Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowStartups in Indianapolis often have barely grown after five years in business, according to a new study, a development that’s rekindled criticism of the local venture capital landscape and highlighted the conservative way some firms here are run.

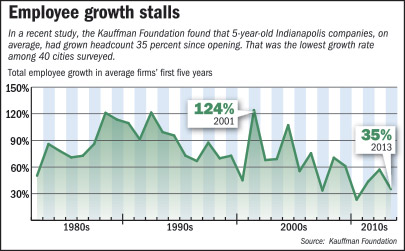

According to 2013 data—the latest available—from the Kauffman Foundation’s “Growth Entrepreneurship” report released this month, Indianapolis-area businesses that had started five years earlier grew their employee headcount only 35.3 percent, or an average of 6.9 employees to 9.4 employees.

That was the lowest growth rate among the 40 metro areas surveyed.

Based on rate of employment growth and two other indicators, Indianapolis ranked 20th overall in the study, which measures the performance of cities with respect to high-growth companies. Its poor showing in the employment category is the main reason Indianapolis dropped from its No. 11 spot in 2015.

Weeks

Weeks“I think we obviously need to keep striving for improvement there,” said Cameron Weeks, CEO of call-center-software company Sharpen Inc. “Some of the biggest things that happen in industries happen when you set out to disrupt a very large market, and that takes large numbers of people.”

Still, some think employee growth is not the be-all and end-all.

“I don’t think it’s a bad thing on all counts; I think looking at data in a vacuum is a bad thing,” said Brian Powers, CEO of 3-year-old legal tech firm PactSafe LLC. “Headcount is not the only indicator of success.”

The report doesn’t mention possible factors behind the city’s last-place ranking in employment growth, but some observers think one factor is a scarcity of venture capital, which is a key fuel for hiring people.

Powers

PowersFor investors and other stakeholders, the fact that new Indianapolis companies grow more slowly here could indicate that firms are efficient with their human capital—doing a lot with a little, some observers said. But it could also be a sign firms aren’t able to move as quickly or as forcefully as needed to become a sizable industry player, one worthy of going public or getting acquired.

“Let’s take Uber for example—they’re building a sharing-economy platform,” said Weeks, referring to the $60-billion-plus ride-hailing company. “To do something of that scale, no matter who you are or how effective you are, it takes lots and lots of people.”

The Growth Entrepreneurship report is part of a trio of annual Kauffman reports that survey entrepreneurship across the United States. This report looks at several industries that have fast-growing companies inside and outside of technology.

“High-tech is not a prerequisite for high-growth,” said E.J. Reedy, a Kauffman Foundation senior scholar and co-author of the report. “While tech industries continue to have a strong presence among high-growth companies, growth comes from a wide range of sectors—from food and beverage, to retail, to government services.”

One bright spot in the study was Indianapolis’ performance in the “share of scale-ups” category, where it ranked fourth. That category measures the percentage of companies with at least 50 employees by their 10th year. In Indianapolis, 2,260 out of every 100,000 companies 10 years old or younger, or2.26 percent, fit that bill.

The report debuted this year, but it’s based on data going back to 1977. Kauffman, which generated 2015 and 2016 rankings for comparative purposes, found Indianapolis’ employment growth rate for the five years ending in 2012 was 57 percent, but slipped to 35 percent in the five years ending in 2013.

Grave

GraveKauffman said Indianapolis had 2,712 brand-new companies in 2008, with about 6.9 employees each, and 2,202 5-year-old companies in 2013, with about 9.4 employees each.

Not yet arrived

Observers chalked up the disappointing headcount growth partly to the reality that outside capital doesn’t flow as abundantly here as it does in some other markets.

“Until we’re willing to loosen the reins on the pocketbooks more for a broader spectrum of companies, I think we’re going to see job growth remain near the bottom,” said Crystal Grave, CEO of event-planning marketplace company Snappening LLC.

“Because you can’t make great jobs for people at $50,000-plus a head … at the beginning of a technology company when you’re getting your first customer.”

The National Venture Capital Association said that, last year, venture capitalists pumped just under $55 million into the Indianapolis area, which pales in comparison to cities like Chicago, which saw $1.1 billion in funding. Austin, Texas, whose metro population is similar to Indianapolis’, pulled in $740 million.

“We’ve got plenty of people who can stroke small checks around here, so I think it’s not a problem for early-stage seed rounds,” said J.J. Thompson, CEO of cyber security firm Rook Security.

“But I do think that, until we start seeing Series A rounds that average over $10 million, we haven’t really arrived as having a venture community that can sustain the type of growth that we need to see continuous wins.”

The venture capital firm Hyde Park Venture Partners last year opened an Indianapolis office to help solve the so-called Series A crunch—the shortage of funds for firms seeking their first round of institutional equity.

And out-of-town venture firms, including Los Angeles-based Kayne Partners, are turning newfound attention to Indianapolis, drawn partly by the lower valuations of companies here compared with bigger markets.

Thompson

Thompson“Indy is one of the key underserved geographies we are targeting,” Kayne Partners’ Doyl Burkett said in an email, “and we expect to visit approximately once every three or four months going forward.”

But funding from out of town isn’t a complete substitute for local funds, observers said, since securing that money often is arduous and time-consuming.

Tough time

Local venture dollars tend to go to business-to-business software companies.

Successful acquisitions and other exit events for marketing-tech companies like ExactTarget and Aprimo have yielded investors who, naturally, tend to invest in what they know. But few investors here are willing to make bets in software companies targeting consumers, for instance, leaving such firms with few resources to get ideas off the ground.

“I think the biggest challenge we’ve seen is, we are more of a consumer-product company, and that’s just not the culture here,” said Aimee Kandrac, CEO of WhatFriendsDo LLC. The website and application allows people to manage help from others during life-changing events involving loved ones.

Kandrac built the platform in 2005 while working at a not-for-profit. She made the company her full-time job in 2013. Today, it has six employees and 60,000 users across the world.

After about 10 months of pitching investors, Kandrac last summer landed $500,000 in growth capital. Securing the money was no easy task, she said, but if she had a marketing tech or biotech company, “everybody would help me.”

Rook Security’s Thompson faced similar headwinds. He said that, when his cybersecurity firm moved here from California in 2009, it had trouble getting interest from marketing-tech-oriented investors. So he bootstrapped, growing the company slower than he would have with a capital injection.

Today, local investors are interested in Rook, but they don’t necessarily have the means to write the million-plus-dollar checks that the $12-million-in-revenue company is looking for.

“I think it’s going to take another four ExactTarget-sized exits—but outside of marketing tech—before we actually start to see real local venture capital funds being invested,” Thompson said.

For some companies, slow employee growth is not the result of a lack of cash—it’s a conscious decision.

Powers, the PactSafe CEO, said he has seven employees and plans to add three by the end of July. The company has raised $1.2 million, and he’s satisfied with the pace of growth.

“We have pretty significant revenue growth without corresponding headcount growth,” Powers said, noting that the company has 64 paying customers, triple the number at the start of the year.

“You look at some of the fundraising trends on the coasts, where companies get big valuations very early, raise a lot of money, and all that goes into headcount, but sometimes it might not have a huge dent on revenue and profitability.”

Some Indianapolis companies have decided against raising venture capital, even though outside cash could accelerate growth.

Transportation-software firm DoubleMap Inc., founded in 2011, is one example. It has 30 full-time and 10 part-time employees. And email-marketing firm Delivra Inc., founded in 1999, has used only reinvested profits to fuel growth. It has 41 employees.

The lack of outside money gives company founders greater control.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.