Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowI’m reading Meredith Willson’s “The Music Man,” one of the classics of the Broadway musical canon.

But some things—lots of things, actually—aren’t quite right.

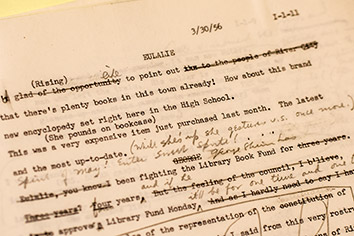

The iconic song “Trouble in River City” is nowhere to be found. “Seventy-Six Trombones” has a few extra verses (including reference to a glockenspiel). And remember Winthrop, the “Gary, Indiana”-singing kid with the lisp? Not only doesn’t he get the song, he can’t walk or talk.

I stumbled into this bizarre alternative Iowa courtesy of a box of early “Music Man” drafts in the Great American Songbook Archives & Library at the Palladium. Since the first boxes arrived in 2010 (and were parked in storage units until the complex’s 2011 opening), the collection has grown to over 100,000 items—with 40,000 pieces of sheet music alone.

I stumbled into this bizarre alternative Iowa courtesy of a box of early “Music Man” drafts in the Great American Songbook Archives & Library at the Palladium. Since the first boxes arrived in 2010 (and were parked in storage units until the complex’s 2011 opening), the collection has grown to over 100,000 items—with 40,000 pieces of sheet music alone.

My host is archivist—and lone full-time employee—Lisa Lobdell, who is tasked with not only organizing the collection, but also determining the desirability of items to be added.

Treasures in the Great American Songbook archives include recorded materials. (IBJ photo/Eric Learned)

Treasures in the Great American Songbook archives include recorded materials. (IBJ photo/Eric Learned)There was no question when it came to accepting the bounty of Willson’s papers or the musical arrangements of Ray Charles (no, not that Ray Charles—the musical consultant and arranger who worked on “The Muppet Show” and “The Kennedy Center Honors”). There are more

decisions to be made, though, when an out-of-the-blue telephone call comes from someone wanting to unload Great-Grandma’s box of sheet music—once as ubiquitous as VHS copies of “Titanic” or “Thriller” LPs.

Even the stuff that seems special often isn’t. While a collector or fan might treasure an autograph, a simple signature isn’t of much value to a collection such as this. What are important are items that might help historians, academics and others piece together the stories behind the songs and their composers—a list of casting choices, perhaps. Or personal correspondence with fans. Sometimes that means, as happened recently, getting to work cleaning mold off reel-to-reel tapes (Lobdell’s wish list includes a freezer to better preserve such recordings.) Other times it means finding relics that reveal as much about society as music. You might have a dusty 45 rpm recording of “Rock Around the Clock,” but you probably haven’t seen one that was clandestinely recorded in Russia on a disc cut out of X-ray film with a cigarette burn serving as the spindle hole.

The collection includes shelves of CDs, albums and books, too, but the papers are central—boxes and boxes of papers carefully coded by staff and a team of passionate volunteers. That’s how I discovered the early drafts of “The Music Man.”

Great American Songbook Library archivist–and sole full-time employee–Lisa Lobdell examines a recording made on Soviet X-ray film. (IBJ photo/Eric Learned)

Great American Songbook Library archivist–and sole full-time employee–Lisa Lobdell examines a recording made on Soviet X-ray film. (IBJ photo/Eric Learned)The trivia is fun (no, I didn’t know the show once included a song called “Don’t Put Bananas on Bananas”), but there are deeper lessons here. The “Music Man” drafts show the tremendous amount of work that went into creating something that comes across (in a good production) as effortless. The show, as evidenced here, didn’t burst spontaneously from Willson’s brain. It evolved relentlessly and improved line by line, verse by verse, thanks to a diligent artist/craftsman with a willingness to throw out what wasn’t working.

Bonus: There’s something moving about the uneven lines created by old typewriters—the way the H in Harold is always a little higher than the other letters, perhaps because of delayed or overenthusiastic pressing on the caps key.

The Songbook Foundation also offers free exhibitions, including, opening Feb. 15, “The Great Indiana Songbook: Two Centuries of Hoosier Music,” spanning classical to pop to heavy metal. The exhibition room is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday.

As I dig into the collection, I hear spirited music coming from volunteer Janice Roger (by profession, the cantor for Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation). She tells me we’re listening to the overture to 1903’s “In Dahomey,” which some quick research reveals was the first Broadway musical written by, composed by and starring an African-American cast.

Later, I get caught up in the world of Hy Zarat, who wrote the lyrics for “Unchained Melody” and, I learn, also penned such lesser-known tunes as “Molecules, Molecules,” “How Does Radar Work?” and “How Does a Cow Make Milk?” for a group of kids’ recordings that seem like an early run at “Schoolhouse Rock.”

Sample lyric: “You can get good milk from a brown-skinned cow/the color of the skin doesn’t matter no how” and “Columbus said, ‘Si, Si Signor’ and Lafayette said, ‘Oui’/But when Uncle Sam said, ‘Will you help?’/They both said ‘Yes siree.’”

Pretty cool for 1947.

The Palladium has offered a parade of concerts dedicated to such songwriters (upcoming shows include Cheyenne Jackson on March 5 and Denzel Sinclaire on April 16). It has also created the Songbook Academy and high school vocal competition (returning in July), and lured stars and songwriters here for the Songbook Hall of Fame (with another batch in October). What’s stored here on the top floor of the Palladium—and what will someday form the basis of a Great American Songbook Museum—is a lesser-known but equally important piece in a commitment to keeping this music alive. I’d happily spend weeks free-associating through the collection.

Roger opens another box with items to be organized. Inside: materials related to actress Alice Ghostley, best known as shy witch Esmeralda on the TV’s “Bewitched.” Apparently, Ghostley got her big break in the Broadway revue “New Faces of 1952,” where she starred alongside other newcomers Eartha Kitt, Paul Lynde and Melvin (later shortened to Mel) Brooks.

I’m tempted to look up the actress’ other Broadway credits, but not before making a note that I’ve got to find a recording of “Don’t Put Bananas on Bananas.” I’m sure there’s one here somewhere.•

__________

This column appears weekly. Send information on upcoming arts and entertainment events to [email protected].

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.