Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn Gov. Mike Pence’s first State of the State address, the Republican called on Hoosier leaders and communities to make career, technical and vocational education a priority.

Schools, he said, “should work just as well for our kids who want to get a job as they do for our kids who want to get a college degree.”

Nearly four years later, as Pence runs for higher office and prepares to leave the Statehouse, more students are enrolled in career and technical classes, more are earning career-based certifications before graduation, and more money has been distributed through grants for industry-focused education.

The progress is thanks in part to an increased national focus on career and technical education. But it also follows that 2013 speech, in which Pence announced an initiative that included the Indiana Career Council and a network of 11 regional organizations known as Indiana Works Councils.

Burton

BurtonThe Works Councils are meant to bring educators and employers together on the regional level, making sure local career and technical training is in line with employer needs. The Career Council has a similar focus on a statewide level.

“The Career Council has certainly brought a focus to workforce development,” said Brian Burton, president of the Indiana Manufacturers Association.

But educators and business leaders say challenges remain.

Many schools—facing tight budgets—must focus on academic basics rather than expanding programs. And the local councils are all-volunteer, with little or no budget.

Plus, too many students are still enrolled in programs that won’t lead to higher-paying jobs, Burton said.

“We need to have a workforce system that is more demand-driven,” he said.

(Photo courtesy of Walker Career Center)

(Photo courtesy of Walker Career Center)Last year, the largest group of career and technical education students—19 percent—was enrolled in hospitality and human services programs, Burton said. In that sector, he added, “there are very few jobs that make a very good wage for those graduates.”

At the same time, only 4 percent of students enrolled in career and technical education were in manufacturing-specific programs. That’s despite the fact that more than 521,000 Hoosiers worked in manufacturing last year, more than any other industry sector. And those jobs paid an average annual wage of more than $61,000—the highest of all sectors, just edging out the financial industry.

Even more important, a 2015 survey conducted by Katz Sapper & Miller and Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business found that 70 percent of manufacturers said they saw either a “moderate” or “serious” shortage of skilled production workers.

“We have to do a better job of letting the general population—and in particular, young folks in high school—let them know what those opportunities are for rewarding careers and great pay,” Burton said.

By the numbers

According to the Indiana Department of Workforce Development, the number of students participating in career and technical education programs has risen over the past three years.

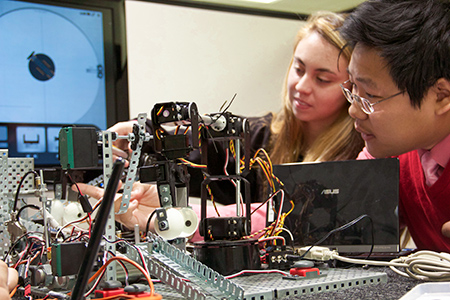

The Walker Career Center offers 20 programs meant to help both students who want to go to work after high school and those planning to attend college. (Photo courtesy of Walker Career Center)

The Walker Career Center offers 20 programs meant to help both students who want to go to work after high school and those planning to attend college. (Photo courtesy of Walker Career Center)In the school year that ended in May, nearly 175,000 students were enrolled in more than 235,000 career and technical classes. That’s an 11 percent increase since the 2012-2013 school year, when Pence issued his challenge.

The number of high school students earning an industry certification or credential is also on the rise, according to the Indiana Department of Education.

During the 2013-2014 school year (the last for which numbers were immediately available), 8,400 graduates had earned at least one industry certification, license or industry-recognized credential. That’s 11 percent more than the year before.

Dual high school/college credits represented the largest group of these credentials, although nearly 800 students earned certified nursing assistant credentials and more than 100 earned welding certificates.

Steve Rogers, director of Warren Township Schools’ Walker Career Center, said he sees a growing awareness of the value of career and technical education among students. On any given school day, 1,300 to 1,600 students from Warren Central, New Palestine, Greenfield and Mount Vernon high schools come to Walker for a portion of their school days.

“We’re seeing a lot more kids that are coming in and seeing, ‘I can be successful as a welder and I don’t have to go to college,’” Rogers said.

The Works Councils and Career Council are probably helping drive this shift, Rogers said, but he can’t say they are the only reason.

For instance, Rogers has seen enrollment in his school’s construction trades program grow from 25 to 60 students over the past three years. But he suspects it’s because the school hired a dynamic new teacher to replace a retiree.

The state also has increased the number of professional credentials high school students can pursue at no cost to them or their school, Walker said.

“It’s hard to say that anything that’s increased is a direct correlation to the Works Council. I think, in general, the public is growing increasingly aware that not every student has to go on to a four-year college to be successful.”

But the DWD says that, since Pence’s 2013 challenge, it has awarded $4.3 million in Career and Technical Education Curriculum grants specifically to boost programs.

For example, the Central 9 Career Center in Greenwood, which serves nine high schools in three counties, received $126,900 in funding to add an industrial repair and maintenance course for students in its advanced manufacturing, electronics, precision machining and welding programs.

The Indianapolis-based Central Indiana Corporate Partnership received $289,050 to offer summer internships to students in advanced manufacturing and logistics.

The DWD, the Career Council and the Works Councils also were sponsors of the 2015 Work and Learn in Indiana Conference, which highlighted successful school/employer partnerships around the state. This year’s conference will be part of the Indiana Sectors Summit Oct. 19-20 in Carmel.

Progress is promising

Decker

DeckerRandy Decker, who retired from the Walker Career Center in May, is a member of the Region 5 Works Council, which covers Marion, Boone, Hamilton, Madison, Hendricks, Hancock, Morgan, Johnson and Shelby counties.

During his 27 years at Walker, Decker taught electronics, computer repair and robotics. He saw a disconnect between education and the workforce and struggled to help his students find jobs after graduation.

“I’d get students prepared, and I didn’t know who to contact,” Decker said.

But last year, Koorsen Fire & Security launched a program for Walker seniors. The students went to Koorsen for classroom lessons and hands-on training on fire extinguishers and fire alarm, security and sprinkler systems. Program graduates earned an industry certificate and had the chance for an internship or a job.

The program has since expanded to include students from other schools.

“I’m convinced that the Works Council helped make this happen,” said Decker, who is now a regional support manager for the Texas-based Robotics Education & Competition Foundation.

Moving forward, Decker said he’d like to see an online resource accessible to both educators and employers. Employers could post available positions, and schools could post information about available graduates and their credentials.

Other Region 5 Works Council members say they’ve seen some progress as well—but also challenges yet to be resolved.

One fundamental problem cited by several members of the Region 5 Works Council: Students, teachers and parents often misunderstand what modern manufacturing is actually like.

McGregor

McGregorAt engine-maker Rolls-Royce Corp., for instance, the floors in the production areas are white, which is easier to keep clean and makes it easier to see that parts, tools and equipment are in the right spot. But a clean and orderly environment isn’t always what comes to mind when people imagine manufacturing, admitted Reginald McGregor, manager of engineering employee development at Rolls-Royce Corp. McGregor is also a Region 5 Works Council member.

Too often, McGregor said, people envision manufacturing as something that leaves employees greasy and worn out. They don’t realize how much the industry has advanced and how deeply technology is integrated into the process.

If people think of manufacturing as dirty and back-breaking work, they won’t likely steer their children or students into the industry, he said.

In addition, some school districts in the area are struggling with basic concerns like making sure they have safe facilities and enough teachers. Schools with that level of need probably aren’t in a position to put added emphasis on career and technical education, McGregor noted.

“Even if we give them a program, who’s going to run that program when they’re trying to find a physics teacher?” he asked.

Another Region 5 Works Council member, Jim Tuerk, expressed frustration that the local group hasn’t had more success.

Tuerk is CEO at Indianapolis-based Aero Industries Inc., which makes tarps and trailer accessories for large trucks. He’s also on the boards of both the Indiana Manufacturers Association and the Mary Rigg Neighborhood Center on Indianapolis’ west side.

“There’s been activity,” he said of the Works Council. “I can’t say we’ve accomplished much. It’s been a frustration for me.”

He noted that the Works Councils are all-volunteer groups, with no budget.

Tuerk said Works Councils in other parts of the state—Columbus, Kokomo, Princeton, Batesville and others—have had success. But he said most of the advances have been in smaller communities, involving large employers—probably because they have more leverage than any single company has in a big city. He also said smaller companies like his don’t have as many resources.

Aero has 155 employees in Indianapolis and 215 total. “One of the challenges is, how do we get small and mid-market companies involved?” Tuerk said. “We know we have to get better, but it’s just harder for a smaller company to do that sort of thing.”

Tuerk and McGregor also said the manufacturing workforce shortage involves problems outside the Works Councils system’s focus.

Transportation problems and drug use, for instance, are barriers to work, McGregor said. People need training, but they also need a way to get to work. And if applicants can’t pass a drug test, they won’t get job offers.

“Is that part of our [Works Council] scope?” McGregor said. “It’s something that needs to be addressed.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.