Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowMONTEZUMA—You’ve heard this fairy tale. The tiny school from the pencil-dot town on an Indiana map, clawing its way through the high school basketball tournament.

No, not Milan. The OTHER tiny school from the same season.

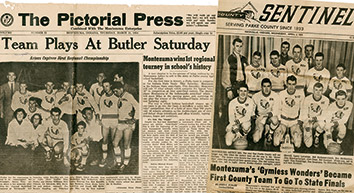

What a movie the Montezuma Aztecs would have made back in 1954. Senior class of 14, seven boys and seven girls. No place to play home games. The Gymless Wonders, people called them. They shared their practice area—60 feet by 27 feet—in the school basement with the band and a home economics class, and couldn’t put much air under their shots because of the low ceiling. The coach’s wife had to wash the uniforms, hanging them on her clothesline to dry.

What a movie the Montezuma Aztecs would have made back in 1954. Senior class of 14, seven boys and seven girls. No place to play home games. The Gymless Wonders, people called them. They shared their practice area—60 feet by 27 feet—in the school basement with the band and a home economics class, and couldn’t put much air under their shots because of the low ceiling. The coach’s wife had to wash the uniforms, hanging them on her clothesline to dry.

But they were good. They took a 23-5 record and marched to the semistate in Butler Fieldhouse, which to them looked like the Emerald City from “The Wizard of Oz.” Yes, on this 30th anniversary of the release of “Hoosiers,” we have come to say the movie could have been about them. If only they had not run into the

bully big school that knocked them out.

If only they had not run into Milan.

“They always talk about Milan being the smallest school. They really weren’t the smallest school,” said Ron Baumann, one of the Montezuma players. We’ll meet him in a minute.

On March 13, 1954, a school with 162 kids played against a school with 78. There has never been a semistate game quite like it, before or since. And while the victors became folk heroes, and the stuff of Hollywood, the losers went back home to their railroad town on the banks of the Wabash in western Indiana. A footnote to the Milan miracle.

You’ve heard of Bobby Plump? Well, he’s heard of Montezuma.

“It was a tough game, I can tell you that,” said the main man from Milan. “It was one of the few times we were the big school on the court. As I look back, Montezuma gave us our closest game before Muncie Central.”

The record will show that, while Milan was able to dispatch such bigger fish as Terre Haute Gerstmeyer and Crispus Attucks with Oscar Robertson, it was Montezuma that gave the glory-bound Indians their biggest scare, before the famous state championship game. It ended 44-34, but was only 32-30 going into the fourth quarter, and Montezuma was right there on the brink. The ultimate underdog being chased by an even more ultimate underdog.

“They were the only team we didn’t have a great scouting report on,” said Gene White, Milan’s center. “I understood from another source that in the regional, they weren’t expected to win but they did, so our scout may not have scouted the correct team.

“The most famous quote in Milan that week was, ‘We took the roar out of Aurora [in the regional] and we’ll take the zoom out of Montezuma.’”

Oh, yes, the Milan guys remember Montezuma. So shouldn’t we?

Which takes us to Parke County, seven miles west of Rockville, and the town with one blinking light. The old theater and hotels and cafe are all closed now, and the main drag, Washington Street, is mostly vacant windows. The purple paint on the water tower—school colors of the old Aztecs—is faded. The town that was 1,300 in 1954 has settled back to just over a thousand. The high school is long gone, consolidated into Riverton Parke, which at last count had won six games in three seasons.

North on Washington Street is a house with a sign on the driveway: “Entering Baumannville. Pop: 2. Ron Baumann mayor.”

They knew him as Ronnie Baumann in 1954, one of the leading scorers of the Aztecs. The basketball hero who left for the Navy not two months after that day in Butler Fieldhouse, and would eventually come back home to work at the Newport Chemical Depot, the only place in America that produced the VX nerve agent. He lives there still, with Linda, his wife of 60 years, not more than a mile from where he once played.

“Though it’s been 61 years, it’s kind of a family joke that, around March, somebody calls about the 1954 season. You’re early,” he said, sitting at his kitchen table in late January. “For our 15 minutes of fame, it’s went on for quite a while.”

Baumann can show you artifacts of ’54. Newspaper clippings, programs, the tattered net he cut down after the regional so long ago. The Montezuma letter jacket he can still get into, the one he got to wear barely a month before heading for the Navy.

He can tell you what it was like practicing in that basement. “You didn’t take any arched shots because they had steam pipes up there. Out of bounds was the brick wall, no padding, so when you went out of bounds, you knew it.”

He can tell you the awe that struck the Aztecs when they first walked into Butler Fieldhouse.

“If they had took the whole town, we couldn’t have filled up the section for Montezuma,” chipped in Linda. “The whole town did go. The only one left here, they always said, was the town cop.”

He can tell you about that Saturday morning, riding to Indianapolis with a caravan of 80 cars behind them, going through Rockville and finding people out on the streets clapping as they rode past.

And he can tell you about the game. Montezuma wore purple, Milan wore white. Milan built a big early lead, but when Montezuma cut it to two going into the fourth quarter, the Aztecs had all the momentum. Then the Indians went to their ball control they made so famous, and that was that.

“I remember I couldn’t shoot the basketball very well (2-for-13, in fact). They could hold it as long as they wanted to. I think we probably messed up not pressing them more, going out and making them dribble or something. We really thought we could have beat them. It’s like any game. Some nights they go in, some nights they don’t.”

And when it was over?

“We went out to some fancy restaurant and had a meal, and then we came home.”

He can tell you what time has done, showing you a photo of the team, filled with boys of six decades ago. “He’s passed away … and he’s passed away … and he’s passed away …”

Five of the 10 are still living, including four of the starters. One is center Vic Edwards, who Baumann said prayed before every free throw. “The prayers weren’t answered all the time.” Another is guard Dick Pitman, who had the team’s best jump shot.

Pitman splits his time between Florida and Indianapolis now, a man married for 45 years who has endured a stroke, quadruple bypass surgery, and a valve replacement that kept him in the hospital more than three months.

Back then, everyone in Montezuma knew everyone else, of course.

“And you knew how many dogs everybody had, too,” Pitman said. And everyone knew how the boys felt about basketball.

“My dad put up a plywood [backboard] and he made a ring and welded it together,” Pitman said. “He went to Montgomery Ward for a net, and I taped it up on a thorn tree. We never dreamed of going to the semistate at that point. But we loved it so much. In the winter time, we’d shovel off the snow and play. That’s dedication. I don’t think boys would do that today.”

He returned to Butler the next weekend after the semistate to see Milan complete the dream, and was sitting under the basket with his mother when Plump’s shot went through.

Pitman gets back to Montezuma for reunions. But Baumann is the one who’s stayed, the most visible link to one incredible spring. He can tell you that the memory of 1954 is fading in his town, like the paint on the water tower.

“The people that really remember, they’re nearly all gone now. We had one friend in church, she’d say, ‘I always remember that basket you made over at Greencastle [to win the regional].’ She’s passed away, but a couple of months ago, her son was in town and I was talking to him and mentioned to him that every time I’d see his mother, she’d mention the basket I made. He said, ‘I’ve heard that story about 60 times.’”

One other thing Ronnie Baumann can tell you. He has the tape of “Hoosiers” and has watched it many times. Surely, there had to be gnawing moments of wondering … what if? Hickory could have been Montezuma.

“It’s a very small part, really it is. When you only have 33 boys in school, we were lucky to get where we were. But being envious, that’s not part of it. Milan played the game and they won and that’s the way it should be. They deserved everything they’ve got.”

Here’s the ironic part. If 21st century Montezuma has forgotten what its native sons once did, the state champions of 1954 have not. They understand what a unique stage they shared, and how close it had been.

“One time, we were going west, my wife and I,” Milan’s White said, “and we took the road that went through Montezuma, just so I could see it.”

And Ron Baumann? He has never been back to Butler Fieldhouse since 1954.•

__________

Lopresti is a lifelong resident of Richmond and a graduate of Ball State University. He was a columnist for USA Today and Gannett newspapers for 31 years; he covered 34 Final Fours, 30 Super Bowls, 32 World Series and 16 Olympics. His column appears weekly. He can be reached at [email protected].

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.