Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowFor years, Indiana Repertory Theatre’s ads carried the line “World Class Theatre. Made in Indiana.”

Hyperbole? Not when applied to IRT’s production of August Wilson’s “Fences” (through April 3).

This outstanding production proves that an impeccable cast, a first-rate script, and top-notch design under the guidance of knowing direction can create work right here that holds up to the best anywhere. I try not to use this column as a bully pulpit but, in this case, I urge you, cajole you, beg you to see what IRT has built from the foundation of Wilson’s outstanding, Pulitzer-winning script.

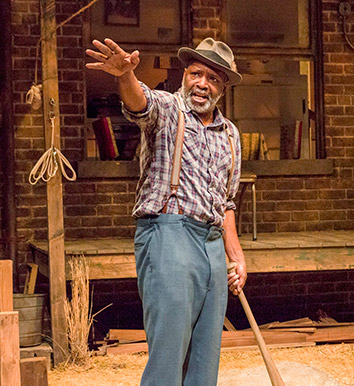

At the volcanic center of Wilson’s 1987 play is Troy Maxson (David Alan Anderson, always strong but never better), whose life has included both jail time and hitting home runs against Satchel Paige in the Negro Leagues. The year is 1957 and the setting—the richly detailed creation of scenic designer Vicki Smith—is the back yard of the home Troy shares with his wife, Rose (Kim Staunton, powerful), and son, Cory (Edgar Sanchez). The play opens with laughter as Troy banters with Rose and fellow sanitation worker Bono (Marcus Naylor, subtly heartbreaking).

Matters get more serious when we meet Cory and learn of Troy’s open hostility to his son’s football-playing ambitions. It’s through their relationship that we begin to see Troy’s anger which—even when disproportionate or misdirected—comes from a real place. With a work ethic forged from a life lived, Troy strives to do what he thinks is right, but isn’t conscious of the collateral damage those actions caus e. In a just theatrical world, this rich, multidimensional character would be as well-known as Willy Loman from “Death of a Salesman” or Blanche DuBois from “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

e. In a just theatrical world, this rich, multidimensional character would be as well-known as Willy Loman from “Death of a Salesman” or Blanche DuBois from “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

Even though the play has been staged here before (by IRT in 1995-1996 and by the Phoenix five years earlier) and has become a regional-theater staple, I’ll assume many are seeing it for the first time; I’ll refrain from sharing more plot details.

Suffice it to say that “Fences” deals in power—or lack thereof. Its characters are defined, in part, by their efforts to create a world they can at least partially control. The fence of the title is unfinished as the play opens, representing an effort to control what’s going on in Troy’s world. But he’s not alone—others are also trying to control their lives and, unlike in lesser dramas, words said and actions taken have a decided impact on later words and actions. Far more than a simple father/son drama, “Fences” offers a wealth of vibrant, riveting relationships.

An expert production such as this can reveal flaws in even the best plays. Here, though, a long-ish final scene and a few too many uses of baseball and fence-building symbolism are hardly worth noting.

“Fences” is part of Wilson’s cycle of 10 plays, each set in a different decade of the 20th century. But no knowledge of any of those plays is necessary to appreciate this, one of the earliest and most straightforward of the series.

Anything by Wilson is worth seeing, but anything this strong is a must-see.

__________

A trio of strong performances from local theatrical anchors Jen Johansen, Bill Simmons and Rob Johansen enhance Steven Dietz’s “On Clover Road” (through April 10), a thriller that marks the latest in the Phoenix Theatre’s dedication to new work via the National New Play Network.

Set in a seedy, abandoned hotel room, the play concerns efforts of a distraught mother (Jen Johansen) and a hired deprogrammer (Rob Johansen) to kidnap a young woman who has been taken under the wing of a charismatic “prophet” (Simmons).

Don’t take my word, though, on any of the details stated in the preceding paragraph. This is a thriller in which the rug is consistently pulled out from under the audience, making it question assumptions made about its characters just moments before.

The twist-heavy plot of the Phoenix Theatre’s “On Clover Road” involves a distraught mother, an edgy deprogrammer, and a young woman allegedly held by a cult. (Photo courtesy of Zach Rosing)

The twist-heavy plot of the Phoenix Theatre’s “On Clover Road” involves a distraught mother, an edgy deprogrammer, and a young woman allegedly held by a cult. (Photo courtesy of Zach Rosing)Such a theatrical game is fun when it works—when the shifts seem to organically develop and the revelations appear to arrive via the characters and not a controlling playwright. The opening scene is particularly effective as the deprogrammer attempts to give the mother the rules of the game and fault lines in her story begin to be revealed.

Things slow down a bit—and the writing becomes less lean and mean—when the young woman is brought into the picture and the revelations start to become more contrived than compelling. Draining away some of the potential edge is the overly bright lighting, consistently throwing distracting shadows on the grimy walls.

The cast gamely adds urgency even when the plotting feels rote. The denouement of an effective thriller should feel both surprising and, in hindsight, inevitable. There’s a hint of that here, but it isn’t fully developed. Instead, the climax comes down to a maybe-she-will/maybe-she-won’t act of a character we know little about.

Such a coin-flip might be suspenseful in the moment, but it isn’t wholly satisfying when it’s over.•

__________

This column appears weekly. Send information on upcoming arts and entertainment events to [email protected].

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.