Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA Fishers man is facing a tangle of legal issues related to accusations that he was involved in the nationwide sale of more than $230 million in questionable financial products.

The depth of the situation came to light after Robyn Dale “Rob” Whitlow, 51, filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy protection late last month, declaring personal assets of $45,305, balanced against liabilities of just more than $2 million.

According to court records from that case, most of Whitlow’s liabilities are related to potential penalties and settlements in five civil and regulatory actions involving Whitlow and his now-defunct Indianapolis company, American Alternative Investments LLC. The largest of those potential liabilities is connected to a South Carolina case in which a court-appointed receiver is attempting to recoup more than $850,000 in sales commissions.

In all five of the cases, Whitlow and AAI—and in some cases additional defendants—are accused of selling to individual investors financial products that have drawn scrutiny from securities regulators and/or prosecutors. Those products were from Resolute Capital Partners, 1 Global Capital and Future Income Payments LLC.

The five cases include civil actions filed by securities regulators in both Pennsylvania and Washington state.

In the Washington case—which names Whitlow, AAI and three individual codefendants—regulators say that Whitlow, AAI and another AAI executive sold at least $180.6 million in securities affiliated with Resolute Capital Partners, and at least $53 million in 1 Global Capital securities, to investors across the U.S.

Whitlow’s legal entanglements also include civil suits filed by investors in Florida and California. The plaintiffs say Whitlow, AAI and other defendants persuaded them to invest in now-defunct Future Income Payments LLC, which both lawsuits describe as a Ponzi scheme. Those lawsuits, and another pending civil suit in South Carolina, are now stayed as a result of Whitlow’s bankruptcy filing. The regulatory cases are unaffected by the bankruptcy.

To be clear, Whitlow—who did not respond to attempts by IBJ to contact him for this story—is not accused of creating any of these financial products. Rather, each of the cases alleges that Whitlow was involved in selling the products to individuals across the country, often by using networks of unregistered agents in violation of securities laws.

Nor is Whitlow the only individual facing allegations related to selling the products. Instead, each case involves a web of sales activity, only some of which involves Whitlow and AAI.

Who is Whitlow?

Despite the array of legal actions and numerous business entities connected to him, Whitlow seems to have kept a low profile in his home state.

He did not return calls and emails from IBJ. His bankruptcy attorney, Dave Krebs of Hester Baker Krebs LLC, declined to comment.

Krebs told IBJ he had advised Whitlow not to discuss pending matters.

Attorneys representing Whitlow in the other cases did not respond to IBJ queries.

In Indiana, the Office of Secretary of State’s securities division handles enforcement of the state’s securities laws and licensing of securities brokers. A representative for the office said the agency has not ordered any administrative action against either Whitlow or AAI. The representative declined to say whether the agency is aware of Whitlow.

“As a standard practice, we do not comment on potential or ongoing investigations,” the office’s representative said via email.

Likewise, local attorneys who specialize in securities law told IBJ they were unfamiliar with Whitlow’s name until a reporter brought him to their attention.

Whitlow’s bankruptcy filing reveals that his business involvements have been broader than just AAI. He has been connected to more than a dozen business entities within the past four years, either as an owner, managing executive or some other key role.

Six of them, including AAI, were still in operation at the time of his bankruptcy filing. Another eight entities ceased operation between October 2018 and December of last year. Storefront packing/shipping/copy shops on the north side of Indianapolis serve as the official address for eight of those entities, including AAI.

But there’s no direct mention of any of these companies on Whitlow’s profile page at Revenue River, the Colorado-based sales and marketing agency where Whitlow now works as vice president of global sales. A Revenue River employee said Whitlow works for the company remotely. Whitlow’s LinkedIn page indicates he has been with the company since October 2021.

The Revenue River profile page describes Whitlow as a serial entrepreneur who launched his first business at age 11 and hired his first employee at age 12, “selling lawn mowing service door to door, and hiring neighborhood kids to perform the work.” Whitlow went on to work for his father’s insurance agency before going out on his own and starting a new company “that grew to over $200 million in five years with over 1,400 reps.” The profile does not name that business.

Whitlow’s LinkedIn page says he graduated from a Christian high school in 1988 with a 3.98 grade point average. The page does not include any mention of where or whether he attended college.

The LinkedIn page also lacks much specificity about Whitlow’s career history. For instance, he lists himself as the founder and CEO of AAI, but describes his role there in vague terms, using phrases like “developed and implemented business plan and strategy,” “identified and developed new opportunities” and “pro-actively participated in all facets of the company.”

Troublesome financial products

Although they hadn’t heard of Whitlow, two local attorneys say they’re quite familiar with the financial products Whitlow is accused of selling.

Indianapolis attorney Mark Maddox, who specializes in securities law but is not involved in any of the Whitlow cases, said Future Income Payments, Resolute Capital Partners and 1 Global are well known as problematic entities within the securities world.

Maddox, founder of the law firm Maddox Hargett and Caruso P.C., has represented investors who filed lawsuits against all three.

He said it’s not often that a defendant faces accusations related to multiple unrelated schemes, as is the case with AAI and Whitlow. “What really amazed me about this guy was his involvement in so many toxic investments,” Maddox said after reviewing the cases.

Also unusual, he said, is the high dollar value that the Washington regulators attach to Whitlow and AAI’s sales activities related to two of those troublesome products: Resolute Capital Partners and 1 Global Capital securities. “Those are pretty rare numbers for just [one] selling group to do nationally in just one or two products.”

Carmel attorney Keith Griffin of Griffin Law Firm LLC said he’s also familiar with the securities Whitlow is accused of selling. “The products have been problematic throughout the country,” he said.

Griffin characterized the products as the type of non-mainstream investment that typically gets pitched to individuals who are neither wealthy nor financially sophisticated—perhaps a retiree for whom an investment of $50,000 or $100,000 represents most or all of his or her personal assets. “That’s who’s getting victimized in these kinds of cases,” Griffin said.

In September, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission issued a cease-and-desist order against Resolute Capital Partners Ltd. LLC, Homebound Resources LLC and the two men from Nevada and Texas who ran the companies, saying the parties used “material misrepresentations and omissions” to sell more than $250 million worth of unregistered investments in oil and gas wells.

Florida-based 1 Global filed for bankruptcy protection in July 2018. A month later, the SEC charged the company and its former CEO, Carl Ruderman, alleging the defendants had “fraudulently raised more than $287 million” over the past four years using a network that included barred brokers.

Future Income Payment’s owner, Scott Kohn, was arrested in California in 2019 and has been charged with more than a dozen fraud and conspiracy charges in a federal criminal case pending in South Carolina.

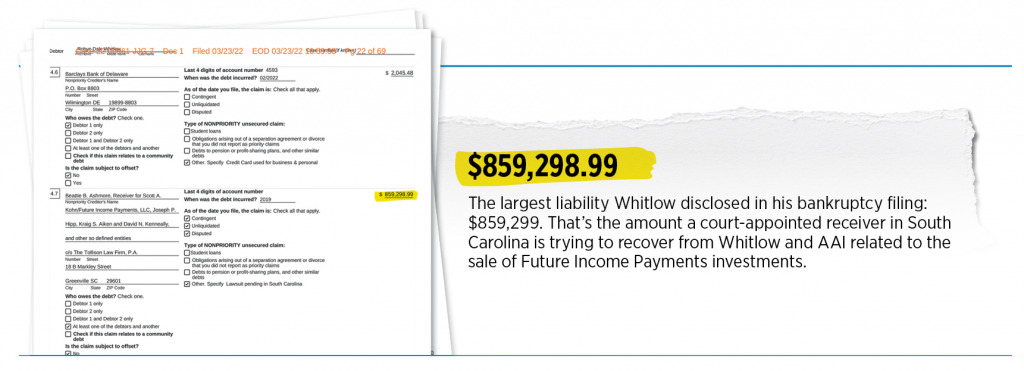

In a related federal case also in South Carolina, a court-appointed receiver filed a civil suit against Whitlow and AAI in June 2020 as part of a larger effort to identify and recoup assets from Kohn, Future Income Payments and the other defendants in that criminal case. The receivership lawsuit alleges that Whitlow and AAI received commissions of at least $859,299 “associated with the sale of products that were part of a criminal Ponzi scheme orchestrated and effectuated by Kohn, FIP and others.”

State regulators’ cases against Whitlow

According to an online database maintained by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, neither Whitlow nor AAI have ever been licensed to sell securities.

That point is at the heart of pending regulatory cases in Washington state and Pennsylvania.

In September, Washington’s Department of Financial Institutions filed a legal action against Whitlow, AAI, and another AAI executive as well as two men from California and Nevada who are described as AAI sales agents.

Between 1993 and 2015, the second AAI executive was registered to sell securities. However, he is not currently registered, FINRA records show. The Indianapolis man did not return a message left on what IBJ believes is his cell phone.

Whitlow previously held an insurance license in Indiana, according to the Indiana Department of Insurance’s online database. Whitlow became licensed to sell life, accident and health insurance in 2003, but that license expired in August 2021. AAI was issued a license to deal in life, accident and health insurance in August 2016, and that license expired two years later.

An insurance license isn’t the proper credential for selling investment products.

The Washington state regulatory action accuses Whitlow and AAI of using a nationwide network of unregistered sales agents, including so-called “bad actors,” to sell unregistered securities from 1 Global, Resolute Capital Partners “and other unregistered offerings that have been the subject of enforcement actions by the SEC and state securities regulators.”

Under federal securities law, a securities issuer who uses a bad actor—someone who has had a securities-related criminal conviction or other disqualifying event—must register its financial offering in the states in which it is conducting the offering.

Washington regulators are seeking a cease-and-desist order against Whitlow, AAI, the other executive and the two AAI sales agents. The regulators are also seeking to impose a $110,000 fine and $21,868 in court costs and fees for which AAI and the two executives would be jointly and severally liable.

In the Pennsylvania case, which was filed in November, state securities regulators say Whitlow and AAI recruited at least two people to sell 1 Global securities totaling at least $1.8 million to at least 22 Pennsylvania residents in 2017 and 2018, generating at least $74,339 in compensation for Whitlow and AAI.

The 1 Global securities were not registered, Pennsylvania authorities allege, nor was AAI registered to sell securities in the state. The regulators also allege that Whitlow and AAI failed to disclose material information to investors, including 1 Global’s operating history, financial condition, the identity and background of its corporate officers and the risks associated with the investment. By the time Pennsylvania regulators had filed the action, 1 Global had already defaulted on payments to investors.

Pennsylvania authorities are seeking to bar Whitlow and AAI from selling securities in the state, and to impose an assessment of up to $100,000 for each violation of state securities law. The case is pending.

Alan Rosca, a securities attorney who practices with the law firm of Rosca Scarlato LLC in suburban Cleveland, Ohio, described a type of “symbiosis” between disreputable financial products and unlicensed brokers. The creators of those financial products need agents to sell the products, but licensed and reputable agents aren’t interested—so the creators turn to agents who aren’t licensed and thus can’t sell legitimate financial products.

Though there are of course many licensed insurance brokers who play by the rules, Rosca said, a fair number of people who sell disreputable financial products also hold insurance licenses. There are a few reasons why, he said. Insurance brokers typically understand financial products and they have sales skills.

Also, the insurance industry is not as tightly regulated as the securities industry, Rosca said. “An insurance license is a lot easier to get than a securities license.”

Potential investors, though, may see any type of licensure as a sign of credibility.

The lawsuits filed by investors

The investor lawsuits that Whitlow is facing in California and Florida concern investments that the plaintiffs made in now-defunct Future Income Payments. That’s the California-based entity whose owner, Scott Kohn, is facing more than a dozen fraud and conspiracy charges in a federal criminal case pending in South Carolina.

Future Income Payments held itself out as a purchaser of individuals’ pensions, offering a lump-sum payout to pensioners who needed immediate cash. In return, the pensioners would agree to pay monthly payments to Future Income Payments. On the other side of the equation, Future Income Payments recruited investors to purchase what it called “structured cash flows” that were based on the pensioners’ monthly payments.

In Kohn’s indictment, prosecutors allege that the deals with pensioners were actually “usurious loans,” though Future Income Payments portrayed the deals as pension purchases. Prosecutors also accuse Kohn and his codefendants of misrepresenting the deals to investors.

As securities regulators in multiple states began banning Future Income Payments from doing business within their borders, and as the pensioners began to default on their payments, prosecutors allege, Future Income Payments became a Ponzi scheme that diverted funding from new investors into payments to earlier investors.

Future Income Payments ceased operations in the spring of 2018. Kohn was indicted the following year.

In both the California and Florida investor suits, the plaintiffs say they were persuaded to invest in Future Income Payments after hearing sales pitches that omitted key facts about the company.

The Florida case was filed in November 2018 in circuit court in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The suit was filed by individual plaintiffs—three of whom represent financial trusts—against Whitlow and AAI, as well as a Broward County, Florida, man and two Florida-based companies with which that man worked. The suit describes an arrangement in which the Florida man approached the plaintiffs and induced them to invest in Future Income Payments via Whitlow’s company, AAI.

In the suit, the plaintiffs say the defendants took “negligent, deceptive and fraudulent acts” to persuade the plaintiffs to invest in “a Ponzi scheme masqueraded as a legitimate structured cash flow account from the now defunct Future Income Payments, LLC.”

Each of the plaintiffs say they invested between $50,000 and $390,000 with Future Income Payments between February 2016 and March 2017. At the time they made the investments, the plaintiffs allege, the defendants were aware that Future Income Payments was under investigation by state regulators. “Defendants chose to ignore these warning signs and took advantage of Plaintiffs solely to sell them commission-rich product that were funding a Ponzi scheme,” the suit says.

The lawsuit includes an undated letter sent to one of the financial trusts from Whitlow, who identifies himself as CEO of AAI Global. The letter thanks the trust for purchasing a structured cash flows account through AAI, describing the product as a “customized income stream” that would provide “consistent and predictable income.”

But the plaintiffs say in their complaint that they stopped receiving payments in early 2018 and ended up losing more than half of their initial investments.

The other pending lawsuit, filed by California investor Benedict St. Onge, tells a similar story. St. Onge filed his California complaint in August in Orange County Superior Court against Whitlow, AAI and another AAI executive, among others. The other defendants include the same Florida man and one of the same Florida companies named in the Miami-Dade County suit, along with five California individuals described as partners and employees of that Florida company.

St. Onge’s suit alleges that he was looking for a safe investment that could generate income to help pay off his mortgage. In 2015, one of the California defendants recommended that St. Onge invest in Future Income Payments, and St. Onge opened an account with AAI for the purpose of investing $188,300 in the product.

The lawsuit filing includes a copy of an undated letter to St. Onge, thanking him for his purchase of a structured cash flows account through AAI.

The defendants failed to mention numerous salient facts about Future Income Payments, St. Onge alleges, including that the entity was operating as a Ponzi scheme by using income from newer investors to make payments to earlier investors.

St. Onge alleges that his monthly payouts from the investment ceased arriving in the spring of 2018, and that he lost $148,961 of his original investment.

From big commissions to bankruptcy

Legal documents suggest that Whitlow stood to gain through the commissions that he and his co-defendants earned by selling the various financial products.

The cease-and-desist order filed last year by Washington state securities regulators alleges that AAI earned commissions of between 3.75% and 12% on the 1 Global Capital and resolute Capital Partners securities that it sold. Whitlow, AAI and the other executive kept about a third of those commissions, with the remainder split between the agent who actually sold the product and those who had recruited that agent into the sales network.

And the South Carolina case, which concerns Future Income Payments, alleges that Whitlow and AAI received at least $859,299 in direct or indirect commissions from the sale of FIP products—products which the lawsuit describes as being “part of a criminal Ponzi scheme orchestrated and effectuated by Kohn, FIP [Future Income Payments] and others.”

The defendants sold these products by providing buyers with information that was “false and misleading through marketing material and high-pressure seminar style information sessions,” the suit alleges. “Defendants either made these representations with knowledge of their falsity or with reckless disregard for the truth of the statements.”

The court-appointed receiver who filed the complaint against Whitlow and AAI is asking that the defendants return the money they received from the sale of the Future Income Payments products.

Rosca, the Cleveland-area securities attorney, said high commissions like the ones described in the cases are a hallmark of disreputable financial products. One reason why, he said, is that the promoters need to offer an enticing reason for agents to sell those products. “They typically pay far higher commissions than what legitimate companies pay,” he said.

But now that Whitlow has filed for bankruptcy protection, it may not be possible for investors or regulators to collect any of the money they’re seeking from him and AAI.

On April 4, the South Carolina attorneys that had been representing AAI in the receivership case asked the court for permission to withdraw as its counsel “because this business [AAI] has gone out of operation, is reported to have no assets, and is reported to have no insurance which would be available to stand for any judgment brought in this action.”

Those attorneys, who had also been representing Whitlow, also told the court that “Mr. Whitlow has filed for bankruptcy and communicated he no longer desires our services.”

Whitlow’s bankruptcy filing means the civil suits against him will be put on hold. The plaintiffs could choose to file adversary cases, which are essentially civil suits within the larger bankruptcy case.

But Maddox said that’s unlikely, especially given that Whitlow has filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy protection.

Chapter 7 is known as liquidation bankruptcy, in which the debtor’s assets can be sold and sales proceeds distributed among creditors. It’s different from Chapter 13 bankruptcy protection, in which the debtor intends to repay his or her debts over time.

“Most people don’t chase adversary proceedings into Chapter 7 because of the lack of collectability,” Maddox said.

Maddox also noted that, after a Ponzi scheme or fraudulent financial operation implodes, the people who sold such products often end up in bankruptcy.

“It’s not uncommon for guys like this to go broke,” he said, “filing Chapter 7 bankruptcies a few years after the gravy train ends.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.