Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowSometimes a gift is more work than it’s worth.

That could be the case for the Great American Songbook Foundation, which recently received the 107-acre Asherwood estate from Bren Simon.

The gift from Mel Simon’s widow is valued at more than $30 million, making it an extraordinary gift for any organization—but it comes at a cost. The foundation now has to maintain the property, which includes paying a nine-person staff as well as utilities, insurance and possibly property taxes.

The estate, which runs along the west side of Ditch Road between West 96th and 106th streets, includes a 70,000-square-foot main house, 7,000-square-foot clubhouse, 6,000-square-foot guesthouse, three maintenance buildings that total 20,000 square feet, and a golf course.

“Most organizations are not well-equipped to deal with asset donations like that,” said Bryan Orander, president of Indianapolis-based Charitable Advisors. “Their business is not events; it’s not managing real estate; it’s not really anything associated with this lavish property… . It’s a potentially tough situation.”

The foundation, which is affiliated with the Center for the Performing Arts in Carmel, declined to share the exact cost of estate maintenance, but it could be hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not millions, annually.

The foundation’s 2015 budget was less than $1 million, according to the latest federal tax filing.

McDermott

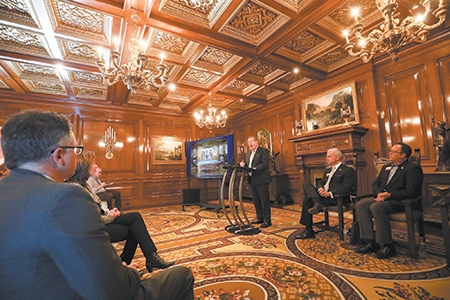

McDermottCenter for the Performing Arts CEO Jeff McDermott said the group’s leaders considered the costs when weighing whether to accept the gift, and determined they could handle the expenses.

“It’s a whole lot more work than a gift of cash or securities,” said Dave Sternberg, a faculty member at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy and a partner with Loring Sternberg and Associates. “You now become the owner of the property, and now you have maintenance costs. Or do you turn around and sell it? And then you have the responsibility to sell it.”

For now, the foundation is still deciding what to do with the massive property, where covenants could restrict development.

“We certainly have not explored anything specific,” McDermott said. “There’s obviously a lot of great potential here.”

Years of possibilities

This is not the first time the Simons have tried to donate the estate, whose main house has 36 rooms, including seven bedrooms and 24 full or half baths.

In 2008, Bren and Mel Simon worked with the Indiana University Foundation to give the land to the university, potentially to house a think tank.

Had it materialized, the gift would have likely included cash to support ongoing expenses. At that time, observers pegged the estate’s value at $50 million and annual upkeep at $1 million.

Discussions with the Songbook Foundation and the Center for the Performing Arts seem to have started a few years ago as Bren Simon again toyed with the idea of donating the estate. Mel Simon died in 2009.

McDermott said foundation officials—he was on the board then—toured the property at that time. He suspects other not-for-profits did as well.

“It was just very, very preliminary and nothing came of it,” he said.

In the meantime, local homebuilder Paul Estridge Jr. announced in November 2016 that he planned to buy the property to build 100 custom homes and convert the Simon mansion into an inn.

But just months later, conversations about donating the land started again and Songbook Foundation leaders met with Simon to negotiate a deal.

Last September, Estridge revealed that his plans were uncertain because neighborhood covenant restrictions would limit development.

With that proposal falling through, Simon sped up her talks with the foundation. Board members and the foundation’s management team became involved in the analysis of whether to accept the gift.

Such an evaluation would need to include an inspection of the property and any structures on it, an environmental review and a market valuation, said Phil Purcell, adjunct faculty member at the IU Maurer School of Law and Lilly Family School of Philanthropy.

Orander said not-for-profits need to consider the long-term impact of significant land or building gifts because they can do more harm than good if the expenses become too high.

“You see situations like that where nonprofits will be tempted by the perceived value without taking into account everything that can happen,” he said.

“You see situations like that where nonprofits will be tempted by the perceived value without taking into account everything that can happen,” he said.

The boards for both the foundation and the Center for the Performing Arts voted at a Dec. 14 meeting to accept the gift. The donation was announced Jan. 4.

To manage the property, the foundation took over the salaries of nine full-time staff members already working at the estate in maintenance, housekeeping, grounds-keeping, landscaping and security.

“The longer that the property sits on the market, the more those carrying costs go up,” Purcell said.

Charities can sometimes negotiate with the donor to receive ongoing support for those costs, he said, but it’s unknown whether Simon’s gift to the foundation included anything beyond the property itself.

“I don’t think it’d be appropriate to talk about that,” McDermott said when asked whether the gift included a cash component.

The foundation might also be on the hook for property taxes. Land owned by a not-for-profit is tax-exempt only when used for the organization’s mission.

According to Hamilton County records, the estate paid more than $266,000 in property taxes in 2017.

Sell or stay?

McDermott said one of the gift’s attractions was the possibilities it presented because it came with no restrictions.

“It really is kind of a game-changing gift,” he said.

Ideas for the property, including a free-standing Great American Songbook Hall of Fame Museum, are flooding in, and not much of anything has been ruled out. That includes the possibility of selling part or all of the land.

Other than a museum, McDermott declined to discuss possible considerations, saying the foundation is establishing an oversight committee made up of board members who will help make the decisions.

“I don’t think we were prepared to say exactly what we’ll do,” McDermott said. “It’s just way too premature.”

But fundraising consultants say charities usually have a plan for property before announcing a gift, and groups usually end up selling the land to generate cash for operations, programs or an endowment.

That doesn’t mean selling is easy. Often, donated property is land an owner has struggled to sell, and Asherwood seems to fall into that category. It had been on the market since 2014 with an asking price of $25 million.

There are examples of not-for-profits using the donated property, though.

The Indianapolis Museum of Art, now known as Newfields, acquired the Columbus home and gardens of the late Cummins Inc. Chairman J. Irwin Miller and his wife in 2008.

Known as the Miller House, the museum still owns and maintains the property. The gift from the Miller family and the Irwin-Sweeney-Miller Foundation included $5 million toward an $8 million endowment for maintenance.

With the estimated high cost of maintaining Asherwood—and the secrecy about whether the gift came with financial support—fundraising experts suspect at least part of the property will be sold.

“Your gut instinct would be that they’re going to sell it,” Purcell said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.