Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowKeith Williams, a 45-year-old serial entrepreneur, said he knows that trying to be everything to everyone doesn’t usually bode well for businesses. But he believes the strategy will unlock success for the music tech startup he helped launch this spring.

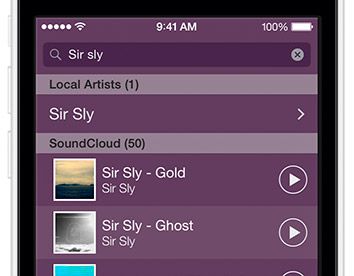

Williams is president of West Lafayette-based Caktus Music Inc., the company behind a smartphone application that seeks to be a home of sorts in a world where music consumption habits are widely disjointed and varied. The app allows access to content from multiple sources, including streaming services and personal music libraries, all integrated into one place.

It’s not just convenience the Caktus team is after. They want the consumer’s entire music experience—artist discovery, music consumption, concert ticket purchasing and more—to reside in Caktus’ app.

Williams

WilliamsThat might be a tall order. Scores of startups have ventured into the music space, industry experts said, and many have failed. At the crowded intersection of music and technology, ideas are abundant and solid business models rare. Even the most successful companies—including Pandora Media Inc. and its nearly 80 million active monthly users—have struggled to deliver profits.

“This is a promising area that they are delving into,” said Larry Miller, who runs the music entrepreneurship program at New York University’s Steinhardt School. But he noted that “the road to value creation in the digital music industry over the last 15 years is littered with the carcasses of dead companies.”

For better or for worse, the folks at Caktus have their blinders on. Co-founder Dane Regnier, 22, dropped out of Ball State University to focus on the app. He and his two business partners have done some bootstrapping and raised “a few hundred thousand” from about six investors, Williams said. None of them have a background in the music industry, but they’ve been traveling, networking and getting acquainted.

“From a businessperson’s standpoint, you always look and see these opportunities,” said Williams, who sold an ultrasonic instrumentation company to Tyco Electronics for seven figures last year.

“From a businessperson’s standpoint, you always look and see these opportunities,” said Williams, who sold an ultrasonic instrumentation company to Tyco Electronics for seven figures last year.

“And you wonder if you’re the person that can really catalyze that up to one of these billion-dollar [companies],” he said. “And what I saw here was that potential.”

Value proposition

Caktus looks to attract users on two fronts. First, they can listen to downloaded tracks they already own and full versions of streamed tunes they don’t—all without leaving the app.

Second, users can see who is listening to what on a map, a rare social interface in the world of media players. If something piques their interest, they can listen to a snippet and click a link to buy the full song in iTunes.

The streamed tracks in Caktus come through SoundCloud, the 175-million-user platform often called the YouTube of audio. Caktus has its sights set on music-streaming service giant Spotify, which has licensing agreements for its content and a far more comprehensive collection than SoundCloud. A partnership with Spotify is in the works, Caktus officials said.

“At this point, we’ve signed all the business documents,” Williams said, “and it’s winding through their legal departments.”

Under the tentative agreement, only paid Spotify subscribers would be able to access Spotify content on Caktus. Caktus could see growth from Spotify users seeking a united music platform, Caktus officials said, and Spotify could have another premium subscription driver. Spotify did not respond to requests for comment.

Revenue model

Today, Caktus gets paid every time someone buys a song or purchases concert tickets through the app. Officials wouldn’t disclose figures, but said it’s not a substantial amount. In the future, Caktus looks to facilitate artist merchandise sales and get a cut there, too.

But consumer revenue is only a slice of the pie, officials said. Once Caktus achieves a large user base, probably in the 50,000-user range, it intends to sell location and other user data to interested parties on a so-called freemium model. That means baseline data would be free, but broader analytics would come with a monthly price tag.

In an email, Caktus spokesman Joel Benson said, “We have seen interest in large venues using it for planning, marketing companies using it for targeted promotions, and a variety of businesses interested in our geolocation platform separate from the Caktus player.”

Getting to the subscription-revenue phase might take some time. Caktus has only 5,000 users and 19 active artists on the platform.

Crowded field

Caktus touts its social offerings, but numerous music apps have built-in sharing, voting, messaging and other social components. From a consolidation standpoint, an app called Soundwave allows users to play and share music from several sources, including YouTube.

Soundwave doesn’t have a map interface or SoundCloud integration, however, and it sends users to other apps to play certain songs.

Miller

MillerCaktus’ B2B-revenue ambitions also face stiff competition, experts said. Last month, Pandora launched an analytics tool that allows the roughly 125,000 musicians on its platform to access location and other data.

Miller said Caktus has a quality interface, but has the challenge of competing against other apps worldwide trying to solve similar problems.

Billy O’Connell, a professor of music-industry studies at Loyola University New Orleans, said the success of Caktus will depend on growing its user base. So user aggregation is critical, but he doesn’t think the app immediately compels people to drop their current habits in favor of Caktus.

“If I didn’t have the chance to put this in front of 44 kids, I don’t know that I’d be speaking with such certainty,” O’Connell said about his students. “And they kept saying, ‘Anything that makes this worthwhile, we already have.’”

Mark Montgomery, who runs Nashville, Tenn.-based entertainment firm FLO.CO, said he doubts the one-stop-shop approach can gain traction. People don’t mind going to venues or Ticketmaster for tickets, he said. And many of the problems Caktus is targeting, other companies with larger chops either are already addressing or have tried to.

“These guys, in my mind, have picked a very crowded space that has very little potential for exit,” he said.

Up next

Regnier

RegnierCaktus is the brainchild of Regnier, who dropped out of Ball State University last December and partnered with fellow student Chase Acton, who’s still enrolled at the school. Eventually, the two found themselves in front of Elevate Ventures, an Indiana-based venture capital group.

In January, Caktus was going through an Elevate Ventures program that involved a focus group and mentor advice. Williams was invited to serve as a mentor, but sought greater involvement when he encountered Caktus.

Caktus debuted at South By Southwest, an internationally renowned tech conference, in March.

The group participated in startup contests and has made inroads, at least primitively, with managers, record labels, and other players and institutions in the business.

With about six full-time employees and another nine or so contractors, most of their operations have been performed out of coffee shops. The group does plan to move into a new West Lafayette co-working space called the Anvil soon.

In addition to its Spotify ambitions, Caktus also has some updates it’s planning to roll out and some patents in the works.

O’Connell said the company’s immediate challenge is counteracting the ubiquity of the established competitors and adequately articulating what differentiates its product.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.