Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowLike the rest of state government, Indiana’s top courts have become overwhelmingly Republican over the past 25 years.

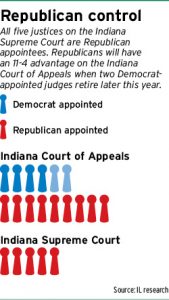

Today, all five justices on the Indiana Supreme Court are Republican appointees.

And when two more Democrat-appointed judges on the Indiana Court of Appeals retire later this year, Republicans will have an 11-4 advantage on that court.

Despite the heavy Republican tilt, many court watchers on both sides of the political spectrum agree that the state’s high courts haven’t seen the kind of political polarization apparent in many other states.

They say that’s because of the state’s merit selection process, which uses a special nominating commission that tends to produce a pool of centrist judicial candidates for the governor to choose from and appoint.

“Flaming moderates” is how former Indiana Supreme Court Justice Frank Sullivan Jr., a Democrat appointee, likes to describe the current composition of the state’s high court and Indiana Court of Appeals, despite their overwhelmingly Republican composition.

But moderation is not a term used to describe courts in many other states around the country, especially those in which high court judges are elected or the governor has more say in who is appointed.

A report by the Center for Public Integrity and USA Today last year found that eight states over the past decade have changed their judicial selection process to allow for more politically conservative judges to take the bench.

In Iowa, that resulted in the state’s supreme court flipping its position on abortion in just four years, according to the center.

In 2018, Iowa’s high court ruled that the state constitution provided a right to abortion that was “fundamental to the notion of liberty.” In 2022, a reconstituted court found that no such right existed.

By contrast, liberals gained a majority on the Wisconsin Supreme Court in the 2023 election, resulting in power struggles over everything from abortion to legislative district maps.

Merit selection

In Indiana, the merit selection process for the state’s top judges was created in 1970 and has kept the composition of the state’s high courts more moderate, many say.

The Judicial Nominating Commission is in charge of vetting applicants for the Indiana Supreme Court and the Indiana Court of Appeals. It conducts public interviews of the applicants and then submits the top three candidates for each vacancy to the governor, who makes the final selection.

The commission is composed of seven members: three attorneys, three non-lawyers and the state’s chief justice. The three non-lawyers are appointed by the governor and the three lawyers are elected by members of the bar.

Indiana is one of 12 states that uses merit selection to fill positions on the bench. The most common method in the U.S. is having judges elected by popular vote. At least 20 states elect their state supreme court justices.

That distinction is what allows Indiana courts to remain more moderate no matter which political party controls the governor’s office, court watchers say.

“The seven members of the nominating commission work together to try to achieve some kind of consensus and just the nature of consensus … is to move people towards the center, towards compromise, towards moderation,” said Sullivan, the former state supreme court justice. “And that is, I think, the great genius of our process. Even if a particular member of the nominating commission might favor an extremist of one kind or another. That’s just not going to survive the crucial role of negotiation of the seven members of the nominating commission.”

For the past 20 years, the GOP has controlled the governor’s office, allowing Republicans to fill all the vacancies created as appointees named by Democratic Govs. Frank O’Bannon, Joe Kernan and Evan Bayh in the 1990s and early 2000s retire.

Appellate judges Patricia Riley and Terry Crone are planning on retiring this year. Riley was appointed by Bayh in 1994 and Crone was appointed by Kernan in 2004.

But even with their departure, that won’t change the centrist nature of the court, Sullivan said.

“I don’t think that if we continue to have Republican governors it will make any difference. And if we change in 2025, from Republican to Democratic governor, I don’t think it will make any difference,” Sullivan said. “The men and women who have been appointed to the court, since merit selection, have been distinguished by their nonpartisanship. And their fidelity to deciding cases based on the law and the proven facts without any reference to extraneous factors.”

Former Indiana Supreme Court Chief Justice Randall Shepard, a Republican appointee, said that merit selection works well in selecting the best possible candidates to serve Hoosiers.

“I think the answer is that Indiana has protected itself,” Shepard said. “We’ve managed to adopt a system which has meant that it doesn’t turn out to be noticeably partisan.”

Jim Bopp Jr., a staunch social conservative known nationally for crafting model anti-abortion legislation, said he wouldn’t call Indiana’s state courts “moderate” because he doesn’t like the word. But he criticized the nominating commission for selecting “elites” as judicial appointees.

“The politics is underground,” Bopp said. “I’m not for elites running our country, okay … but that’s what merit selection does, in the name of the lie, which is, it’s what only matters are their qualifications, not their philosophy.”

Some point to the Indiana high court’s ruling on abortion as one example of the justices showing more moderation than the Republican-dominated Legislature.

While the court ruled last year that the Legislature’s near-total abortion ban doesn’t violate the state’s constitution, a majority of the court did not consider the ruling to be the final word on the legality of Indiana’s abortion restrictions and appeared to invite future challenges.

“By saying (the ban) is not unconstitutional in its entirety in all circumstances, we do not say the opposite either — that every single part of the law can be applied consistent with our Constitution in every conceivable set of circumstances,” the decision said.

The court found that while the General Assembly retains broad legislative discretion for determining the extent to prohibit abortions, the state’s constitution provides some protection of abortion rights.

Whether the state’s high court will grant new exemptions to the abortion ban is expected to become more clear if it hears an expected appeal of a recent Indiana Court of Appeals decision. Last month, the appellate court ruled that the state’s abortion restrictions should not apply to women who have a sincere religious objection to continuing a pregnancy.

In another culture-war issue, the state supreme court declined to hear a case involving the custody of a transgender girl, letting stand a lower court decision that the state was right to take the child away from her devout Christian parents.

The parents argued that they should be able to raise the child based on the child’s sex at birth. The state said the parents lost custody not because of their views but because of the medical need to address the child’s eating disorder.

Attorney William Groth, who advocates for labor unions, civil rights and voting access, said he doesn’t see political views seeping into the justices’ decisions but has noticed some factions forming on the state’s high court.

“I don’t think these judges by and large make decisions based on politics, and I think they try real hard to get each decision correct,” said Groth, who is with the law firm of Bowman & Vlink LLC.

But he said the state’s high court does seem to be coalescing into two factions on certain cases, with Chief Justice Loretta Rush and Justice Christopher Goff opposing some majority rulings by Justices Mark Massa, Geoffrey Slaughter and Derek Molter.

In the disciplinary case against Republican Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita, both Rush and Goff disagreed with the public reprimand imposed by the court’s majority and argued that the punishment should have been harsher.

Rush and Goff also dissented against the majority ruling last month to effectively keep John Rust from running for U.S. Senate on the Republican primary ballot on May 7.

At issue was the constitutionality of a law that requires Republican candidates to have voted in the last two Republican primaries or receive the blessing of their county party chair to run as a Republican.

Rust didn’t meet either of those requirements and the court ruled 3-2 that they were constitutional under the “rights of association” for political parties. But Rush and Goff disagreed in a dissenting opinion, noting that the fundamental principle of representative democracy is that the people should be able to choose whom they please to govern them.

As an advocate for ballot access, Groth wrote an amicus brief in the Rust case on behalf of Common Cause Indiana and the Indiana League of Women Voters. He sided with Goff, whose dissenting opinion in the case argued that “primaries are not meant to be opportunities for party leaders to crown their favored candidates.”

Here to stay?

Some academics see Indiana’s merit selection process for state judges as something worth protecting, and the chair of the Indiana Senate Judiciary Committee said she’s heard of no interest in changing it.

Sen. Liz Brown, the committee chair and a Fort Wayne Republican, said judicial officials tell her it’s a process that works.

Bopp, however, would like to see the process changed because believes the best way to select state judges is through partisan elections.

Joel Schumm, a clinical professor of law and director of experiential learning at Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law, pointed to Wisconsin as an example of what can happen when a state supreme court becomes particularly polarized through an election.

In 2023, liberals won a majority on the Wisconsin Supreme Court for the first time in 15 years and immediately sought to weaken the powers of the conservative chief justice, setting the stage for power struggles over abortion and the drawing of legislative districts.

“They have elections and then you don’t have stability or stable precedent,” Schumm said of Wisconsin, noting that key decisions can be quickly overturned when the balance of power shifts.

“If you didn’t like the first decision, maybe you’re happy that it changed,” Schumm said. “But in the law, we generally value and appreciate stability, consistency, predictability, and you lose those things if you have people running political sort of platforms and then getting on the bench and deciding cases that way.”

At the county level, the merit selection process is running into some opposition.

While most county judges in Indiana are elected, judges in Allen, Lake, Marion and St. Joseph counties are appointed through a selection process.

Calls for change are coming in Marion County, where a man recently convicted of reckless homicide in the death of Indianapolis police officer Breann Leath received a sentence widely criticized by public safety officers and elected officeholders as too lenient.

Marion County Superior Court Judge Mark Stoner on April 4 sentenced Elliahs Dorsey to just more than five years in prison for Leath’s death. However, Dorsey also was sentenced to 25 years in prison for the attempted murder of his ex-girlfriend with 15 more years on mental health probation.

As a result of that sentence, state Rep. Mitch Gore said he will seek changes to Marion County’s system for selecting judges, possibly allowing voters to petition for a recall of appointed judges. The judges already face a retention vote every six years.

Elsewhere in the state, the selection system has been criticized for preventing the most diverse counties, which also happen to be the most Democratic, from voting on judges.

Early this year, Hammond Mayor Tom McDermott and Democratic state lawmaker Lonnie Randolph joined a former Lake County judge in challenging the process, alleging in a lawsuit that it violated the Voting Rights Act. The U.S. District Court for Northern District of Indiana upheld the state’s judicial selection system but that decision has been appealed.

State Rep. Ed DeLaney was one of few Democrats who supported the selection system when it was instituted at the county level. Now he says he recognizes flaws with the system—it prevents voters in the most diverse of Indiana’s counties from selecting their own judges, for example—but he still sees it as the best compromise.

“I’ve tried to think as a lawyer and as a supporter of the system,” DeLaney said. “I do ask, ‘How is this working so far?’ It seems to be working.”•

__________

Indianapolis Business Journal reporter Taylor Wooten contributed to this story.

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.

The missing part of this is what Bopp alluded to, the politics of the selection process. The IBJ should do an article on which faction of the Indiana bar controls their three slots on the judicial nominating commission, for example.

Bopp’s criticism might be more valid if it wasn’t obvious he wanted to pack the court with ideologues like him.

To Bopp, you’d probably go after those elites by choosing someone like Indiana’s Sarah Pitlyk, who got a lifetime federal judgeship despite being laughably unqualified because she believed the “right” things according to Bopp.

Or maybe he’d prefer they choose someone like Aaron Freeman to be a Supreme Court justice. Can’t wait until Freeman rules that drivers have a constitutional right to run pedestrians over.

All attorneys know the state’s Pi attorneys tend to control the nominations and vote only for fellow PI attorneys. Even the public members tend to have connections with PI law firms.

Why do some Hoosiers act as if moderation in setting legal precedent is a bad thing?

As Joe B. points out, it’s only “bad” if one wants to use the courts to tilt things toward the extreme views of radical ideologues.