Subscriber Benefit

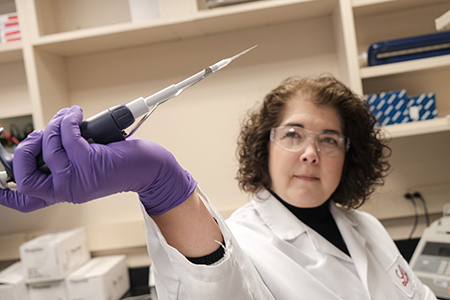

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn a small room in Eli Lilly and Co.’s cancer laboratories, biologist Michelle Swearingen gets down to work. She pulls on a pair of purple lab gloves and clips a vial of blood to a machine, hoping to see whether the blood has a healthy number of immune cells—the soldiers that defend the body from tumors and other invaders.

Swearingen hits a button and the machine, called a flow cytometer, sucks the blood out of the vial in a narrow stream, thinner than a human hair. The machine hums and lasers bounce off the blood, which is mixed with fluorescent dyes to help highlight the contents. On a nearby computer screen, a graph pops up, showing hundreds of tiny dots.

“So, immediately I can see I have plenty of immune cells here,” Swearingen says in a pleased tone, ticking off the scientific names of different cells. “I’ve got my monocytes, I’ve got my T-cells, I’ve got my neutrophils.”

“So, immediately I can see I have plenty of immune cells here,” Swearingen says in a pleased tone, ticking off the scientific names of different cells. “I’ve got my monocytes, I’ve got my T-cells, I’ve got my neutrophils.”

The next step: Mix the blood with different drugs to see if they can get more active and robust, as part of a major effort to develop ways to use the body’s immune system to attack cancer cells. Around Lilly labs, cancer researchers go through these steps countless times a week, hoping to gain fresh insights into new treatments for cancer, a disease that has challenged researchers for decades.

Lilly, long a leader in diabetes and neuroscience drugs, is pushing hard and spending record sums to turbocharge its oncology business, potentially a huge growth area. In January, Lilly paid $8 billion to buy Loxo Oncology, a Connecticut-based startup that is developing cancer-treating medicines based on tumors’ genetic traits. Last May, Lilly paid $1.6 billion for ARMO BioSciences Inc., a publicly traded California company that is a rising star in the burgeoning field of immuno-oncology.

Last year, cancer drugs accounted for about 20 percent of Lilly’s revenue, or $4.3 billion. But the Indianapolis-based company has bigger dreams.

White

White“We do see this as a significant growth area for the business,” said Lilly Oncology President Anne White. “And so we’ve been investing, because we believe that, if you look at some of the forecasts, about 30% of the revenue growth in the pharma industry will come from oncology, and probably nine of the top 20 products in 2024 will be oncology products.”

Lilly has been talking for years about becoming a major player in oncology. In 2008, then-CEO and Chairman John Lechleiter predicted that Lilly would become a “true oncology powerhouse” following its acquisition of ImClone, maker of Erbitux, a drug for head, neck and colorectal cancer.

But it has remained a fairly small player, ranking ninth in oncology pharmaceuticals. The industry leader, Roche, racked up $27.8 billion in cancer drug sales, six times what Lilly brought in.

And even as Lilly pushes hard into oncology, other companies are announcing huge deals of their own. In January, Bristol-Myers Squibb announced a blockbuster, $73 billion deal to buy rival Celgene Corp., which would team up two of the industry’s top players in cancer. A month earlier, GlaxoSmithKline PLC unveiled plans to spend $5 billion to buy Tesaro Inc., which is developing drugs for breast and ovarian cancer.

Growing market

Lilly’s current portfolio of cancer drugs targets such diseases as lung, colorectal, head and neck, gastric, pancreatic, breast and ovarian cancers. (IBJ photo/Eric Learned)

Lilly’s current portfolio of cancer drugs targets such diseases as lung, colorectal, head and neck, gastric, pancreatic, breast and ovarian cancers. (IBJ photo/Eric Learned)The need for new cancer treatments is immense, though U.S. cancer death rates have declined. The rate peaked at 215 deaths per 100,000 people in 1991; by 2014, it had fallen 25 percent, to 161 per 100,000 people, according to the American Cancer Society. Much of that was due to reductions in smoking, as well as improvements in early detection and treatment.

All the companies are aiming to make a huge impact in bringing the rate down further. Each year, 14 million people around the world receive a cancer diagnosis, and many die within a few years. Last year, nearly 10 million people died from cancer, according to the World Health Organization, making it the second-leading cause of death, behind only heart disease.

The worldwide market for cancer drugs is estimated at $133 billion, and is expected to reach $200 billion by 2023, according to the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science, a research and consulting firm based in Durham, North Carolina. Drug companies are pouring huge amounts of money into cancer research, in part because cancer drugs command a premium price and the demand for better treatments is intense.

“Everybody is flocking to oncology,” said John LaMattina, senior partner at the Boston biotech firm PureTech Health and former head of Pfizer’s research and development. “There’s tremendous competition. But if you can develop a better treatment, you will be rewarded greatly.”

LaMattina

LaMattinaSome of Lilly’s top prospects in oncology in recent years have run into big setbacks. In January, the company said tests for Lartruvo, its cancer drug for soft-tissue sarcoma, didn’t meet its main goal of showing improved survival in patients with advanced or metastatic disease, despite promising data from an early-stage study. In response, federal regulators in the United States and Europe said no new patients should start treatment with Lartruvo.

Another Lilly cancer drug, Portrazza, which treats an aggressive form of lung cancer, has rung up only modest sales since its launch four years ago, due to better treatments available since then.

In fact, Lilly’s top-selling cancer drug is Alimta, for lung cancer. It has been on the market since 2004, and last year rang up $2.1 billion in sales.

It’s the company's one home-run performer in oncology, even as Lilly tries to develop new drugs. The company’s other cancer drugs include Cyramza (lung, gastric and colorectal cancer), Erbitux (colorectal, head and neck cancer) and Verzenio (metastatic breast cancer).

In the meantime, it has more than a dozen experimental drugs in its pipeline to treat an assortment of cancers, from pancreatic to liver.

In the meantime, it has more than a dozen experimental drugs in its pipeline to treat an assortment of cancers, from pancreatic to liver.

Some analysts look at Lilly’s cancer lineup, its recent acquisitions and its internal pipeline, and say the company is moving in the right direction.

“I think they’ve got a very solid franchise,” said Les Funtleyder, a health care analyst for E Squared, a hedge fund based in New York City. “A couple of more drugs and they can be a serious player.”

CEO David Ricks, a longtime Lilly executive who moved into the top job in 2017, is eager to make his mark. He has made it clear to employees and investors that he wants to pursue acquisitions to supplement the company’s internal R&D.

Daunting challenges

But the challenges facing Lilly—and other pharmaceutical companies trying to find the next big cancer treatment—are daunting.

Cancer is one of the toughest diseases to understand. In fact, it’s not just one disease, but perhaps dozens or hundreds. What they all have in common is uncontrolled growth and spread of abnormal cells. The four most common types are lung, colorectal, breast and prostate.

Cancer has stymied researchers for decades, even as companies have poured tens of billions of dollars into research. Cancer is often genetically unstable, and one person’s cancer could dramatically change in just a few years, making it difficult to treat consistently.

Garraway

GarrawayThe success rate for new cancer drugs is just 5.1 percent, the lowest of any disease area, according to BIO, a huge biotech trade association. That means 95 out of every 100 cancer drugs that go into clinical testing are scrapped along the way.

But cancer varies widely in research advancement. For some types of cancer, researchers in the last two decades have been able to better understand their biology and design a medicine to target them effectively.

“But oftentimes, that’s not the case,” said Dr. Levi Garraway, Lilly’s senior vice president for oncology research and development. “Sometimes, the discovery just gets bogged down, because we don’t already know how to make a small molecule or antibody against this kind of target.”

Lilly is trying to speed up the pace through head-turning acquisitions. When it bought Loxo, a 6-year-old drug-development firm, it picked up the company’s pipeline of potentially game-changing cancer drugs, including one being studied for multiple tumor types that recently was fast-tracked by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The FDA granted it “breakthrough therapy” status, which positions it for possible launch in 2020.

Some analysts see the drug, called Loxo-292, as a breakthrough for patients with a certain type of mutation known as RET. Louise Chen, an analyst with Cantor Fitzgerald, wrote to clients on April 14 that she expects Lilly to report positive mid-stage clinical results later this year and the drug to be approved next year, making it the first of its kind on the market.

Some analysts see the drug, called Loxo-292, as a breakthrough for patients with a certain type of mutation known as RET. Louise Chen, an analyst with Cantor Fitzgerald, wrote to clients on April 14 that she expects Lilly to report positive mid-stage clinical results later this year and the drug to be approved next year, making it the first of its kind on the market.

“Physicians we spoke with think that Loxo-292 could be transformative for patients with RET fusions or mutations,” she wrote. She added that the drug could potentially have other uses in the future, “which would increase the target patient population.”

Lilly’s top research executive, Dr. Dan Skovronsky, told an investor conference in March that the drug’s biggest opportunity is in lung cancer, but could also be used in thyroid cancer and possibly a wide variety of tumors.

“And then we’re really also very excited about the Loxo pipeline,” Skovronsky said. “The team at Loxo has just done a phenomenal job at identifying targets where there’s a high unmet medical need, a clear biologic rationale based on genomic alterations” in tumors that can be treated with drugs.

‘Shots on goal’

Lilly’s oncology R&D strategy is to identify the most promising drugs, and pour lots of resources into them. The bar is high, Garraway said, and many drugs just don’t cut it and are flushed out as soon as possible if they can’t prove they will outperform others already on the market. But drugs that look promising get lots of resources, because Lilly says it wants to tee up as many high-performing cancer drugs as possible.

“Part of what it takes to be successful in oncology is the willingness to take enough shots on goal,” Garraway said. “We’re not satisfied with the number of shots on goal that we have. On the other hand, we also feel like it’s better to take shots where we have conviction than it is to sort of be doing ‘spray and pray.’”

Lilly won’t say how much money it is spending to develop oncology drugs, but clearly it is keeping busy. Scientists in the company’s cancer laboratories, just south of downtown, are examining numerous approaches to attack tumors with a variety of drugs and testing procedures.

In one corner of a laboratory, researcher Diane Bodenmiller examines under a microscope live cancer cells harvested from kidneys, breasts and bones to better understand their shape and movements. Swearingen, the biologist, prepares a batch of blood samples for inspection under the laser machine.

A major goal in this lab, according to Senior Research Scientist Beverly Falcon: Go through test after test to find ways to help the body fight cancer, using its own immune system. It’s a long process, filled with trial and error, but one that could ultimately lead to better treatments.

That involves analyzing immune cells in countless experiments—looking for ways to make them more powerful, more energetic and ready to attack cancer cells with precision and overwhelming power.

“You want to see if you can get them more happy, more activated,” she said, “so they can go fight.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.