Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIndiana’s war on the opioid epidemic is a classic good news, bad news story.

The good: Prescriptions for opioid painkillers in Indiana fell about 10 percent in the first eight months of this year. The bad: Indiana still has one of the highest rates in the country.

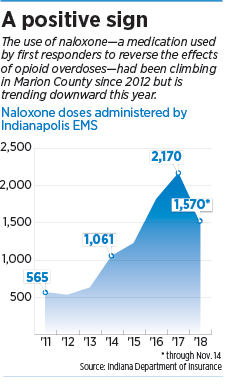

The good: Doses of naloxone administered by first responders in Marion County for drug overdoses fell 22 percent in first 10 months of this year. The bad: That’s still more than triple the amount for all of 2012.

The good: Visits to emergency rooms for drug overdoses across the state are starting to dip. The bad: Some emergency physicians say they are not noticing and are still overwhelmed.

More than two years after the state set up a Commission to Combat Drug Abuse, the report card is showing some encouraging signs, but still has far to go.

“We know we’re on the right path,” said Jim McClelland, Indiana’s executive director for drug prevention, treatment and enforcement—or “drug czar”—a position created by Gov. Eric Holcomb in January 2017, shortly after the state created the commission.

McClelland

McClelland McClelland added: “When you start to see signs of progress, that’s when we really need to redouble our efforts. We need to pick up the pace wherever we can and end this crisis.”

McClelland added: “When you start to see signs of progress, that’s when we really need to redouble our efforts. We need to pick up the pace wherever we can and end this crisis.”

The crisis, however, has been years in the making, and the job of wrestling it to the ground has grown into a massive task. No one is yet predicting when the state will be able to declare victory.

Last month, a new study prepared by Indiana University’s Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health at IUPUI warned that Indiana is “still very much in the grips of the opioid crisis.” It said the epidemic had evolved in recent years from one mostly involving addictive painkillers into dangerous street drugs.

“What began largely as a prescription opioid problem [has] surged into the street, where heroin and ‘fake’ pills resembling prescription drugs are now often laced with deadly amounts of illegally produced fentanyl,” the report said.

The number of overdose fatalities from opioid drugs mushroomed more than twentyfold from 2000 (36 deaths) to 2016 (785 deaths), according to figures from the Indiana State Department of Health.

Marion County led the state with the highest number of deaths due to drug overdose as well as non-fatal emergency department visits.

Newhouse

NewhouseFull-court press

In response, coalitions are popping up around Indiana to try to address the crisis in a comprehensive way, and tear down silos among various agencies and organizations.

The Indiana Commission to Combat Drug Abuse, formed by the Legislature in 2016, is one example. It is made up of more than a dozen state officials in law enforcement, social services, public health, education, corrections, the Legislature and other groups.

Together, the commission members share a wide array of information, such as naloxone data, best practices for treating substance-abuse disorders, and grant-funding sources.

And in recent months, other groups have sprung up to try to connect an even wider group of people and organizations.

Bill Corley, retired CEO of Community Health Network, formed a not-for-profit called INSTEP to encourage collaboration among key players. Last month, the group held its first working session, which brought together 37 health-provider and community organizations to discuss how to build a coalition focusing on the prevention, treatment and recovery of substance-abuse disorders in central Indiana.

Corley said he was influenced by a book—“Dreamland,” by Sam Quinones—that looks at the history of the opioid crisis, primarily in Appalachia—a region that includes Ohio, Kentucky, West Virginia and other states hit hard by the drug epidemic.

“The only way you’re going to turn the tide of this addiction in America is by getting the whole community involved,” Corley said.

And a big part, he said, is educating the community that opioid addiction is a chronic disease, and shouldn’t be viewed as a stigma or character defect. What it needs, perhaps most of all, is places to go for treatment and care.

More treatment options

Indeed, Indiana has been adding treatment centers at a steady clip. In the past few years, it has opened 19 treatment centers and has invested millions of dollars in inpatient beds, abuse counseling and other treatments. In the next year or so, the state plans to open nine more, McClelland said.

Indeed, Indiana has been adding treatment centers at a steady clip. In the past few years, it has opened 19 treatment centers and has invested millions of dollars in inpatient beds, abuse counseling and other treatments. In the next year or so, the state plans to open nine more, McClelland said.

Meanwhile, hospitals and health systems have been rolling out new recovery techniques. Indiana University Health has been using “recovery coaching”—employees who are in active recovery from addiction help coach patients who are struggling with substance-abuse disorders.

Last year at Methodist Hospital, 69 percent of the 284 patients admitted for substance-abuse disorder completed a six-month program.

In September, IU Health expanded the program, using video hookups between Indianapolis and other IU Health hospitals in rural parts of the state with limited on-site resources.

“We know this program will make a difference,” said Mike Haley, senior vice president for behavioral health at IU Health. “Instead of a clinician who’s never known what they’ve gone through, the patients will bond with the coaches quickly and stay with the treatment longer.”

At Eskenazi Health, a safety-net hospital that serves mostly underinsured patients, physicians and nurses are forming partnerships with police, community groups and social service agencies to get patients help once they are discharged.

“We are trying to find any and every way we can to lessen the crisis,” said Dr. Charles Miramonti, an emergency physician at Eskenazi and chief of parent Marion County Health and Hospital Corp.’s emergency medical service system.

He said he is encouraged by a few signs: Ambulance runs for opioid overdoses, where the treatment drug naloxone is administered, have dropped almost every month this year, compared with last year. If that pace holds through December, it will mark the first annual decrease since 2012.

“We’re not out of the woods yet,” he cautioned.

Research efforts

Meanwhile, researchers at Indiana University Health are gearing up for the next big push in a comprehensive, $50 million research effort to tackle the epidemic.

The university recently announced it had funded 15 new projects in the program, known as the “Responding to the Addictions Crisis Grand Challenge.” The projects include studying the impact of opioid addictions on the labor market, examining the stigma of addictions, and looking at how to create a more effective version of naloxone.

The university recently announced it had funded 15 new projects in the program, known as the “Responding to the Addictions Crisis Grand Challenge.” The projects include studying the impact of opioid addictions on the labor market, examining the stigma of addictions, and looking at how to create a more effective version of naloxone.

The projects are on top of 15 others announced last year, when IU kicked off the ambitious program.

Robin Newhouse, dean of the IU Nursing School in Indianapolis and principal investigator of the opioid project, said the sweeping approach was the best way to tackle the epidemic.

The goal is to reduce deaths from addiction and ease the burden of drug addiction on Indiana communities.

“The disease has affected the people of Indiana, their families, the children, as well as the economy,” she said. “We have to work together. There are many people and organizations in the community fighting at the same time. It’s an attack that has got to be comprehensive.”

Perhaps most heartening, she said, is that many people are no longer indifferent or unaware of the epidemic. In a recent statewide survey, 94 percent of respondents said they were either very or somewhat aware of the opioid crisis.

Likewise, about 70 percent said they were either very or somewhat sympathetic to patients who suffer from addiction.

Leaders in the fight say they are pushing to continue making a dent, little by little, over time.

When asked to compare the war on opioids to a baseball game, McClelland declined to say how many at-bats Indiana can muster, or even what inning it was, or how soon the state could declare victory.

“But I’ll tell you one thing,” he said. “There’s going to be no seventh-inning stretch. We’ve got to keep running as hard as we can. And we will, I assure you.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.