Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThere are many roads to Broadway. “The Phantom of the Opera” was shipped from London. “Les Miserables” was birthed as a French concept album. “Wicked” was developed in workshops before getting a test run in San Francisco.

But if the team behind “The Circus in Winter” has its way (and if enough money can be raised and script kinks worked out), the Ball State University-incubated musical might be the first Tony award winner conceived as a collaborative class project.

The prospect might not have seemed possible when students started working on it in 2010. But the Broadway target is a little closer thanks to the first professional production for “Circus”—courtesy of Goodspeed Musicals, a Connecticut company that has launched 19 shows to Broadway, including “Annie” and “Man of La Mancha.”

Any theatrical production is a risky investment. But “Circus”—a musical drama about the relationships among circus characters in a fictionalized version of Peru, Indiana—has gathered a group of producers and other believers who are putting time and money on the line.

If they are successful, Ball State stands to benefit—both financially and in the national reputation of its theater department.

Immersive learning

The musical “Circus” began when Ball State’s push for immersive learning projects inspired Beth Turcotte, a professor of theater and dance. She assigned her students the task of creating a musical, and they threw themselves into the task, proposing as source material Indiana expat Cathy Day’s acclaimed novel “The Circus in Winter.”

Student Ben Clark took on music-writing duties while the rest of the class set to work adapting the multigeneration, century-spanning stories that made up Day’s book. Turcotte said she drove the project “from the back seat.”

Day, to her credit, didn’t expect fidelity to her creation.

“It’s good that I visited the students early in the process,” said the novelist, who has since joined the Ball State English faculty. “In the first version, they were trying to honor and be faithful to the whole book. I don’t know a lot about musical theater, but I knew that being faithful doesn’t necessarily produce the best movies or plays.”

“It’s good that I visited the students early in the process,” said the novelist, who has since joined the Ball State English faculty. “In the first version, they were trying to honor and be faithful to the whole book. I don’t know a lot about musical theater, but I knew that being faithful doesn’t necessarily produce the best movies or plays.”

She told the students to do what they needed to do to make it good as a musical.

And they did, leading to a series of workshops and a full production by Ball State Theatre, which included a complex elephant puppet that cost about $8,000 to construct.

So enthusiastic was the reception that Turcotte explored ways to take the show beyond Muncie. When she was told her department couldn’t afford sending a show of that size to the American College Theatre Festival, she raised $40,000 from grants and other sources.

“Circus” went on to be named an Outstanding Production of a New Work by ACTF.

Beyond Muncie

The festival helped put the show on the radar of musical theater professionals.

Donna Lynn Hilton, a producer with 22 years of experience at Goodspeed Musicals, encountered “The Circus in Winter” while loading her dishwasher.

She was judging entries in the National Alliance for Musical Theatre’s annual festival when the rootsy score grabbed her attention. The guitar-heavy, banjo-tinted music certainly didn’t sound traditional Broadway, but with Sting, Carole King, ABBA and Motown represented in legit New York theaters today, the definition of Broadway music is hardly fixed.

Intrigued by what she heard, Hilton put the dirty dishes aside, took out the script and fell for the “amazing potential” of the show.

“I wanted desperately to be a part of it,” she said. At the NAMT festival in New York City, excerpts were given an attention-getting presentation. Helping matters: Broadway star and friend of Ball State Sutton Foster playing a key role.

Hilton’s desire to bring the show to Goodspeed solidified. She wasn’t alone. By that time, the show had come to the attention of Sean Cercone, a Chicago producer recently relocated to New York City, and Ken Dingledine, a Ball State grad serving as vice president for theatrical heavyweight Samuel French Publishing.

After striking a deal with Ball State, the pair formed Center Ring Theatricals, a company whose sole mission was to maximize the impact of “Circus”—meaning a return on not only their investment, but also that of Ball State, Turcotte, Day and others who own a piece of the intellectual property.

“Our dream—everybody’s dream—is to get to Broadway,” Cercone said. “We are trying to create a value-added product that’s going to have an impact on the marketplace and be able to generate revenue on a large scope. The only way to do that is to get the show on Broadway.”

At the first table reading for Goodspeed Musicals’ Connecticut production of “The Circus in Winter,” composer/lyricist Ben Clark (with guitar) and company read—and sing—the newly revised script. (Photo courtesy of Goodspeed Musicals)

At the first table reading for Goodspeed Musicals’ Connecticut production of “The Circus in Winter,” composer/lyricist Ben Clark (with guitar) and company read—and sing—the newly revised script. (Photo courtesy of Goodspeed Musicals)Two key requirements for that leap: further development of the material, and money.

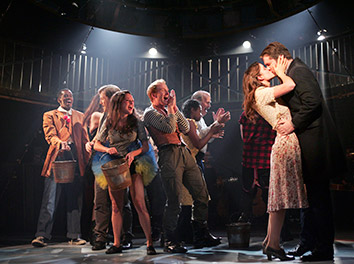

Goodspeed (with Center Ring contributing an undisclosed amount) staged a roughly $500,000 professional workshop production at its Norma Terris Theatre in Chester, Connecticut, inviting potential producers, investors, and interested regional theaters.

What they saw was different in many ways from the Ball State production: A new writer, Hunter Foster, was added to the mix to, in Turcotte’s words, “take the 14 student voices … and streamline it into one voice that matches Ben’s music.”

More than just tweaking the script, Foster added a character not in the previous production or in the original novel, created a more solid through-line, and tried to give the lead character—circus proprietor Wallace Porter—a more central role in the episodic story. Gone, too, was the elephant puppet.

Also key in the creation of the show at Goodspeed: Director Joe Calarco, who has worked at many of the leading regional theaters in the country; choreographer Spencer Liff, from Broadway’s “Hedwig and the Angry Inch” and TV’s “So You Think You Can Dance”; and Tony-winning lighting designer Donald Holder (“The Lion King”).

Whether the changes were successful will be determined by the producers and creative team—which may or may not continue with the production. And don’t look for reviews: Critics are asked not to review Goodspeed’s developmental works since the show changes day by day.

The producers do solicit input from the crowd. At Ball State, “Circus” had a home-court advantage, with friends and family of the performers/creators overwhelmingly enthusiastic. It also played to a younger demographic in Muncie.

The producers do solicit input from the crowd. At Ball State, “Circus” had a home-court advantage, with friends and family of the performers/creators overwhelmingly enthusiastic. It also played to a younger demographic in Muncie.

“Here,” said Turcotte, “they’re all my age or older. At the end of a scene, they want a tap dance.”

You won’t find tap dancing in “The Circus in Winter.” Hilton said it’s “darker than most of what we do here” (concurrent with the run of “Circus,” Goodspeed was producing the very mainstream Irving Berlin tuner “Holiday Inn” on its main stage—see review on page 33).

Big Top bottom line

Goodspeed’s “The Circus in Winter” completed its run Nov. 16. So what’s next?

For one, lots of conversations with those potential producers/investors who made the trek from New York and beyond to see it.

Center Ring Theatricals is tight-lipped on how much money they’d like to raise, how much has already been raised, what share Ball State still owns, and who those investors have been—citing legal issues with disclosing such information.

It’s no secret, though, that money is needed to continue developing the show—and that Indiana investors have already joined the team.

Even seasoned producers will say the odds are against a Broadway investor’s making money. Shows can close the day after they open for lack of strong reviews and good word of mouth. For every “Wicked,” there are far more shows such as “Hands on a Hardbody,” “Big Fish,” or even the high-profile “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark” that don’t earn back their costs.

Even for those that do, the price is steep and the road can be long. Last year’s Tony-award-winning Best Musical, “A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder,” for instance, needed to attract 130 investors of $25,000 to $850,000 each to amass a total of $7.5 million by opening night.

Investments can’t come from just any lucky lottery winner. Federal rules dictate that a Broadway investor must earn at least $200,000 a year (or $300,000 jointly), have a net worth of over $1 million, or meet other suitability standards. And those in it to see their names posted outside a Broadway theater should be warned: Each show sets a minimum investment for such credit.

What happens if someone does meet the criteria and ponies up a check? According to Center Ring’s Cercone, they buy a share in the show. But how much of a share isn’t certain until the entire capitalization need is determined.

Whatever happens to “The Circus in Winter,” musical theater development will continue at Ball State.

Sparked by the show’s success, Turcotte and company launched the Discovery New Musical this summer in which submissions from around the country were vetted by Ball State students with three given script-in-hand readings and one selected for a full production next season. The program was a hit, with more than 130 submissions—well ahead of expectations.

Turcotte is now working on an international musical festival.

“When I get done with that,” she said, “I’m retiring.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.