Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowDavid Nolte, whose work could well lead to new, better and more effective ways to treat cancer, never set out to make a fortune. He never dreamed of becoming a captain of industry.

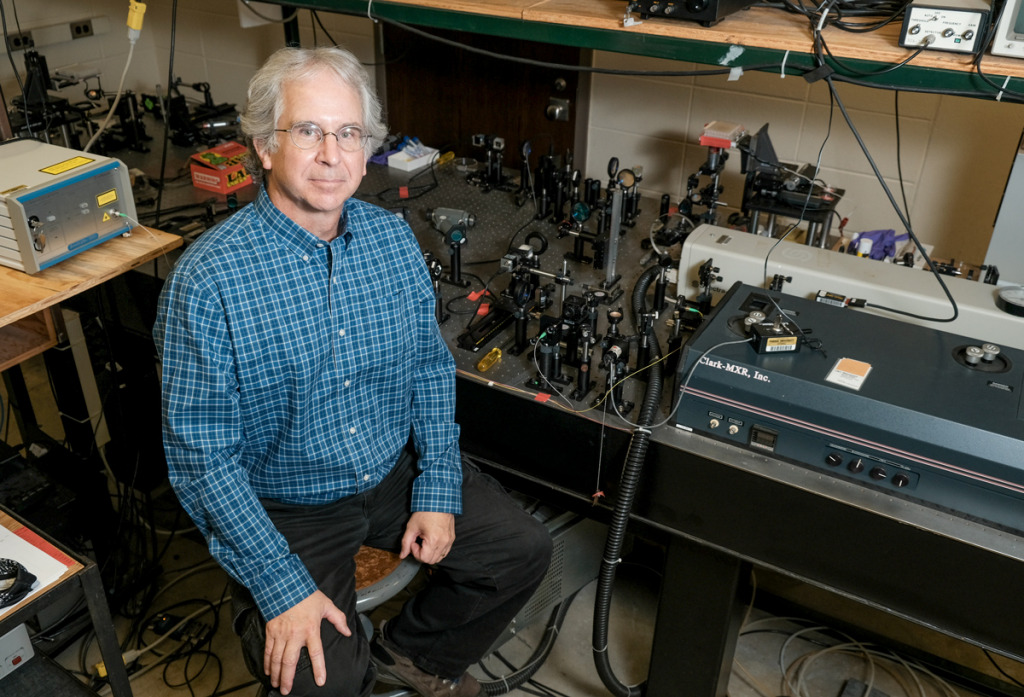

Good thing. Because the bespectacled 61-year-old Purdue University professor, whose silver hair falls casually to either side of a near-center part, has done neither.

Certainly not for lack of intellect. His peers say emphatically that Nolte is a world-class physicist. Nor for lack of ambition or a strong work ethic. Those same peers say he works countless hours at his craft.

Certainly not for lack of intellect. His peers say emphatically that Nolte is a world-class physicist. Nor for lack of ambition or a strong work ethic. Those same peers say he works countless hours at his craft.

But the patented inventions born from his brain—while they’ve given rise to companies—have not generated a great deal of money for him, his school or investors. At least not yet.

He has a potential home run right now—Animated Dynamics, a firm that recently raised $5.5 million in venture funding.

Still, for his part, Nolte, who earned his undergraduate degree in physics from Cornell University and his doctorate at the University of California at Berkley, isn’t overly concerned about the business world’s definition of success. He is fueled by different fires. He didn’t even ponder the full potential of the patented products he worked on until he was well down his career path.

In some ways, Nolte is typical of college professors and researchers: He spends his time studying, figuring and tinkering for long hours over subject matter he is obsessed by. The journey of discovery is the draw, rather than a pot of gold that might lie at the end of the rainbow.

But that is changing, as more and more of the work done by university researchers is being spun off into companies and commercial applications that they or the universities own or are a part of.

“Historically, professors used research as a tool to foster education as well as for problem solving and discovery,” said Peter Kissinger, a Purdue University analytical chemistry professor. “Many never think of taking their research commercial. They became professors because they love to teach and [for] the pursuit of knowledge. Seeking patents and starting a business is a whole different pursuit.”

It’s a pursuit many academics frowned upon, up until the 1980s or even 1990s.

“I remember clearly, in the ’70s, people—and many in academia—thought professors were tainted by commercial endeavors,” Kissinger said.

But for some, “a light goes on, and they realize their research could have a wider meaning and a big impact—a positive one—on the broader world,” said Kissinger, whose own research has given rise to Bioanalytical Systems, a contract research firm that sells its services to pharmaceutical, medical-device and biotechnology companies around the world. The company had 2019 revenue of $43.6 million.

“When it dawns on you that your research can actually make people’s lives better—now or in the relatively near future—that’s a big moment,” he said.

Early patents

That moment for Nolte came while working as a postdoctoral researcher at AT&T Bell Laboratories, a world-class tech lab in New Jersey.

That moment for Nolte came while working as a postdoctoral researcher at AT&T Bell Laboratories, a world-class tech lab in New Jersey.

From 1998 to 1999, Nolte worked on solid-state physics and semi-conductors at Bell Labs, where he learned about the process of filing patents and how the results of his research could lead to patented inventions.

“That was at a time when Bell Labs was the top research lab in the world. There was no other place on earth like it,” Nolte recalled.

Despite Bell’s emphasis on patenting research, AT&T didn’t always launch the technology into businesses or products. Instead, the company tended to sell or trade the patents.

“AT&T didn’t care about the technology. They just wanted to either leverage or package them as bundles and sell them off,” Nolte said.

At Bell Labs, Nolte worked with laser physics. “We invented … the most sensitive holographic film ever,” he said.

Nolte never even knew the value of the patents he worked on.

“I got a dollar for my AT&T patent” for holographic film, he said with a laugh. “I have no clue what they ever did with that patent.”

After joining Purdue as a professor in 1989, Nolte filed a few more patents based on his research.

“Even at Purdue, through the ’90s, there wasn’t much encouragement for faculty to launch startups,” Nolte said.

“The patents we filed were often with a company,” he said. “We would have non-exclusive rights to a patent. One of the patents was done with IBM; others were with small companies in California.”

Power to the schools

A powerful seed for change was sown 20 years before it began to produce real fruit.

The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 gave colleges and universities rights to intellectual property generated from federal funding. Co-sponsored by then-Sens. Birch Bayh, D-Ind., and Bob Dole, R-Kan., the law was seen as a way to pull the United States out of the economic malaise of the 1970s.

Schools—in Indiana and nationally—already had some understanding about the marketing value of products born from their research. Studies at Indiana University gave rise to Crest toothpaste and the Drunkometer (now known as the Breathalyzer blood alcohol calculator). From research at Purdue came Orville Redenbacher popcorn, Stove Top Stuffing Mix, fiberglass and the bright-red LED lights in automobile brake lights and traffic signals.

But many of those discoveries were commercialized outside the university system.

The Bayh-Dole Act gave researchers and schools financial incentive to pursue commercialization of research internally. Still, many academics and academic institutions were hesitant to dive in.

But in the 2000s, a new generation of university presidents emerged.

When Martin Jischke became president at Purdue in 2000, he started pushing the school’s researchers toward the commercial realm. A few years later, Indiana University President Michael McRobbie followed suit in Bloomington.

Mitch Daniels, the former Republican Indiana governor, took the effort to a new level when he became Purdue president in 2013. That triggered intensified efforts to capitalize on research at IU, the University of Notre Dame and other state schools.

“If you run a university with a professor, you will … rarely break the mold,” Kissinger said. “If you bring in someone with new ideas—with deep government, business and think-tank experience—you just can’t find that very often. Mitch Daniels brought in good people and was a lot more aggressive about what we can do.”

Fueling the fire

In the mid 2000s, colleges started programs and organizations to spur the research-to-market revolution.

Operations like Purdue Foundry, Purdue Ventures, Innovate Indiana Fund and IU Ventures launched, as did the IDEA Center and Innovation Park at Notre Dame. The schools and their backers started angel networks and capital funds, with the express intent of commercializing the research of faculty and students.

IU and Purdue researchers now crank out dozens of patents each year—in some years, well over 100.

“The number of startups and inventions coming out of the schools in Indiana is almost dizzying,” said IU Ventures CEO Tony Armstrong.

“There has never been more activity and more potential. And there’s never been more excitement, attention or opportunities around the research coming out of the state’s universities than there is now. … And I think there’s a lot more to come.”

Schools’ policies differ on how money from patents and startups is distributed, but a typical model has the faculty inventor taking 35% directly and getting another 15% to invest in his or her lab for more research. Another 15% or so usually goes into the inventor’s academic department and 35% goes to the school.

All the recent successes don’t mean the task is not daunting. A college professor or researcher has much to learn before launching a company. Grasping business management and capital markets is just the start.

Nolte is better equipped than most, said Purdue Ventures Managing Director John Hanak.

“First of all, David is a world-renowned physicist. He’s great to work with and totally understood what we were doing with ideation, development and startup,” Hanak said. “David was inherently more savvy about business. If he would have put his mind to being a CEO of a company, he could have done it. Instead, he applied his gifts to research.”

That’s important, Hanak said, because many professors get in over their head trying to fill the CEO role. “I knew he would be a success because he realized his role would be as chief scientific and technical officer.”

‘Nothing but left turns’

Nolte’s journey from academia to filing patents to launching companies was a bit more circuitous than most.

“My whole career has been nothing but left turns,” Nolte said.

After a stint working on high-energy particle physics, “constituents-of-reality type of stuff,” Nolte said, he moved on to high-altitude cosmology.

He spent a year working on a sounding-rocket project. But the rocket, which was designed to take measurements and perform scientific experiments while in orbit, sank in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Japan without ever opening its nose cone.

“The nose-cone bolts failed to fire,” Nolte said. “The next day, I switched to solid-state physics.”

He then worked on semi-conductors, which opened the door to his work at Bell Labs. There, he got into laser physics, which led to the work with sensitive holographic film.

“We started to ask the question, ‘What can we do with this?’ Somewhere along the line, somebody suggested, ‘Why don’t we look at living tissue?’” he recalled. “The next thing you know, a couple years pass, and I’m doing biomedical research [at Purdue].

“Like I said, it’s been nothing but left turns. Now, almost everything I do is related to cancer. So, I’m a cancer researcher.”

Motion pictures

The company born from Nolte’s research, Animated Dynamics, was founded in 2011 and has raised $5.5 million in capital. The company is pioneering technology that animates the traditional view provided by a microscope. The startup has created camera-like hardware that allows it to view living tissue in motion.

Nolte gives much credit for the launch of Animated Dynamics to his business partner, John Turek, a Purdue professor of basic medical sciences and Animated Dynamics vice president.

The technology, Nolte said, is important in helping doctors tailor treatment to patients’ specific cancer.

“The technology picks up all the motion going on inside of cells and the cells themselves,” Nolte said. “We’re able to see how those motions are affected by an applied therapeutic.”

He explained that the biodynamic imaging is created by shining a light on living tissue. The reflection of light waves creates a three-dimensional image that shows the real-time movement of living cells and structures inside them. While this type of imaging can be helpful in a long list of applications, the company believes helping cancer patients is its best application.

Those familiar with Nolte’s work at Animated Dynamics say he’s on the brink of a big breakthrough. It’s not the first time.

More than 15 years ago, Nolte came up with a way to fill the pits of a compact disc (like the ones that play music) with antibodies that collect proteins out of blood serum. “So, instead of having 5 billion empty pits, you have 5 billion pits that are actually testing the constituents of blood,” Nolte said. The BioCD was born.

Nolte started a company with a group from Notre Dame around the technology he invented. Quadraspec was launched in 2004. Nolte, who became chief scientific officer, and his partner retained 50% of the company, and 50% went to a new management team.

“Quadraspec had a spectacular trajectory,” Nolte said with a chuckle, “all the way up until the market crash of 2008. … We were about to sign an international deal that would have actually brought in a large chunk of investment with a human diagnostics company out of Ireland.

“That’s what we were shooting for. The contract was finished. All that remained was the ceremony to put on the signatures. Then the stock market crashed and that was basically the end of that company.”

The company’s employee count was nearly halved—to 17—in one month. Shortly after, all the assets were sold and Nolte essentially exited.

Lessons learned

Despite the bitter experience, Nolte wasn’t done with business enterprises. He learned a lot in that endeavor and wanted to apply it to another.

So, in 2010, when he was filing the patent that would be the cornerstone for Animated Dynamics, he harkened back to his time with Chad Barden, who had been brought on as CEO of Quadraspec. “He had taken [another] small company to a successful exit with an acquisition to Intel,” Nolte said. “He was an inspirational guy and I studied him closely.”

Like many university researchers, Nolte never had formal business education or training. So he sought to fill his knowledge gaps.

In 2012, he attended a Purdue Research Foundation entrepreneurship boot camp. In 2013, he attended a boot camp put on by the National Science Foundation. That camp was key to learning how to win grants.

In 2015, he landed a $1 million NSF grant.

“At that point, we realized we weren’t playing around anymore, and this was going to become a real company,” Nolte said.

And he realized he still needed help.

“It was clear we needed to have people who were connected to large networks of key opinion leaders and investors,” he said. “As a faculty out of Purdue, I just didn’t have that.”

Nolte brought in Ted Schenberg and Travis Morgan, who were running a genotyping company, Strand Diagnostics, in Indianapolis. They were introduced through the Purdue Research Foundation.

“Animated Dynamics was a phenotyping organization, so it was a perfect match,” Nolte said.

The company grew to nine full-time employees before the pandemic. Now, it’s down to five, but Nolte is optimistic growth will resume when the pandemic abates.

“Due to the pandemic, clinical trials shut down and our whole model revolves around clinical trials,” he said.

‘This is important work’

Gaining business knowledge is just one of many challenges for academics wanting to start companies. Time is also an obstacle. Nolte said Purdue allows him to spend one day a week working on his company. He has no interest in walking away from his academic job. He still loves teaching.

But Nolte, who began as president at Animated Dynamics but now serves as chief scientific officer and owns 10% of the company, spends much of his own time on the company.

“Let’s just say I have a lot of strange hobbies,” he said. “The adrenaline keeps you running for years. I think this is important work, and that’s a big part of it. Even the challenges make it interesting. Trying to overcome those challenges is a reason to get out of bed in the morning.”

But he insists the venture is not a burden. And he’s not driven to keep grinding by a big financial payout.

“Scientists are motivated by different things,” he said. “We’re motivated by the challenge and the intellectual aspects of things. It would be great to make money, but I would have to say that was never one of the prime motivators.

“There’s a strong desire to make an impact—and not just for yourself. You do have a sense that you’re improving the world. I suppose all entrepreneurs say that. It sounds like a joke, but it’s also real.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.

It would be helpful for the reporter to be more specific about the campuses these scientist/entrepreneurs come from. Case in point: Prof. Ali Jafari is a professor in the School of Engineering and Technology at IUPUI here in Indianapolis. The article merely says IU, which is inaccurate. Prof. Jafari is tenured through Purdue University, but he is an employee of IU and IU got the money for his invention. Confused? Welcome to IUPUI! Your reporter can avoid inaccuracies by identifying the specific campus where the people work. For example, Prof. Zlotnik is at the Bloomington campus. Prof. Low is at Purdue’s West Lafayette campus.