Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA new report from the Indiana State Department of Agriculture shows that the state lost an estimated 350,000 acres of farmland over a 12-year period.

The Indiana General Assembly passed House Enrolled Act 1557 last year, tasking the ISDA to estimate the amount of farmland lost—as well as the cause of it—from 2010 to 2022.

“As a starting point, if you want to do something about it, you first have to know what reality is,” ISDA Director Don Lamb said. “So that was what the goal of this this was—to really come up with the reality of what the lost farmland has been.”

Lamb told Inside INdiana Business that while farmland acreage dropped nearly 2%, the findings of the Inventory of Lost Farmland weren’t totally surprising.

“It’s a significant number,” he said. “We knew the number would be significant. I don’t know that we expected it to be higher or lower. But it does tell us that there is something there that we need to keep an eye on.”

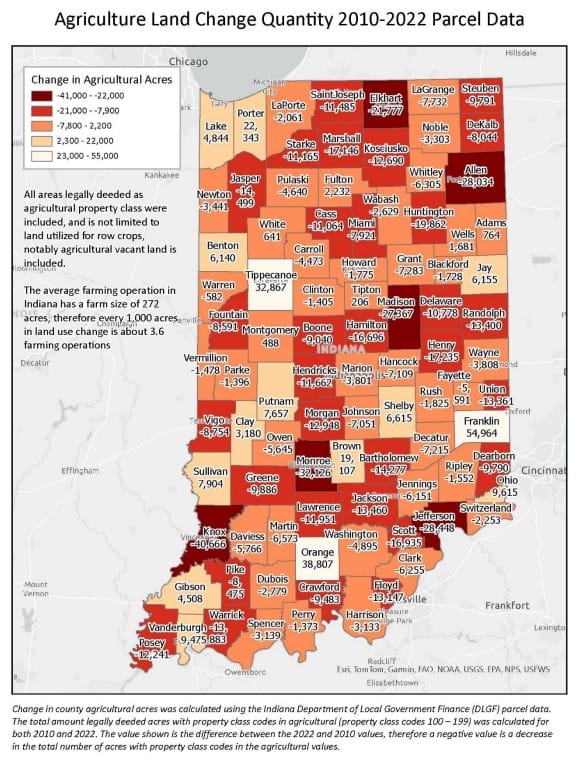

The ISDA gathered data from all 92 counties using two sources: parcel data from the Indiana Department of Local Government Finance and the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service Crop Data Layer.

The agency said both datasets have different qualities that make them desirable for attempting to discern both the quantity of land use change and the causes of that change.

The report found that agricultural land was most likely to be lost in areas around the edges of cities and suburban areas, and the primary cause of that loss was due to residential use.

“Part of it is the fact that businesses and manufacturing come in, and then you need workers to fill those jobs. And all that is a good thing,” Lamb said. “From our standpoint, we don’t want to look at it and say it’s bad to have economic development and growth; we just want to make sure that agriculture is preserved.”

The report found that Allen, Elkhart, Jefferson, Knox and Monroe counties saw the biggest drop in farmland over the 12-year period.

Lamb said that while land use should always be a local decision, he hopes the report will remind local governments to look at how future developments could potentially impact their local economy by taking away farmland.

“One thing that we would like to to do as agriculture is to make people aware that agriculture is not just a ground zero spot to develop on, that there is a lot of tax implications,” he said “There’s a lot of things going on that are good for an agricultural economy. And so when you bring in something else that’s an alternative to that agriculture, it’s not automatically going to bring more money into the county.”

But the ISDA report didn’t only bring negative news. Despite the loss in acreage, data found that Indiana’s production of cash crops increased. In 2012, the state produced over 597 million bushels of corn for grain and nearly 219 bushels of soybeans. Those numbers increased to over 1 million bushels of corn and over 326 million bushels of soybeans in 2022.

Lamb said that Indiana farmers are resilient and are good at producing more with less.

“That really comes down to genetics and all the different advances we’ve had in the last 12 years. It’s been pretty amazing the different things that are available to farmers and the technology,” he said. “Even though we’ve lost this much farmland, it doesn’t mean we’ve lost that much productivity.

Looking ahead, Lamb said the state now has a base of where it stands when it comes to available farmland. Now, the question is what does that mean for the future, and what should Indiana be concerned about?

The ISDA outlined several recommendations to the Legislative Council, the first of which is for the legislature to pass a bill directing the ISDA to update the Inventory of Lost Farmland every five years, starting in 2029.

The agency also wants to involve local units of government in the farmland preservation conversation since most land-use decisions are made at the local level.

“No two counties are the same and neither are their comprehensive plans, zoning ordinances or land use decisions,” the ISDA said. “Local units of government should be empowered to identify land use trends in their area and use all available information when making land use decisions.”

The ISDA is also encouraging local governments to be proactive rather than reactive when big development projects arise, noting that “communities should revisit their comprehensive plans and ensure they have a strategic vision for the future of their community including agriculture as a consideration.”

Additionally, the ISDA recommends tasking the state legislature to consider the threshold in which the lost number of farmland acreage significantly reduces access to food.

You can connect to the full analysis by clicking here.

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.

As some may recall, the summer of 2012 was blisteringly hot. There was a run of 100+ degree days and drought. Query: did those factors produce the dip in farm production?

Was this a case of ISDA selective use of data?