Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn a laboratory on the third floor of the Indiana Biosciences Research Institute, researcher Marco Tjioe is squirting liquid into a vial to get a chemical reaction. The next step: Drain off the excess liquid and examine the mixture.

“That leaves us pure antibodies,” said Tjioe, a postdoctoral fellow, one of 27 researchers in labs around the building working on experiments to gain new understandings and treatments for diseases ravaging Indiana, such as diabetes, obesity and other metabolic disorders.

Down the hall, in other labs, scientists are busy with chemical reactors, imaging systems and other analytical equipment. Much of the work is basic science, trying to unlock new molecular information on how cells work, regenerate and fight disease.

Down the hall, in other labs, scientists are busy with chemical reactors, imaging systems and other analytical equipment. Much of the work is basic science, trying to unlock new molecular information on how cells work, regenerate and fight disease.

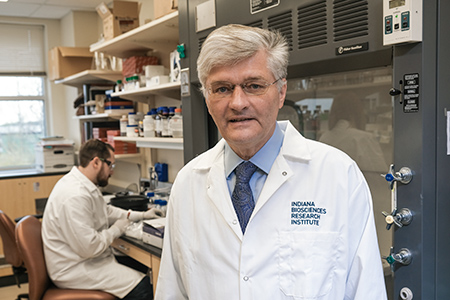

“We try to isolate the genetic information, amplify, characterize it,” said top official Rainer Fischer, senior executive for innovation and discovery. “Our imaging systems can go all the way down to the single cell.”It’s a busy time at the IBRI, an independent group set up six years ago to help bridge the gap between Indiana’s research universities and industry in life sciences.

Backed by more than $100 million in funding from Indiana companies and foundations, the institute has equipped two floors of laboratories and offices at the Indiana University Biotechnology Research & Training Center on West 16th Street.

It has hired 39 employees and hopes to ramp up to 80 within another three years.

The goal, as the IBRI puts it, is to “eliminate barriers and foster team science” with other scientific organizations around Indiana—including Eli Lilly and Co., Cook Medical, Roche Diagnostics and research universities.

All the activity marks a turning point for the center, which has maintained a fairly low profile since launching in 2013. Last year, officials said, the institute significantly expanded its research capabilities and broadened its collaborations.

Around the building, researchers work on a variety of projects, such as identifying molecular pathways that could be manipulated to preserve beta cells, which produce insulin and help regulate the amount of glucose in the blood. On many of the projects, there’s a heavy emphasis on diabetes, obesity and nutrition, which the institute and its partners have identified as major health concerns in Indiana.

IBRI officials declined to talk about specific research projects, citing confidentiality with outside partners. And they did not disclose how many contracts they have won or revenue generated. But they say the number of projects is growing across a variety of research areas, and that they are working hard to attract additional funding to tackle even more research.

Changes, challenges

Still, the institute has some challenges on its hands. Fischer, who was hired in April 2017 as chief scientific officer and was promoted six months later to CEO, announced last month he was stepping down from both roles for health reasons.

Fischer, 60, who has diabetes, said he wanted a less-demanding role, and now will oversee innovation and discovery while the institute looks for a new CEO. He will also continue to attract new partners for sponsored and contract research, and new donors and grant-makers.

Evans

EvansIf the change in leadership was a glitch for the IBRI, top officials did not let on, and said they don’t expect to skip a beat.

“We have initiated a search to find a CEO who will support Dr. Fischer and the entire IBRI team with the leadership, vision and capabilities necessary to maintain our growth,” former Indiana University Health CEO Dan Evans, chairman of the IBRI’s board, said in a statement. “During this time, we expect to conduct business as usual with no disruptions in research or operations.”

Even so, the change comes at a big moment.

Next year, the IBRI will move a few blocks east into 16 Tech, a planned 60-acre, tech-focused live/work community that will transform the aging West 16th Street business corridor. The campus will combine office space, research labs and incubators with retail, apartments, green space and walking trails.

The IBRI will anchor the first building, set to open in summer 2020.

It’s a major step that could give the institute even more visibility. That’s a big goal of the young organization, which is still relatively unknown outside research circles. If the IBRI is to make a bigger mark, it will have to produce some remarkable research, Fischer acknowledged.

“We need to have big stories, big success stories,” he said.

One possibility, he said: developing an antibody that could be used to treat diabetes with fewer complications. Another example: coming up with a “well-being app” that combines health information from a patient’s electronic medical records with nutritional and activity information to help the patient learn how to keep glucose levels on an even keel.

Yet another: helping agricultural partners, such as Corteva Bioscience (the agricultural spinoff of DowDupont, with a large research campus on Indianapolis’ northwest side) develop crops that are natural healers and help lower blood glucose.

Staying organized

Under its roof, the institute has set up four centers to streamline its research and generate those types of reputation-making breakthroughs: the IBRI Diabetes Center, which focuses on the molecular basis of diabetes and its complications; the Applied Data Sciences Center, which analyzes vast amounts of health data to help identify and predict diseases; the Pharmaceutical Biotechnology Center, which develops and makes antibodies and vaccines; and the Single Cell Analytics Center, which analyzes cells to help diagnose infections and other diseases.

That might seem like a lot of organization-building, but officials say it’s necessary to keep all the research organized and pulling in the same direction.

Already, the institute has figured prominently in a large data study of Type 2 diabetes that was published in January in the journal Nature Medicine. The IBRI’s role was to provide and help analyze data—which originated from 100,000 diabetic patients—that it obtained from the Indiana Network of Patient Care database. Using that data, researchers at partner Roche Diagnostics were able to confirm findings of an earlier study and do additional research in predicting patients at high risk for developing chronic kidney disease.

Harrison

HarrisonWhat the IBRI did was help turn an indecipherable mountain of data into an understandable set of figures. The problem was that all the data had been collected in a non-standardized fashion, Fischer said, making it almost impossible to make any correlations or draw any conclusions. The IBRI worked with the Regenstrief Institute, Roche and Lilly to clean up the data.

“I think this is the perfect example of what IBRI hopefully can do more in the future,” Fischer said, “to connect and bring together these partners from different disciplines to deal with these data and draw some conclusions.”

Even in the early days, the IBRI is generating praise from some of its partners for how strategically it has identified its research priorities, and how it has methodically gone about hiring staff, getting equipment and building momentum.

“We’re a big cheerleader for IBRI and have been forever,” said Marietta Harrison, special adviser for strategic initiatives for Purdue University’s research and partnerships. “We have three projects with the IBRI, we host IBRI scientists, and we want to grow that relationship.”

Schacht

SchachtAaron Schacht, executive vice president for innovation, regulatory and business development at Elanco, the Greenfield-based maker of animal medicines, called the IBRI an important initiative that could help Indiana “advance key areas of science.”

Dr. Kristina Box, Indiana’s health commissioner and a member of the IBRI board, said she was impressed with how the institute has worked closely with partners in industry and universities on research that could promote public health. But for an organization that is going through a growth spurt, she said, growing pains are likely.

“From my perspective, the IBRI’s biggest challenges are in seeking new sources of grants and funding, and attracting the talent needed to support its growing research,” Box said.

Chasing funding

No question, raising money—through grants, research contracts and other sources—is a constant effort for the young institute.

Box

BoxIt was launched as a statewide public-private partnership with an initial $25 million state commitment and philanthropic funders. Executives from Eli Lilly and Co., Roche Diagnostics, Dow AgroSciences, Indiana University Health, Cook Medical and Biomet have supported the effort, and many serve on its board.

Three years ago, the IBRI scored a huge win when two major institutions announced they would donate a total of $100 million. The Lilly Endowment, one of the nation’s largest private philanthropic foundations, donated $80 million and the Lilly Foundation, an arm of the Indianapolis-based drugmaker, donated $20 million.

Last year, in a continuing show of support, the institute won an additional $5 million from the Lilly Foundation.

Also last year, the Indiana State Budget Committee gave the IBRI’s comprehensive plan its blessing, a move that will allow it to request $20 million from the Indiana Economic Development Corp. once it hits certain milestones.

The institute is focusing on a range of diseases, including diabetes and other metabolic disorders. It also aims to gain new insights by analyzing data. (IBJ photo/Eric Learned)

The institute is focusing on a range of diseases, including diabetes and other metabolic disorders. It also aims to gain new insights by analyzing data. (IBJ photo/Eric Learned)All told, the IBRI had an endowment of $111.6 million at the end of 2018.

Meanwhile, it is trying to win more research contracts from corporate and academic partners to make sure it can pay for operations without eating into its endowment. Last year, the institute spent $1.2 million on capital expenses and $9 million on operations. It did not disclose how much it raised through research contracts.

“In terms of revenues, you can always do better,” Fischer said. “I think, overall, we are pretty much on track, from what we have predicted and what we have in mind so far.”

And if Fischer’s track record is any guide, the IBRI could raise many millions of dollars a year in research contracts and hire scores of researchers.

For nearly 20 years, in his previous role as senior executive director of the Fraunhofer Institute for Molecular Biology and Applied Ecology in Germany, Fischer established collaborations in more than 25 countries, and raised almost 1 billion euros in research funding.

His role was top scientist at the organization’s molecular biology and applied ecology institute, which specialized in applied research into pharmaceuticals, plant technology, genomics, immunotherapy and other hot topics.

Fischer boosted the institute from 40 to 680 employees. Working with industry, his team served up some eye-catching technologies. One collaboration, with tiremaker Continental AG, explored how dandelions could be used as an alternative source of rubber. Another project studied how antibodies can be produced by genetically modified tobacco plants to treat a wide range of diseases.

So far, the IBRI is on track to hit many of its targets, Fischer said. And he pledged to continue to look for ways to bring in more business, build more partnerships and help build a thriving life sciences landscape here.

“At Fraunhofer, it took me close to 20 years to go from 40 to almost 700 people,” Fischer said. “Who knows what can happen in 20 years here?”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.