Latest Blogs

-

Kim and Todd Saxton: Go for the gold! But maybe not every time.

-

Q&A: What you need to know about the CDC’s new mask guidance

-

Carmel distiller turns hand sanitizer pivot into a community fundraising platform

-

Lebanon considering creating $13.7M in trails, green space for business park

-

Local senior-living complex more than doubles assisted-living units in $5M expansion

Third in a series of dispatches from the Big Apple. For reviews of "Fun Home," "An American in Paris," and "The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time," click here. For ""Something Rotten," "Fool for Love," and "First Daughter Suite," click here.

Hamilton

I can’t think of another Broadway show in my lifetime that has generated the kind of far-reaching buzz as “Hamilton” has.

And I’m happy to report that this remarkable production of a stunning show deserves all the attention it's getting.

The good-luck-getting-a-ticket hit tells the sweeping life story of Alexander Hamilton, from his arrival as an immigrant to the not-yet-United-States to his fateful run-in with Aaron Burr’s bullet.

The twist: Hamilton and his founding brothers and sisters are played by minority actors (except for King George, of course) and their vernacular is R&B and rap rather than “1776”-style show tunes. Think it's trivializing to present the fundamentals of our nation being determined by clever verbal battles between political rivals? Then perhaps you should reread your American history (I recommend “Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation” by Joseph J. Ellis as an accessible starting point).

There's usually some sort of cataclysmic damage when worlds collide. But when composer/lyricist/playwright/actor Lin-Manuel Miranda mashes hip-hop and rap with Broadway, the result is instructive rather than destructive, enlightening rather than embarrassing. One form isn't imposed on the other: Miranda marries them in a way that seems right and true and proves gloriously entertaining. The approach isn’t a gimmick—it’s a smart way to see history through fresh eyes.

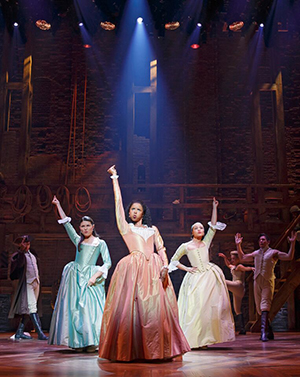

Credit Joan Marcus

Miranda and his all-star team have created a show that rocks and resonates, one that challenges and embraces, and one that left me thrilled at its expanded vision of what musical theater can achieve. Anyone surprised by the show’s reception doesn't get how hungry musical fans are to hear new voices from composers who know how to deliver theatrically, from Rodgers and Hammerstein to Leonard Bernstein to Stephen Sondheim. And when a show delivers song after song after song as compulsively listenable as Miranda has, it shows just how difficult and rare such an achievement is. That “Hamilton” has such crossover appeal is a kick in itself as it proves that musical theater songs and the stuff you hear on the radio don’t have to be mutually exclusive—as they’ve been the past 40 years or so.

In a sense, rapping Founding Fathers isn't inherently more anachronistic than the French student revolutionaries singing power ballads just a few theaters away. Or Prohibition-era Chicago murderesses singing and dancing to slinky 70s-era sounds. The beauty in "Hamilton" is how directly its contemporary sounds capture the spirit of its rebellious, anxious, verbose would-be revolutionaries. Rather than idiosyncratic, it feels right.

In the same way that hip-hop and rap draw on other musical forms, "Hamilton" creatively tributes its predecessors. When, early on, Hamilton sings about his determination to "not give away my shot" it serves as an exciting "I want" song, the kind of tune that traditionally anchors the opening of a musical but also doubles as foreshadowing of what will ultimately happen across the river in New Jersey.

I'm not versed enough to identify some of its rap roots, but I could clearly see, for instance, how "The Room Where It Happens," in which Aaron Burr's outsider status is underlined, demonstrates an awareness and respect for "Somewhere In a Tree," from Stephen Sondheim's "Pacific Overtures" score (a commercially less successful attempt at cultural groundbreaking from the 1970s). But knowledge of that show isn't required to get a joke. In fact, there isn't a joke to get. Miranda is both acknowledging and building from his musical influences in order to effectively tell the story he wants to tell. And while much of the creatively choreographed show is upbeat and kinetic, Miranda isn’t afraid to slow down the pace when needed, particularly in the achingly sad, beautiful, knowing "It's Quiet Uptown."

Credit Joan Marcus

“Hamilton” design esthetic is uncluttered. It doesn’t need to throw a chandelier at us or land a helicopter on stage. It captivates, instead, with a parade of memorable moments and characters speaking and singing in a way that draws us in and propels us forward.

There’s Anthony Ramos, as Hamilton's son, sharing his first efforts at written wordplay, and Daveed Diggs' Thomas Jefferson, caught up in the public character he has created for himself. Christopher Jackson subtly makes George Washington a man with the weight of a country on his mind while Okieriete Onaowan draws such distinct personas as Hercules Mulligan and James Madison that I had to double check my Playbill to make sure it was the same actor in both parts. Renee Elise Goldsberry’s acting chops shine as brightly as her voice as Hamilton’s sister-in-law Angelica. Enough can’t be said about Leslie Odom, Jr. as Aaron Burr, as indelibly intense a musical theater antagonist as Javert or Judas. And Phillipa Soo as Eliza Hamilton, not only helps create some of the most powerful emotional moments in the show, but well, I’ll just say that she and Miranda refuse to let Eliza become a footnoted, forgettable spouse.

“Hamilton” is radical in its approach but not in its messaging, its clarity, or its commitment to telling a good story. Yes, it covers crucial moments in American history (at one point, I had to smile at the realization that a packed house was transfixed on a song about the Federal Reserve system—take that, “Schoolhouse Rock”). But on a more universal level, it’s about being in the moment with limited information, knowing that your choices will affect the future. It’s about the conflict between your vision of yourself and the notion of compromise. It’s about how our humanity impacts history. It’s about legacy and who gets to tell your story.

And it’s about having a great time at the theater.

(And, no, I don't have a connection to help you get tickets so that you can be in the room where it happens.)

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.