Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowImagine seeing the price of gas drop 50 percent, then finding out you couldn’t take advantage because of a law that excluded drivers who lease their vehicles or whose fuel tank is on the wrong side.

That’s pretty much the experience of most would-be solar energy users. The price of panels has plummeted in the last few years, but that doesn’t mean everyone who wants solar for their home or business can have it. Only a quarter of all rooftops in the United States are suitable for hosting solar panels, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Even a big, flat, roof open to full sun isn’t going to work if the property owner won’t allow it.

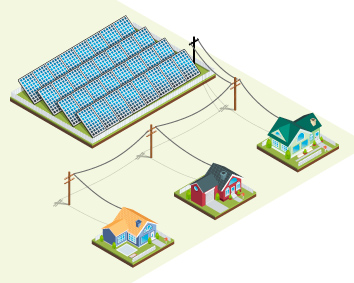

One way around the problem is through so-called community solar gardens. The concept, which is catching on in a few states and in rural Indiana, allows electricity customers to benefit from solar energy without hosting panels on their property. A group of customers or an electric utility will buy a solar array, place it in an ideal location, and tie it into the grid. Customers who own panels, or who subscribe to the utility’s program, can then receive credit on their bills for the energy the garden produces.

The concept, also known as virtual metering, has the potential to dramatically increase solar’s share of energy production, and it represents a huge selling opportunity for the panel-installation industry. But executing the concept requires cooperation from utility companies and state regulators.

At least 24 states allow virtual metering to some extent, according to the Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency at the North Carolina Solar Center. In Indiana, the legal authority for retail customers to set up virtual metering with their own equipment is not clear.

In states where virtual metering is under way, a group of condo owners could work with someone who owns a vacant lot or warehouse a few miles away to install solar panels for their benefit, said Laura Ann Arnold, president of the Indiana Distributed Energy Alliance, which represents solar installers and other renewable-energy businesses. Or, a business could install an array on its property and allow people who live in the area to buy into it.

Rural demand

Rural electric membership cooperatives are leading the charge on community solar in Indiana.

Tipmont REMC, which serves an area between Lafayette and Crawfordsville, launched the first project last fall with 240 panels producing about 100 kilowatts at the co-op headquarters in Linden.

Several more REMCs in northern Indiana are considering them, said Jim Straeter, whose Ag Technologies Inc. installs solar on farms and rural residences.

Rochester-based Ag Technologies saw $2 million in solar-related revenue last year, and Straeter expects that to double this year. He thinks community-solar projects could easily account for a quarter of all his solar business.

“I think that business model is going to develop fairly quickly,” he said.

A rural co-op’s mission is to respond to member needs, and Tipmont’s 22,000 mostly residential members have shown a strong interest in renewable energy, said Corey Willis, membership engagement manager.

Plus, Tipmont’s 100-kilowatt garden, enough to power seven to 15 homes, means the utility, which doesn’t own its own power plants, won’t have to buy as much energy on the open market, Willis said.

“Every kilowatt generated is one less we have to buy,” he said. “In that regard, everybody wins.”

Tipmont REMC is pitching its community solar program as a hedge against rising energy costs. Members can buy a 25-year subscription for $1,250 per panel.

The utility tells its customers to expect monthly billing credits worth $5 per panel and estimates they’ll avoid paying an additional $2,280 for electricity over the 25 years.

Tipmont could have simply installed the panels and kept the benefits of the energy generation for itself, Willis said. Instead, the co-op is passing the benefits to its members, who will receive credit for their solar-generated energy at the full retail price of electricity, which is slightly less than 10 cents per kilowatt-hour.

If customers move within the co-op’s service area, they’ll be able to take the credits with them, Willis said.

Most Hoosiers are served by investor-owned electric utilities, which are overseen by the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission. The two utilities covering central Indiana, Duke Energy and Indianapolis Power & Light Co., have yet to step forward with community solar proposals.

“We believe we first need to address the right policy for customer-owned generation,” Duke spokeswoman Angeline Protegere said.

Investor-owned utilities are supporting a controversial House bill that would allow them to pay lower rates per kilowatt-hour to customers who generate excess, or “net,” energy with their small-scale, on-site systems. Solar advocates believe the bill would be a step back for net metering, but utilities say they need a way to ensure they have enough revenue to support a reliable grid.

IPL spokeswoman Brandi Davis-Handy said the utility is “supportive of the concept” of community solar but that there are “challenges,” including defining the legal structure for it to occur and identifying strategic locations on the grid.

IPL is weighing whether to launch its own community solar program because it would allow for broader participation by customers, including renters, Davis-Handy said.

Indiana Michigan Power, which covers Fort Wayne, Muncie and South Bend, has a pending request to allow customers to buy blocks of energy from solar arrays owned by the utility, IURC spokeswoman Chetrice Mosley said.

The demand for solar in rural areas might come as a surprise, but Straeter, who also owns a chain of farm-equipment dealerships, said the economics of it are even more favorable to farmers than homeowners because the panels can be depreciated for tax purposes.

Ag Technologies has been selling so many of its ground-mounted systems in rural Fulton County that renewable-energy use charted for the first time.

“Renewable was zero. Now it’s slightly above 1 percent,” Straeter said. “That happened in about a year and a half.”

Farmers typically install their arrays near energy-intensive operations like dairy barns or grain driers, but community solar also would allow them to make use of far-flung, untillable ground, Straeter said.

A piece of land that’s not good for farming might be perfect for solar, but often it’s too far from the property owner’s operations to justify the cost of wiring it in, Straeter said. Virtual metering could help overcome that hurdle because wiring doesn’t have to run to the panel’s owners.

Ag Technologies is selling to rural homeowners, too. By urban standards, the typical backyard installation sounds enormous. Straeter’s 3,300-square-foot home, for example, requires about 1,000 square feet of panels. However, it’s heated and cooled with geothermal; homes with less-efficient systems would require an even larger array of panels.

But many a house in the countryside is surrounded by land that’s not in the hands of the homeowner, Straeter said. “Customers have not gone ahead with solar for that reason.” Again, community solar gives Straeter a way to overcome a common objection to the sale.

Legal question

For the community solar market to really take off, Indiana would have to allow customers to set up their own arrays—without a utility’s involvement, Arnold said.

The legality of that type of arrangement remains untested in Indiana, Mosley at the IURC said. In Indiana, utilities are granted exclusive territories, and the question is whether panel owners who set up virtual metering are acting like utilities, thus impinging on their territory.

Some might argue that is the case because the panel owners are selling energy to a group of retail customers, Mosley said. Others would say solar gardens don’t conflict with utilities because they operate under contractual arrangements among specific customers, not selling energy to the public at large, she said.

So far, no one with deep enough pockets has pressed the legal case for virtual metering, Arnold said. “We’re not close to being there.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.