Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now Thirty-seven years later, what the umpire from Danville remembers about the longest professional baseball game ever played is the cold.

Thirty-seven years later, what the umpire from Danville remembers about the longest professional baseball game ever played is the cold.

Spring always brings back that night to Tony Maners. It was April 18, 1981, and the Pawtucket Red Sox were hosting the Rochester Red Wings in the Triple-A International League. A future Hall of Famer named Cal Ripken Jr. was playing third base for Rochester. A future Hall of Famer named Wade Boggs was at third for Pawtucket. And an Indiana native named Tony Maners was working first base. They were all about to help midwife history.

Over a recent breakfast, the memories flowed for Maners.

“The wind was blowing from center field toward home plate. They said it was 34 degrees outside with a wind chill factor of 8 above zero. Everything that was in my trunk was on me. Double layer, triple layer. I had snowmobile gloves on and actually gave them up after 16 innings. I happened to meet my crew chief out there in the outfield and I saw his hands turning purple and I said, ‘Here, you take them for the next 16 innings. If we go another 16, you can give them back to me and it’ll be my turn.’”

How was he to know they’d all still be out there 16 innings later, and by then, his little joke would be about as funny as frostbite?

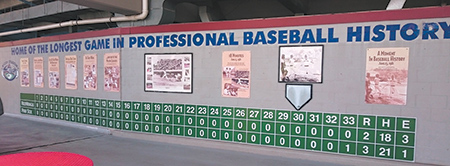

The record book will show that Pawtucket and Rochester played 32 innings that night and toward dawn, finally gave up at 4:09 a.m. with the score tied 2-2. By then, it was Easter morning.

“We technically had our sunrise service coming out of the ballpark,” Maners said. “The sun was starting to come up.”

Two months later …

The game would not resume until the Red Wings were back in Pawtucket on June 23. By then, the story had gone global, and the media poured in to see how it would end. “It was like a World Series,” Maners said. “The place was packed. There were reporters from Japan and England.

“It went 18 minutes.”

Dave Koza’s RBI single quickly won it for Pawtucket 3-2 in the bottom of the 33rd inning—after 882 pitches, 60 strikeouts, 219 official at-bats, 53 runners left on base, eight hours and 25 minutes of playing time, and 67 days on the calendar.

Ripken was 2-for-13, Boggs 4-for-12. Dallas Williams, who would eventually play for the Indianapolis Indians, was 0-for-13, which remains a record. Twenty-five players who appeared in that game would end up in the major leagues.

And Maners would have a conversation-starter for the rest of his life.

“It got my name into Cooperstown. But every coach, every player, every person I’ve ever told, I say I’m only one blade of grass on the ballfield.”

He has spent his life hustling around the sports landscape. Umpire school led Maners as a young man to Florida. He worked minor-league ball up to the Triple-A level and some major-league exhibitions—Braves Manager Bobby Cox once complimenting him on his consistent strike zone.

His dream of making the majors full time never came true, so he shifted to college and worked in the SEC and ACC, advancing to a gaggle of College World Series assignments. “When the Lord closes a door, He opens a door somewhere else. When He closed that major-league door, He opened up the college door.”

There were also sports camps, officiating basketball and volleyball. He worked the shot clock for 17 years for the Orlando Magic, once annoying Chicago Bulls Coach Phil Jackson, who wagged his finger at him and said, “I’m watching you.” After the Magic games, Maners helped with the cleanup crew.

Now he’s back home again in Indiana, in his 60s, mentoring and evaluating umpires. He’s also a scorekeeper for Danville basketball. And the lasting images of a frigid night long ago in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, are never far away.

How it started …

“Zero to zero until the top of the seventh. Both teams had 55-gallon drums in their dugouts and the bullpens, and they were burning fire. I snuck over a couple of times just to warm up a bit and then got back to my spot. Everything seemed to be normal.

“But I noticed five fly balls that should have been home runs [held up by the wind]. It was tied 1-1, then nobody scored until the top of the 21st.”

That’s when Rochester took a 2-1 lead in the top of the inning, but a Boggs single tied it for Pawtucket in the bottom. A report from the game mentions that even Boggs’ teammates groaned at his hit.

“We went the whole night without going to the bathroom. We got candy bars at 2:30 in the morning. The home-plate guy didn’t want his and he gave it to me. So I had two candy bars at 2:30 in the morning.

“There weren’t that many hit balls later in the game because the players were so tired. They were just swinging and missing. You knew you did not want to have a close play which would decide something of this magnitude.”

How it ended, in confusion about a curfew …

“I read in the rulebook, 12:50 in the morning. But my interpretation manual, which supersedes the rulebook for the International League, said curfew imposed by law [and there wasn’t one in Pawtucket]. We went in the locker room long enough to open up the book and found the page I had known in my head and took it out to show [the managers]. And they showed their page, the bottom of page 32—I remember because we went 32 innings that night. Their book said 12:50, and ours said curfew imposed by law. We took both rulebooks page by page and they all matched, except for half the page down, that one paragraph was changed. I don’t know why; I don’t know how. So we kept going, because we knew that’s what the president had given to us as umpires.”

Tony Maners has spent most of his career calling minor league and college baseball games. Today, he helps evaluate and mentor umpires. (IBJ photo/Eric Learned)

Tony Maners has spent most of his career calling minor league and college baseball games. Today, he helps evaluate and mentor umpires. (IBJ photo/Eric Learned)Finally, someone woke up International League President Harold Cooper just after 3 a.m. Horrified, he called Crew Chief Jack Lietz to the phone during the bottom of the 31st inning. The game went on into the 32nd while they discussed what to do. The decision was to stop at the end of the 32nd if there was still a tie.

Maners: “We were tired and frustrated. We didn’t have a winner. Plus, Jack told us we were all getting fired because we had kept going; that’s what the president of the league said to him. But by Monday, this became a historic ballgame, and now everybody is calling the league president to find out stories. Monday, he took us out to dinner. So we went from being fired to having dinner on the chief.”

One thing Maners has kept from that night: “The interpretation manual. I’ve got proof I knew what I was talking about.”

He also owns the memory that still shines through a lifetime of games.

“I’m very blessed. I tell people when I get to Heaven for those old-timers games, I’m never going to miss a pitch.”

And it won’t be as cold as Pawtucket.•

__________

Lopresti is a lifelong resident of Richmond and a graduate of Ball State University. He was a columnist for USA Today and Gannett newspapers for 31 years; he covered 34 Final Fours, 30 Super Bowls, 32 World Series and 16 Olympics. His column appears weekly. He can be reached at [email protected].

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.