Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe Indianapolis Zoo’s shift to new leadership began with a brief conversation in Mike Crowther’s office in early 2014.

The longtime president and CEO of the Indianapolis Zoological Society—which operates the zoo—had called in one of his top deputies, Rob Shumaker, to ask him a couple of big questions.

“What are you thinking about for your future?” Shumaker recalled his boss asking him.

“And I said, ‘Well, I’m very happy here—I like being here. I don’t plan to leave.’”

Then came a bigger question: “Are you thinking about moving up into other roles?”

The truth was that Shumaker hadn’t thought about it. He had been focused for five years on establishing the zoo’s $26 million orangutan center, which was opening in May of that year. The task gave him little time—or desire—to ponder what might come next in his career. But the idea was intriguing.

After a moment’s pause, Shumaker told his boss he was open to taking on more responsibility and bigger roles in the conservation community—but not if it meant leaving Indianapolis.

While that was the end of the conversation for the time being, his response was exactly what Crowther had hoped to hear.

The then-61-year-old was looking for a successor—and he believed Shumaker was the right person for the job.

“That was where we kind of started,” Shumaker, told IBJ. “Nothing was guaranteed at that point, to be sure, but it planted the seed in my mind.”

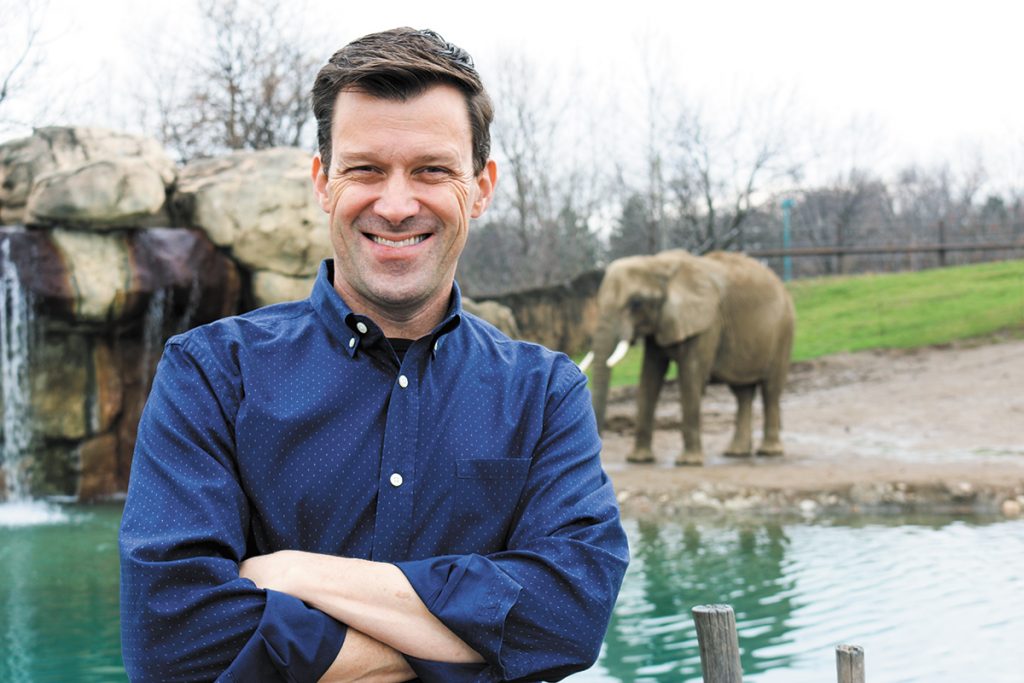

Shumaker, 55 and now president of the zoo, will take over as CEO for the retiring Crowther in early January.

In doing so, the Washington, D.C., native inherits a business operation that has been on a financial upswing for nearly two decades—all while investing tens of millions of dollars to create state-of-the-art exhibits and conservation programs in addition to growing visitor counts, memberships and charitable donations.

Since Crowther was hired in 2002, the zoo has seen a nearly 240% increase in annual revenue (which is expected to top $32 million in 2019) and a 700% increase in the value of its endowment fund (now $41.1 million).

In the past decade, its total assets have grown to $151 million, an increase of more than 27%.

Attendance is up, too—about 34% since his hiring—although many major U.S. zoos are experiencing similar increases.

Even so, industry experts say Crowther’s business acumen has helped make the Indianapolis Zoo one of the nation’s most mission-driven animal organizations, pushing other facilities to bring their own conservation efforts into focus.

Conservation focus

Among the zoo’s biggest successes during Crowther’s tenure was the creation of the Indianapolis Prize, which was first awarded in 2006 and has become one of the world’s most prestigious conservation awards.

The prize, with winnings of $250,000, is awarded biennially to a conservationist who has had a significant impact on animal biomes or species and has raised the profile of animal preservation.

In addition, the zoo is next year launching a global endangered species center.

And it has added several exhibits, including the orangutan facility, that are geared toward getting visitors interested in conservation.

“I think it would be fair to say [Rob Shumaker] has some big shoes to fill, but also I’m confident that he will do a great job of filling them,” said Kris Vehrs, executive director of the Maryland-based Association of Zoos & Aquariums, the zoo’s primary accrediting body.

Shumaker said he got the job because the zoo’s board of trustees is confident he will continue down Crowther’s path.

“I think it’s very fair for me to say we don’t have anything that’s broken, and we don’t have any problem areas,” Shumaker said. “All we have are opportunities.”

He said that while neither he nor the board wants to “redefine the Indianapolis Zoo,” it could stand to further distinguish itself from other zoos by using innovation to give visitors a more real connection to the animals—and by increasing the zoo’s already-deep focus on conservation.

“We certainly prioritize conservation a bit more than some colleagues—and a lot more than other colleagues—but I think that’s a natural evolution for zoos, and it’s not new,” he said. “The modern generation of zoos are conservation organizations, and that’s really what our focus is here in Indianapolis.”

That focus came with Crowther’s hiring, when he challenged the board at that time to take a different approach to its operations.

Crowther said he was interested in creating and “being a part of a new kind of conservation organization, which serves as a bridge between the people and resources of the developed world and the needs and opportunities of the natural world.”

“Beginning [then], we said we were not going to be a menagerie with a collection of animals that people come and look at,” he said. “We were going to be an institution that takes people through the process of engaging them in wild things in wild places, and enlightening them about challenges … then empowering them to take personal ownership of the situation.”

Today, the Indianapolis Zoo is involved with efforts to save Amur tigers, care for injured sloths, protect cheetahs, provide education about gorillas, and capture, breed and release scarlet macaws and the endangered great green macaw in Costa Rica. Other programs benefit elephants in Tanzania, parrots in Bolivia, orangutans in Sumatra, and coral reefs in the Caribbean.

Several tests

Jeffrey Harrison, chair of the zoo board, said Crowther formally pitched Shumaker as his potential replacement in late 2014, when the board began discussing succession plans—including the possibility of opening the position to both internal and external candidates.

Jeffrey Harrison, chair of the zoo board, said Crowther formally pitched Shumaker as his potential replacement in late 2014, when the board began discussing succession plans—including the possibility of opening the position to both internal and external candidates.

“As we began to look and compare skill sets [of potential hires], we realized that we had a significant talent in Rob Shumaker,” said Harrison, president and CEO of Indianapolis-based Citizens Energy Group.

He said Crowther believed Shumaker was the right fit for the job and would keep the focus on conservation and education, rather than reaping profits as he said some U.S. zoos do.

At the CEO’s urging, the board began testing Shumaker with more responsibility and authority, all while keeping a watchful eye on the national landscape for alternatives.

Shumaker participated in the Association of Zoos & Aquariums’ Executive Leadership Development Program in 2015, to hone his executive skills. The program focuses on teaching lower-level executives about effectively running facilities, prioritizing conservation and developing leadership skills.

His first dose of additional responsibility was overseeing the finance and human resources departments—areas in which he had little formal experience.

Shumaker had risen through the ranks at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Zoo in Washington, D.C., leading animal-related departments, rather than business operations. In eight years at the Great Ape Trust in Des Moines, Iowa, he prepared budgets but largely focused on research and conservation.

But Shumaker rose to the board’s challenge, and all the others thrown his way, Harrison said.

But Shumaker rose to the board’s challenge, and all the others thrown his way, Harrison said.

That included being appointed a zoo director in 2016. Directors oversee the executive team, organization-wide budgets and end-of-year reports.

Because Shumaker passed each test, the board suspended its informal national search in late 2017.

“We believed that we already had the best possible candidate, in Rob Shumaker,” Harrison said.

The right fit

The decision brought with it a new title—president, which was split from Crowther’s role—and even more responsibility, which Harrison said further proved Shumaker was the right pick.

“He’s got a great mind, in terms of running the operational aspects of the zoo,” Harrison said. “He also has a great passion for the organization and being a great community partner [with] the zoo.”

Robert Dale, a professor of psychology at Butler University, agreed that Shumaker is right for the post.

“I think he’s a brilliant, hardworking and extremely impressive individual,” said Dale, who studies elephant psychology and has spent 30 years on and off at the zoo for his research. “I don’t think they could have picked a better person to lead the zoo, frankly.”

Despite a difference in the men’s strengths—Shumaker’s deeper understanding of animals versus Crowther’s not-for-profit business experience—zoo operations are unlikely to change, Dale said.

“I think he’ll take over right where [Crowther] leaves off,” Dale said. “More importantly, I believe the zoo will become increasingly involved in conservation, which is what most of the best zoos are doing now.”

Shumaker said the board’s approach to readying him for the post was extremely effective, albeit somewhat unconventional in today’s business climate.

“I think what we did was really old-fashioned—allowing me to work as an apprentice” under Crowther, he said. “I think it was a tremendous benefit to be able to take the time and learn the intricacies of this organization.”

Crowther agreed.

“By the time he was ready to become CEO, he was absolutely ready to lead this organization, because he already knew everything about it as opposed to only knowing a little bit about it,” Crowther said.

Under Crowther, the Indianapolis Zoo has become an international leader in conservation and engaging visitors with animals in a compelling way, Vehrs said.

And Shumaker has been a major part of the conservation efforts—particularly related to primates—since his hiring as vice president of conservation and life sciences in 2010, she said.

Shumaker was integral in creating the Simon Skjodt International Orangutan Center, which he came to Indianapolis to help develop.

As part of the move, he brought with him several orangutans that had been harbored at The Great Ape Trust, giving them a new home in Indianapolis.

Shumaker also represented the zoo in Saudi Arabia in October as the organization signed an agreement with the International Union for Conservation of Nature to create a global endangered species center at the Indianapolis Zoo.

Pivotal point

The Global Center for Species Survival is scheduled to open next year and is backed by a $4 million grant from the Lilly Endowment. It is meant to be an integral conservation tool to preserve endangered species.

The Global Center for Species Survival is scheduled to open next year and is backed by a $4 million grant from the Lilly Endowment. It is meant to be an integral conservation tool to preserve endangered species.

“We know we’re at an absolutely pivotal point right now and shame on us if we don’t do something about it—we have to,” Shumaker said.

He said the center will allow Indianapolis to be a hub for important conversations about biome preservation and preventing the extinction of endangered animals—something he said will be a key focus for the zoo moving forward.

But Shumaker, like Crowther, will face the challenge of a number of competing interests at the zoo, Vehrs said, ranging from its role as a trusted source of information to serving as a local attraction, to leveraging its resources as a conservation organization.

His potential impact could include being known for “creating great, immersive naturalistic exhibits,” Vehrs said. “I think that’s certainly a possibility, along with other impactful conservation initiatives.”

He’ll also be the one to lead the species survival center, she added, likely sharing somewhat of a split legacy for the project with Crowther.

“Obviously, [Shumaker will] have his own ideas, and develop—over a hopefully very long career—his own legacy,” Vehrs said.

Shumaker said the zoo will develop a long-term strategy through comprehensive planning that will involve employee and community input.

“The one thing we need more than anything else when it comes to conservation is more voices supporting preservation of the natural world,” he said. “We need everybody involved at whatever level they can be.”

The zoo has also long wanted to expand by moving its parking lots. In September, it acquired 28 acres of land through an agreement with Indianapolis-based Ambrose Property Group, which owns the former GM stamping plant site across East Washington Street (and whose president, Aasif Bade, is on the zoo board). That land is now being used for overflow zoo parking, but the long-term plan might include moving most parking there.

Shumaker said a number of options are on the table. “This strategic plan is going to reveal [our goals] as we go forward, but it would not be genuine for me to tell you right now exactly what we’re going to do for the next 10 years because that would be nonsense,” he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.