Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now WEST LAFAYETTE—This is not your father’s Purdue trainer’s room.

WEST LAFAYETTE—This is not your father’s Purdue trainer’s room.

Oh, there is still the row of tables. Lots of tape. Surely, ice always handy. But what’s with all the new-age stuff? What’s with the $100,000 treadmill?

Want to see innovations? Turn your ankle as a college athlete. Or, for that matter, get with the program of trying to prevent turning your ankle.

Doug Boersma, the Boilermakers’ director of sports medicine, is our tour director for what a trainer’s room looks like, circa 2017.

“People at the end of their career in 2003 would come in now and say, ‘Why do you have all this stuff?’ The thing that we’ve really focused on is the pre-hab portion of the student athlete. It used to be—and I still see this when our kids come in on their recruit visits and I talk to their parents—the first thing out of their parents’ mouth in this generation is, ‘Oh you need to avoid this area. Stay out of the training room.’ You hear things like, ‘You can’t make the club in the tub.’ Those are old-school messages.

“The thing I try to enforce to our young student-athletes when they come in as freshmen, we treat more people in here for healthy conditions than injured conditions.”

Boersma

BoersmaStep this way, please. To your left is the anti-gravity treadmill: The AlterG. Huh? Let Boersma explain.

“If you picture one of those bouncy-house big balloons, it’s got that around the treadmill with a hole in the middle of it. You put on a pair of shorts with a zipper and you zip into that hole and the treadmill weighs you. So if you want to run 20 percent less your body weight, it starts filling with air, and that pressure relieves the weight on your lower extremity.”

Windows on the side allow the athlete’s running to be studied. Maybe his heel is not striking correctly, or she’s walking flat-footed. No more guesswork. Now, they know.

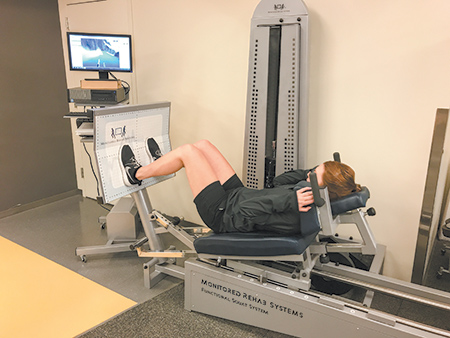

And over here is the machine that simulates skiing on a downhill course. The athlete hops on, and suddenly, he’s in Vail.

“The kid thinks he’s playing a game,” Boersma said. “What we’re doing is rehab. They’re trying to get high scores; we’re sitting there monitoring how much weight we can expose them to. They forget what we’re doing. That’s for this generation. They want games.”

Moving along, here is the HydroWorx pool, a 10-foot-by-14-foot creation that has jets for resistance, a movable treadmill on the floor that can go up and down, and underwater cameras, so every move can be monitored. Cross-country runners, five at a time, have hopped into water for a jog. Waist-deep, chest-deep, whatever.

“You can drop it 7-1/2 feet, so even Isaac Haas could float in this,” Boersma said, referring to the men’s basketball team’s 7-2 center.

They have insoles and shirts available here with sensors and GPS capabilities, to be worn at practices or games. “Afterward, they sync them and it’ll tell them how long they ran, how many bursts they had. How many times did they jump? How many times did they stop?” Boersma said.

OK. But why?

If the medical staff can see how every muscle works, spot weaknesses or imbalances, come up with plans to correct this or strengthen that, little problems can be fixed before they turn into big problems.

“The person that has the imbalance doesn’t even know it. If we can address it, science has shown they have a lower risk of injury,” Boersma said. “One of the biggest things that has changed from not even that long ago, maybe 10 years ago, is that we try to address things before they happen. Now there’s all these tools out there.

“One of the things I stress to my staff—this place cannot be the place of the misery. Meaning, we’re only treating the sick and the injured. If you would have walked in in the early 2000s, it would be a lot of tables, some therapy. Now the things you’re seeing are the pools, the treadmills. This is the place we teach student-athletes, ‘This is how you take care of yourself.’”

Same for the weightlifting room.

“They haven’t lost scope with getting bigger, faster, stronger—the whole idea of what strength coaches used to do. They’re still doing a lot of that. They’re just doing it smarter now.”

And it seems to be working, said Boersma, a Purdue grad who has been in this line of work for two decades, and at his alma mater since 2012.

“Kids handle physical stress better. And when they do get injured, it seems like they’re not out as long. You’re never going to get away from the really significant ligament injuries. We can’t train those ligaments. I wish we could train the ACL to be the strongest ligament in the body. If I figured that out, we wouldn’t be having this interview here; we’d be in a mansion someplace.”

And game day? New stuff there, too.

“On the horizon in the Big Ten, they’re going to start having a replay that you can go back and look at just injuries,” Boersma said. “It’s an iPad, and you can look at an injury right there in the sidelines. You can go back to the mechanics of what happened.”

But some things are still the same.

“If you go with the nuts-and-bolts piece of game-day injury evaluation, it comes down to whether the student-athlete feels they can go or not. That hasn’t changed at all. With the exception of head injuries. We don’t leave that in the hands of student-athletes.”

Indeed, as big a change as the technology for college medical folks is the hyper-concern about concussions, especially in football.

“Now you err on the side of caution, always. Always,” Boersma said. “There’s some frustration from coaches, just because they remember how it used to be. We’re just not messing around with it anymore.

“The players used to fight us on it. I can remember other players telling me after a game, ‘I had to tell whoever what the play was because he didn’t know what the signals were.’ Now I don’t get that as much. I get more a teammate coming to me saying, ‘Hey, Johnny’s not feeling well, and on that last series, I had to tell him every which way to go.’ Teammates wouldn’t have told me that a lot before. I think they realize it is serious.”

So this is today in the training of college athletics. Modern do-dads, modern theories on how to prevent injuries and, if that fails, how to heal them. At a school famed for its engineering, Purdue is never far from the next big thing.

“As long as people keep trying to figure out ways to keep our kids training faster, training longer, training safer, we’ll continue to have technology going through the roof,” Boersma said. “What’s next? I don’t know. I’m keeping in tight with our smart people across campus.

“I hope it’s not a robot that replaces athletic trainers.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.