Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAn office in early 19th century Indianapolis was populated almost entirely by men using quill pens to make entries in mammoth ledgers spreading across oak desks. Office furniture consisted of hard-backed wooden chairs and massive oak desks.

But in the post-Civil War era, offices began to change dramatically—and those changes continued through today when interactive whiteboards and massive monitors dot open-concept office spaces.

It’s not just office furniture and equipment that have changed over the past 200 years. So have commercial printers, employment agencies and recycling—all parts of an office products category that is typically forgotten in city history but without which business would soon grind to a halt.

By the late 1800s, offices—while still populated largely by men—included elaborate Victorian desks with pigeonholes and drawers with ornamental handles. Clerks made their entries and affixed their signatures to documents with fountain pens dipped in a refillable ink bottle. As the century progressed, the clack-clack-clack of typewriter keys became a more common sound.

Into the 20th century, the Indianapolis office began to take a shape that would be familiar to 21st century employees. Women began coming into the office as a result of labor shortages during two world wars. Typewriters were streamlined and then electrified. Telephones became a fixture on every desk. Until the 1960s, office reproduction was done on mimeograph machines or sourced out to companies such as Bates Inc. and Marbaugh, which produced Photostats and blueprints. That changed in the 1960s and 1970s, however, as mass-produced xerographic machines began appearing in Indianapolis offices, making copies of documents a simple and inexpensive procedure. Administrative assistants–called secretaries–took dictation from executives or foot-pedal-operated reel tape recorders.

Office furniture in the second half of the 20th century transitioned from wood to a combination of wood, plastic and metal. Fabric-covered partitions became the rage late in the century and divided office space into personal cubicles. Business Furniture LLC, started by C.S. “Cy” Ober in the Indianapolis Warehouse District in 1922, has represented international office furniture manufacturer Steelcase and its predecessors since the firm opened its doors at 42 S. Pennsylvania.

The real automation of the Indianapolis office place began in the last quarter of the 20th century. Copiers became more sophisticated. Typewriters and cumbersome hand-cranked adding machines disappeared, replaced by mainframe and later desktop computers. The silicon chips that provided the memory and capacity for the office computer began a decades-long journey of packing more and more memory and capacity onto smaller and smaller chips.

Office communications underwent a seismic change. Facsimile machines, developed by the U.S. military in the 1960s, with paper rolls as long as eight feet and weighing 30 pounds or more, became smaller and suitable for placement in the office. With the proliferation of desktop and laptop computers and the continuing growth of the Internet, email became the preferred method of business communications. Office printers–initially daisy wheel and later laser and inkjet–supplemented or replaced the office computer. Cell phones, and later smart phones, replaced landline telephones in smaller businesses and became ubiquitous in all work places. Among younger workers, email was supplanted by social media and texting.

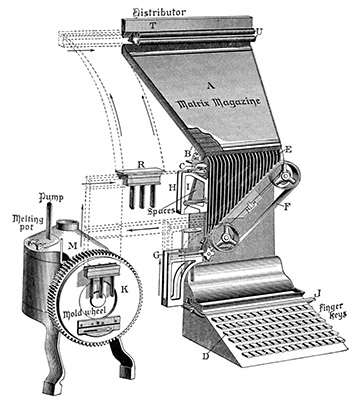

Office equipment and office furniture distributors and dealers in central Indiana have worked hard during the past two decades to help customers transform work places with technology. Commercial printers, too, have seen their businesses change dramatically during the past century-and-a-half. From the mid-19th century to the mid-20th century, commercial printing changed little. Printing jobs were both hand-set and machine-set on a Linotype and then printed on a letterpress, which made an impression on each sheet of paper in the job, whether it was something as small as a business card or as large as a two-page newspaper spread. One of the city’s largest commercial printers 100 years ago was Bobbs-Merrill, a noted national book publisher.

In the 1960s and the 1970s, letterpress printing went the way of the standard upright typewriter, as commercial printers switched to offset printing. Jobs were pasted up, photographed, and the negative burned onto a thin metal plate that wrapped around a cylinder on the press. The press left a sheen of ink on each piece of paper that passed over and through it. Today, printing jobs are set up digitally and printed on increasingly sophisticated offset machines.

Today’s major Indianapolis-based commercial printing firms take specialization to a degree undreamed of in the past. Allison Payment Systems LLC, which traces its origins to the 1880s, has evolved from a coupon payment booklets developer and manufacturer into a full-service transactional data processor and mail provider. HardingPoorman Group is one of North America’s leading commercial graphics providers. Sport Graphics Inc. has built a $26 million business in signage, display and event décor.

The change in how firms purchase and use sophisticated office systems has created niche markets for office equipment dealers. Indianapolis-based Cannon IV, for example, focuses on document management. Cannon IV works with clients to reduce costs by optimizing infrastructure, managing the print environment and streamlining digital workflow.

Typewriters were streamlined and electrified and sped word processing. (IBJ file photo)

Typewriters were streamlined and electrified and sped word processing. (IBJ file photo)Another specialty target for the office products marketplace is the modern employment agency. A far cry from the “temp agencies” of the mid-20th century, employment agencies work with customers to provide specialty personnel in all areas of the customer’s business, including accounting, engineering, IT, life sciences, logistics, marketing and other areas. Services can included clerical to call center to professional skills.

The history of recycling in Indianapolis goes well back into the 19th century. In the years following the Civil War, the city supported a large community of peddlers, who searched Indianapolis alleys for rags, scrap iron and other metals including tin and brass; rags were in high demand during the period because they were recycled into pulp for high-quality paper. Driving horse-drawn wagons, scrapping provided entrepreneurial employment for many of the city’s Jewish immigrants arriving from Eastern Europe.

One major Indianapolis scrap iron and metal operation has long ties with northeastern Indiana. In 1943, Irving Rifkin purchased his first scrapyard, in Fort Wayne, and he and his sons grew it into a major recycling and waste removal business. They renamed the company OmniSource in 1983 and sold the business to Fort Wayne-based Steel Dynamics Inc. in 2007 for $1.1 billion.

Trash removal became a major business in the late 20th century, and today, Republic Trash Services of Indiana and Ray’s Trash Service Inc. are the largest recycling firms operating in the Indianapolis area. Ray’s can trace its history to 1965 when Ray and Barbara Matthews purchased their first trash removal truck.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.