Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now As you read this, new transit stations are being set in place along the Red Line route. After years of waiting, excitement is building over the arrival of Indy’s first “fixed guideway” transit in more than 60 years. Certainly, I am looking forward to riding the Red Line regularly to get to work and leisure haunts. What I’m most excited about, though, is something bigger. Key advances in the history of our city have come along with the advent of passenger rail (or fixed guideway) transportation.

As you read this, new transit stations are being set in place along the Red Line route. After years of waiting, excitement is building over the arrival of Indy’s first “fixed guideway” transit in more than 60 years. Certainly, I am looking forward to riding the Red Line regularly to get to work and leisure haunts. What I’m most excited about, though, is something bigger. Key advances in the history of our city have come along with the advent of passenger rail (or fixed guideway) transportation.

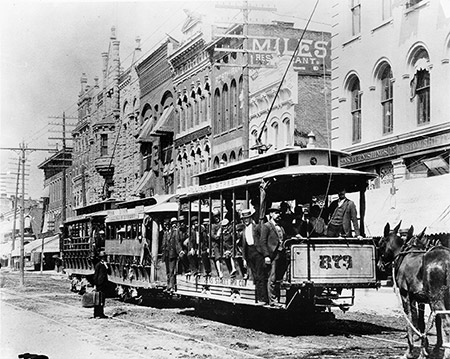

For the first 20 years of its existence, despite being the state’s capital, Indy had fewer than 3,000 people. Just a decade later, with the arrival of rail, the population tripled. The next decade saw the establishment of the nation’s first Union Station and the population more than double. In a city that was never perceived likely to grow larger than its original Mile Square, electrified streetcars by the late 19th century made possible the establishment of neighborhoods in “far reaching” areas like Bates-Hendricks, Fletcher Place, Cottage Home, Ransom Place and the Old Northside. In the first three decades of the 20th century, “interurbans” shared the street rail lines, connecting to most major cities within a 120-mile radius, creating what became the largest interurban system in the country.

Beyond the occasional rail that peeks through the pavement, the signature of the streetcar can be seen throughout the city. Every line stretching out from the center of the city played a role in establishing some of our most beloved neighborhoods, institutions, workplaces and landmarks.

Along the new Red Line alone, a route that shares its alignment with several former streetcar lines, can be found the University of Indianapolis, Garfield Park, the Statehouse and Methodist Hospital. Broad Ripple and Fountain Square essentially owe their existence to streetcars. The same goes for the fine-grained, walkable commercial nodes that dot College Avenue at former streetcar stops. An extra lane in College Avenue was originally a fixed guideway that ran all the way to Kokomo and was the last streetcar to be shut down, in 1953.

The automobile era that has dominated since then has never managed to match the kind of population growth and prosperity that coincided with the heyday of fixed guideway transit in Indianapolis. While the land area of the city has grown more than 11-fold, containing 8,400 lane-miles of road (the United States is 3,000 miles across), the population has only about doubled. Also, what these broad numbers mask is that the core of our city—the old city limits technically referred to as the Compact Context Area, or CCA—has lost half its population.

To put a finer point on it, recall how outrageously motivated nearly every major city in the United States was to attract the 50,000 people Amazon’s HQ2 promised to bring? Our CCA is more than 75,000 people smaller than it was at the height of streetcars in the 1920s.

Like people, young cities must focus on physical growth. In adolescence, they must secure their identity. Again, much like people, for a mature city like Indianapolis, physical growth is a worry, even an indication of decline. The priority must instead be on vitality—building the strength and resilience that supports longevity and well-being.

This is why I’m enthusiastic about the Red Line and the whole system of rapid transit it introduces. Where once streetcars created possibilities by reaching beyond downtown, rapid transit will today allow us to more easily reach our middle neighborhoods with their inherent density and walkability.

We must use the Red Line to focus on bringing a critical mass of people back to the neighborhoods where we already have the most invested in infrastructure and housing. We must do this, not because it is trendy but because walkable urban places are simultaneously the most efficient use of our limited resources and our best chance to create a vital and socially resilient city.•

__________

Gallagher is a principal and urban designer with Ratio and a professor-in-practice of urban design at Ball State University. Send correspondence to [email protected].

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.