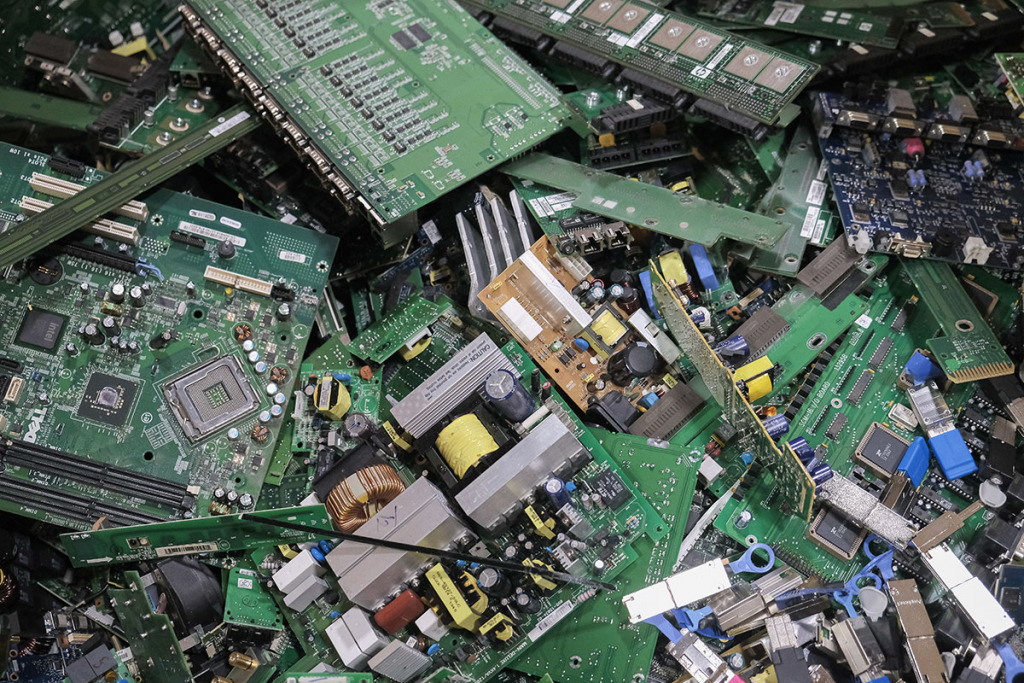

Throughout the large warehouse, huge cartons of sorted materials sat in neat rows, waiting to be loaded into trucks and hauled to smelters, scrap dealers and other companies that will find them a home in new products.

“We just sent a 53-foot trailer of commodities out last Thursday,” said Ellison, Cascade’s general manager, pointing to the shipping area. “Otherwise, there would have been a double stack of containers all the way to the door.”

He said the computers and TV screens come in ebbs and flows. In some peak periods, “there isn’t an extra foot in the building,” he said. “And we just dig our way out, try to stay organized and work through the process. Luckily, nothing in here expires.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.

Who would have thought that heavily Democratic Marion County would have low recycling rates? LMAO

Yeah… An individual house hold has to pay out of pocket to even get a recycling bin and on top of that Republic doesn’t even accept things like plastic bags.

It takes a little practice, but I think our household is recycling at rate of about 2 parts landfill to 1 parts recycling, so maybe 30%. 5% is dismal but understandable.

The graphic is a bit misleading. The tonnage “sent to the landfill” is actually a combined number of tonnage sent to the landfill & to the Covanta Incinerator. Meaning the tonnage sent to the landfill is much less than reported here.

One of the most successful options for recycling newspapers has been halted. The green and yellow Abitibi dumpsters located at schools and other public locations have disappeared! Rumor was that the company/resources were bought out by either WMI or Republic. Sure hope another option develops!